Art World

Art Bites: Monet Had an Appetite for Destruction (of His Own Paintings)

The Impressionist may have wrecked up to 500 "unsatisfactory" canvases.

These days, the worst threat that Claude Monet’s canvases are liable to face is being targeted by climate activists with mashed potatoes or soup, as well as burning in the occasional house fire, but that’s another story.

In the Impressionist’s own day the paintings faced a worse danger: Monet himself. Dissatisfied with his paintings, he took knives and his own boots to them rather than send them to hotly anticipated Paris exhibitions, including one scheduled for 1907, which didn’t happen until 1909 for this very reason.

Monet isn’t the only historic figure who has been guilty of attacking their own work. Artists from Michelangelo to John Baldessari, Agnes Martin to Gerhard Richter, have been prone to destruction as well as creation, each for their own reasons.

Others have used legal means or social media campaigns to try to achieve the same purpose: Cady Noland disowned a work after learning that parts had been replaced, and Richard Prince disavowed one that he sold to Ivanka Trump.

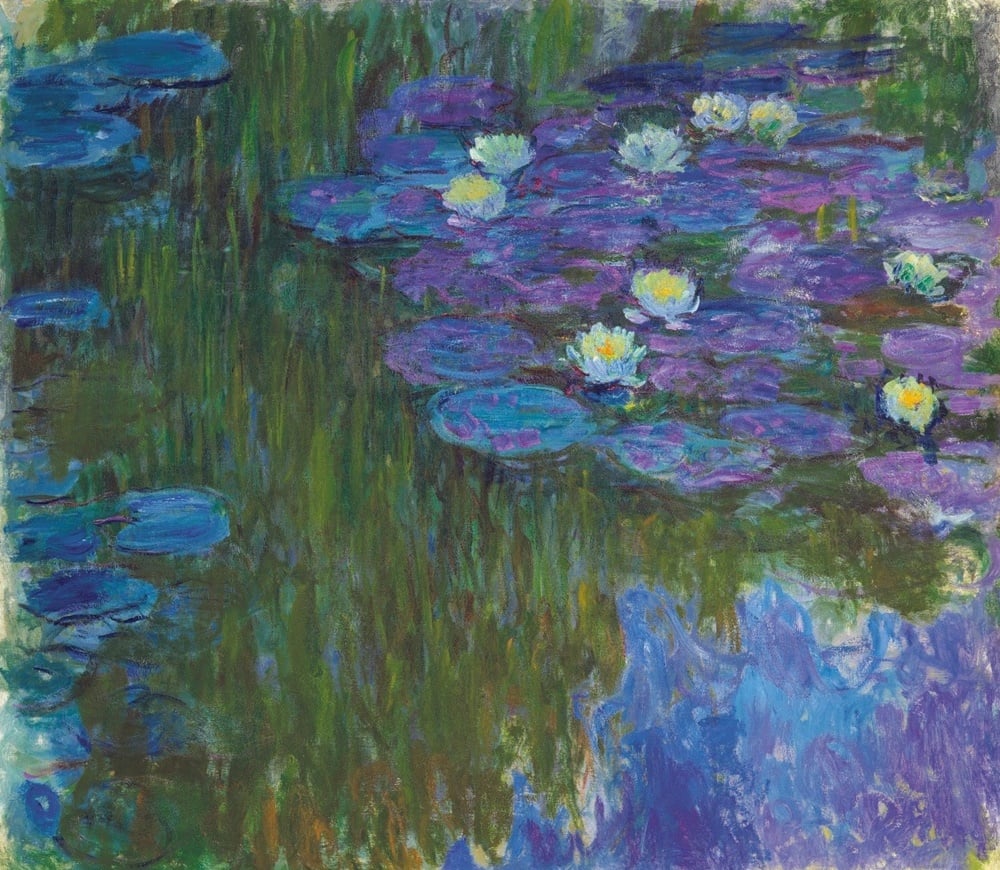

The Water Lilies by Claude Monet at Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris. Photo courtesy of the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris.

Sotheby’s estimates that Monet may have wrecked as many as 500 canvases. One newspaper account from 1908 said that he destroyed 15 in that year alone and put their value at $100,000, which, accounting solely for inflation, would equal $3.4 million today.

Of course, his paintings have skyrocketed in value since then, so the real equivalent is incalculable. Considering that incredible rise in value and renown, it’s ironic to read his own words: “My life has been nothing but a failure, and all that’s left for me to do is to destroy my paintings before I disappear,” he once said.

Those around him suffered as a result of his own unhappiness. “He punctures canvases every day,” his wife Alice wrote to a friend in 1908. “It is truly distressing. One day, things are not too bad; the next day all is lost.”

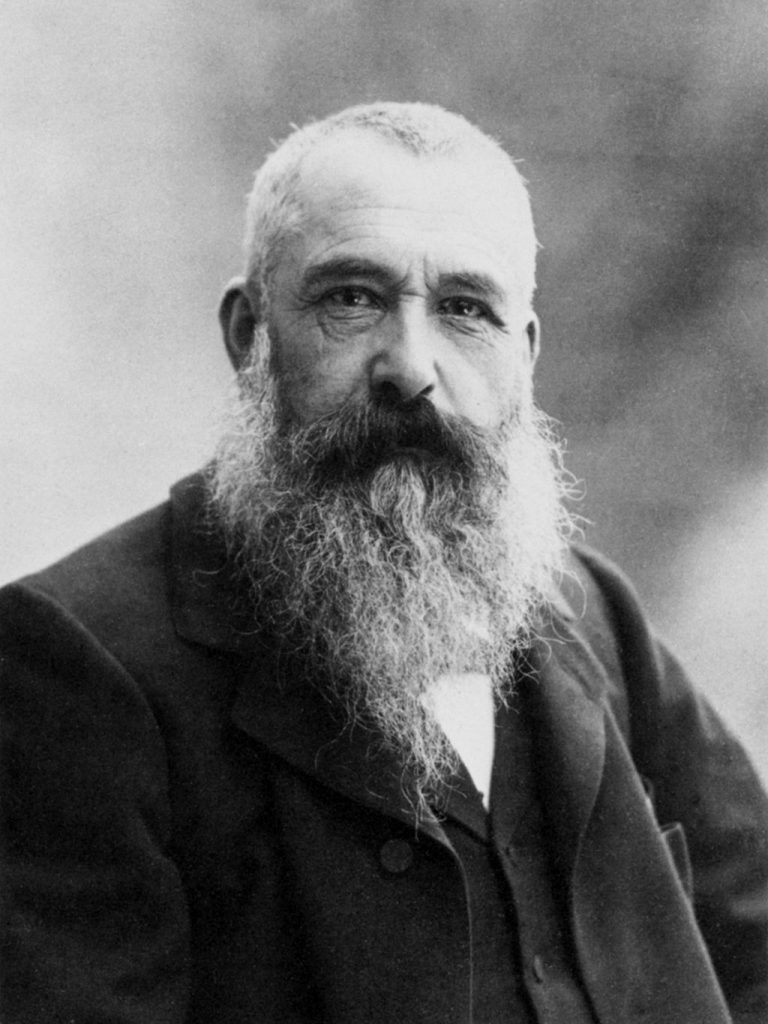

Claude Monet, 1899. Photograph by Nadar, courtesy of Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images.

After creating a famous garden full of Japanese-style foot bridges over ponds full of water lilies, he endeavored to recreate its beauty on canvas, to his stark dissatisfaction. In 1908, the same year he reportedly mangled those 15 paintings, the 68-year-old artist, who was looking back over his career, wrote to a friend: “These landscapes of water and reflections have become an obsession. It is beyond my powers as an old man, and yet I want to arrive at rendering what I feel… [I] hope that after so many efforts, something will come out.”

The water lily paintings that left Monet’s studio unharmed have come to hang on museum walls throughout the world, and are market mainstays. His 1914–17 canvas Nymphéas en fleur (Water Lilies in Bloom) sold for some $84.6 million at Christie’s New York in 2018, becoming his priciest painting on the subject.

Claude Monet, Nymphéas en fleur (c. 1914–17). Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

Former French prime minister Georges Clemenceau, who was close with the painter, told a journalist after his death that “Monet would attack his canvases when he was angry. And his anger was born of a dissatisfaction with his work. He was his own greatest critic.”

Only the grave, the artist said, would save him from his discontent. “When I am dead,” he told Clemenceau, “I shall find their imperfections more bearable.”

Of course, without seeing the destroyed paintings, it is easy to speculate that they were of the highest quality and that it was only pique that sent them to the trash bin. But at least one contemporary observer approved of the artist enforcing his own high standards, telling the New York Times, “It is a pity, perhaps, that some other painters do not do the same.”

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.