Art World

Looking to Turn a New Page? Here Are 17 Incredible Art Books to Read That Will Open Up New Horizons for Your Mind Under Lockdown

Now is as good a time as any to read a few classics.

Now is as good a time as any to read a few classics.

Artnet News

Is the barrage of bad news getting you down? Are you looking for an escape from the news cycle? Perhaps it’s a good time to do a little catchup reading. We canvassed our editors and staff writers for their picks of what to read while under lockdown. We’ve got everything from historical fiction to true crime, which should be more than enough to keep you busy.

Read on for our picks below.

This is a beautiful brick of a book. It’s got 88 color illustrations of Judd and Judd works—but honestly it’s perfect for being stuck at home and away from the real thing, giving you thorough interviews with the artist from the early 1960s up to the early ’90s, painting a loose-limbed and irascible picture of the artist known for his gleaming perfectionism.

—Ben Davis

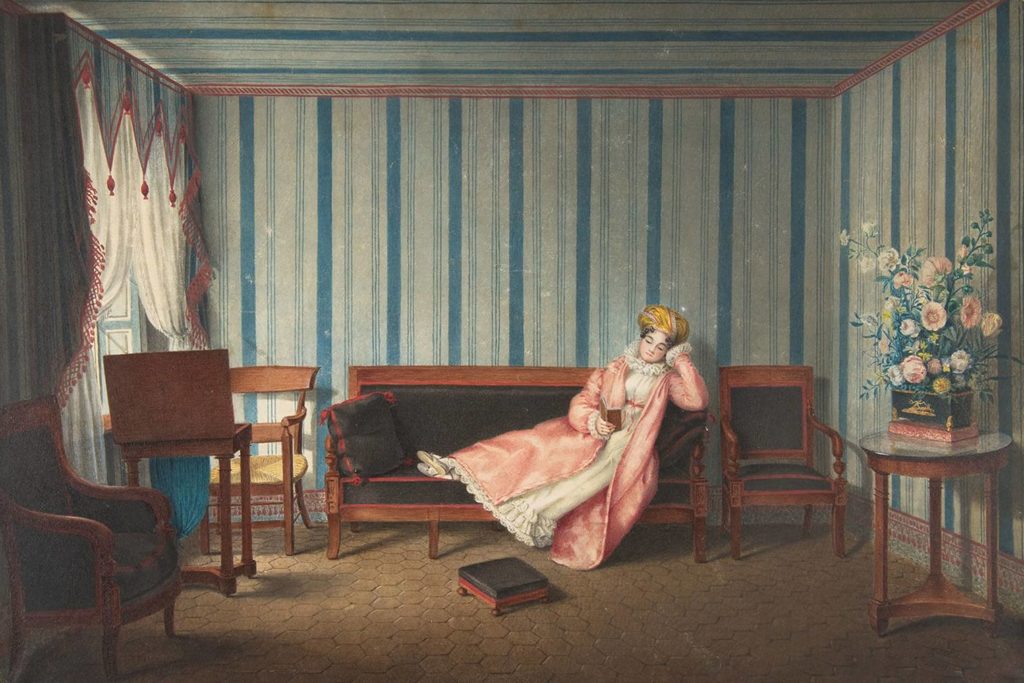

There’s a knowing provocation in the title of this acclaimed book, but there shouldn’t be. This unjustified yet underappreciated tension is the starting point in multidisciplinary artist and writer Jenny Odell’s argument for reprioritizing our own value as individuals rather than ever-spinning cogs in various machines. How to Do Nothing targets technology, the attention economy, and hyper-aggressive capitalism for slowly but surely sawing away our connections to almost anything but quantifiable output in all its forms, from professional labor, to social-media activity, to the “side hustles” we’re all supposed to be running to get what we really want. Often using thematically linked artworks to illustrate her points, Odell presents an alternative solution for fulfillment and (relative) peace, one that reframes self-care as the cultivation of our relationships to ourselves, our communities, and our ecology rather than as consumption-based self-indulgence (that we should also probably be Instagramming). I can’t imagine a more opportune moment to consider those concepts than now.

—Tim Schneider

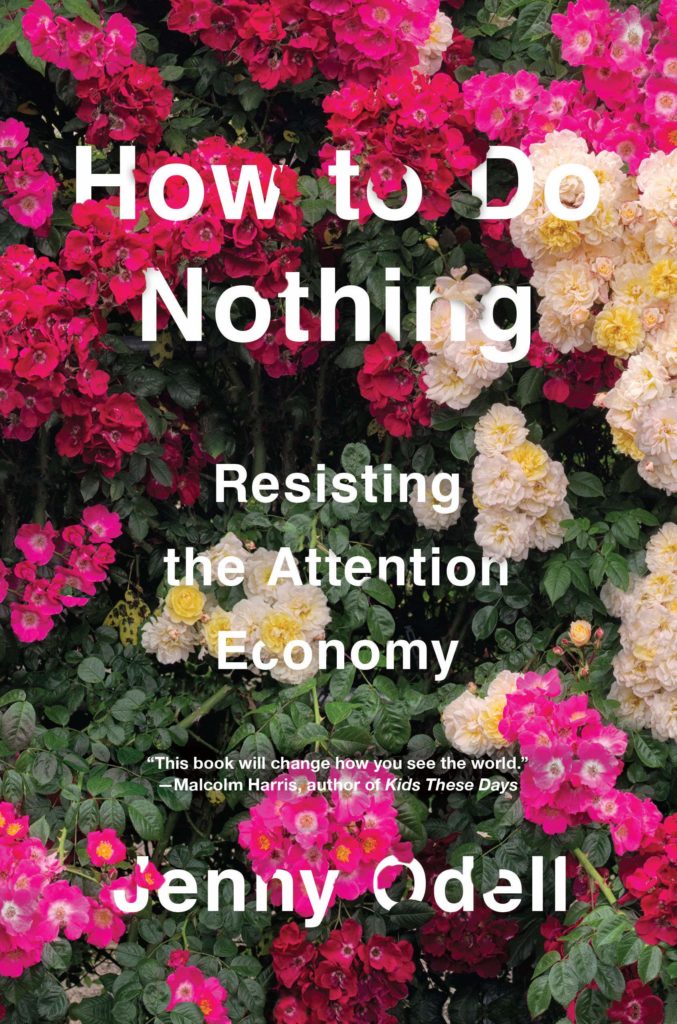

Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X by Deborah Davis. Courtesy of Tarcher.

Before there were the Kardashians or Paris Hilton, there was Virginie Amelie Gautreau of New Orleans, who became a Paris “It-Girl” in the 1880s. Having her portrait painted by up-and-coming painter John Singer Sargent for the 1884 Paris Salon should have cemented the 23-year-old’s place in the upper crust. But instead, it unfairly destroyed her reputation beyond repair. The scandal came down to one seemingly innocuous detail: the strap of her dress dangling off her shoulder suggested a sexual encounter, and was met with public outcries of indecency. A chastened Sargent repainted the strap firmly in place, and the painting was rechristened Madame X. Deborah Davis’s account of the ill-fated work’s creation reveals that Gautreau was a fascinating figure in her own right, and in many ways ahead of her time.

—Sarah Cascone

The central question in Canadian author Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel is whether art can save us. A unseasonably strong flu pandemic has ravaged the world population, leading to waves of death and chaos. The internet is unplugged, running water and electricity are no more, and governing bodies no longer exist. A wandering troupe of musicians, actors, and performers remains on a sparsely populated planet. These lovers of the arts travel through a surprisingly enchanting post-apocalyptic landscape performing crowd-pleasing Shakespeare plays before ending up at the Museum of Civilization, a defunct airport that serves as a wunderkammer of items from the old world, like cellphones and high heels. Despite the grim backdrop, it’s fun and optimistic, the plot is driving, and the writing is suspenseful and erudite. What is the place of metaphor, poetry, and art in end times? The answer lies in the troupe’s motto: “survival is insufficient.”

—Kate Brown

When the architect of the famous Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Expo urgently needed a fountain as a foil to Picasso’s Guernica, he turned to Alexander Calder—and the US artist rose to the challenge. Jed Perl’s masterful biography of the young artist tells of how he created his Mercury Fountain at double-quick speed as a beguiling piece of agit-prop Modernism to champion the Republican cause and raise money for child refugees. Back home in Roxbury, Connecticut, Calder created an array of humble gadgets, including a toilet-paper holder shaped like a hand, an ingenious electric toaster, and even a strainer hair trap. And he crafted them all with the same panache as his breakthrough piece of public art.

—Javier Pes

The Goldfinch has been out forever, but if you’ve never worked your way through its 700 pages before, now may be a good time. (And even if you’ve been there, done that, it might be worth revisiting to compare it with the movie version starring Nicole Kidman, which came out last year.) The story begins with a bombing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the somewhat accidental theft of an Old Master painting, and it doesn’t get any less dramatic from there. Like a late-night Netflix-binge, it will keep you up as you go on a rollercoaster ride involving a slew of double-dealing, drugs, and an underground network of deadly criminals. Although the painting, Carel Fabritius’s The Goldfinch, drives the plot, the book is ultimately a coming-of-age story centered on its sensitive protagonist, Theo.

—Naomi Rea

The Black Death that gripped Europe between 1347 and 1351 was a calamity on an unimaginable scale. The plague killed perhaps 60 percent of the continent’s population; was attended to by widespread economic collapse, notably of the major Florentine banking institutions; and inaugurated a cultural reckoning that extended well into the Renaissance. No one has done a better job of explaining how the Black Death worked its way into Florentine and Sienese culture than the scholar Millard Meiss, whose study on the subject remains an art-historical classic.

—Pac Pobric

Anne Rice, Cry to Heaven

Anne Rice, Cry to HeavenI don’t know about you, but my reading comprehension and standards have largely gone out the window. So may I recommend the literary equivalent of mashed potatoes? Cry to Heaven, unlike other works by the queen of vampire fiction, Anne Rice, forgoes the supernatural in favor of bawdy historical fiction. Set in 18th-century Italy, it focuses on the plight of castrati opera singers and the occasional court painter, and it’s got some light political intrigue, musings about the role of beauty in art, bodice-ripping romance, and a mysterious family secret that involves a creepy oil painting. If you want to lose yourself in an art world very unlike our own, look no further.

—Tatiana Berg

There are plenty of explainer-y books on why rich people spend exorbitant sums of money on paintings and sculptures. This is not that book. Instead, it’s a series of lived-in anecdotes, a gossipy, rip-roaring compendium of late nights with Soho-dwelling minimalists who created a new visual aesthetic and the drink-swilling Upper East Side doyennes who supported them, along with mini-profiles of dealers who emerge as the power-wielding gatekeepers. All the characters come vividly alive as they create a new reality on the streets of Chelsea in the midst of the birth of a global arts district rendered in technicolor. And when we all come back from quarantine, there’s a good chance this world will be wiped off the face of the earth, so might as well absorb its memory before it slips away forever.

—Nate Freeman

A few years ago, the late critic and professor Maurice Berger curated an excellent exhibition at the Jewish Museum titled “Revolution of the Eye: Modern Art and the Birth of American Television.” And although it’s hard to believe now, there was a time when TV was experimental. Even MoMA had a “Television Project” in the 1950s, using the new mode of communication as a way to bring art to the masses. Berger’s work shines a light on some of the artists and designers who influenced the medium’s early aesthetics (and in some cases, used it as a way to promote their work), including Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp, Roy Lichtenstein, Man Ray, Saul Bass, Ben Shahn, and Andy Warhol. There’s also an online version of the exhibition that includes works and clips from the show. As our 24-hour cycle churns into overdrive, now is as good a time as ever to explore art’s impact on the way we get our news.

—Katie Rothstein

Japanese-born, English author Kazuo Ishiguro is a master of subtle, patient writing. His grand gestures come in the form of characters’ small utterances, which slowly work to unravel the outward appearance of things. An Artist of the Floating World is no exception. Here, Ishiguro tells the story of Masuji Ono, an aging artist in post-war Japan who is in the midst of protracted marriage arrangements for his youngest daughter, Noriko. A bohemian painter of Japan’s “floating world” nightlife and revelry in his youth, Ono abandoned these pursuits to become a propagandist for Japanese Imperialism. Now, years later, in the midst of American occupation of the island and with Ono’s wife and son dead, the artist reflects on how idealism and ambition can ultimately be so misguided—and how art can powerfully shape culture. As with Ishiguro’s masterpiece (and a favorite of mine), The Remains of the Day, we’re privy to the complex mind of a character who has been left behind by changing cultural mores, but who nevertheless strives to understand and accept himself while acknowledging that there is no undoing the past.

—Katie White

In this publication, the work of groundbreaking photographer Dorothea Lange work is presented in diverse contexts, ranging from photobooks, Depression-era government reports, newspapers, magazines, and poems, alongside writings by contemporary artists, writers and thinkers. Along with an essay by Sarah Hermanson Meister, the book also includes texts by Sally Mann, Wendy Red Star, and Rebecca Solnit.

—Eileen Kinsella

These are strange, strange days, and if you feel like a bit of a mess, this story of a misunderstood artistic genius is just what you seek. George Ohr, the self-proclaimed “mad potter” of Biloxi, is now considered a peerless sculptor who pushed the boundaries of the medium to an extreme. I’ve been wanting to take up pottery for a long time now, and just as I was about to sign up for classes (I was so close, I swear) the quarantine measures have thwarted my plans. Luckily, the gorgeous photographs of twisted clay Ohr kneaded and coaxed into impossibly thin-walled vessels is a perfect antidote to my malaise.

—Caroline Goldstein

Former FBI agent Robert K. Wittman, who founded the agency’s Art Crime Team, offers this riveting memoir about infiltrating the shadowy art underworld to help track down stolen works of art. His undercover work led to several notable success stories, including the recovery of a Rembrandt van Rijn self-portrait. To hear Wittman tell it, art thieves aren’t the sophisticated operators you see in the movies—but he still retired without solving the infamous 1990 heist at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the most valuable art crime in the nation’s history, despite several promising leads, which are recounted here.

—Sarah Cascone

Rainer Maria Rilke is, of course, best known for his inspirational book, Letters to a Young Poet. But this later collection also deserves attention. It contains Rilke’s collected letters to a young Balthus, who was just beginning to form himself as an artist. (Rilke was in a relationship with Balthus’s mother, and effectively served as a father figure for a time). Rilke’s encouragement to the young artist is inspiring and palpable, as is his care. (And Artnet News’ own Rachel Corbett, author of You Must Change Your Life, wrote the introduction.)

—Eileen Kinsella

Jonathan Harr, who is best known for A Civil Action, the true story that became a hit John Travolta film, weaves a compelling tale about the real-life rediscovery of one of Caravaggio’s greatest masterpieces. The canvas somehow made its way to a Jesuit residence in Dublin after being lost for centuries. Its resurfacing causes quite a commotion in the art-historical community, igniting rivalries and even outright feuds among scholars and connoisseurs. Of particular note for burgeoning art historians is that two young University of Rome graduate students, Francesca Cappelletti and Laura Testa, were instrumental in the work’s authentication.

—Sarah Cascone

Loot: The Battle Over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World by Sharon Waxman. Courtesy of Times Books.

This book may be over 10 years old, but the smuggling of looted antiquities is still a major problem facing the art world today. Delving into the history of Western collecting, Sharon Waxman makes it clear that most of the work in European and Western museums was acquired by methods that would be illegal today. (Hence the section on New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, titled “Tomb Robbers on Fifth Avenue.”) Loot also dives deep into the still-ongoing battle over the Elgin Marbles, taken from the Parthenon and today enshrined at the British Museum in London—much to Greece’s displeasure. It’s also interesting to be reminded of the comparatively recent missteps of the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, which not that long ago was the subject of a major controversy and a protracted legal dispute over its questionable acquisitions.

—Sarah Cascone