People

What Are the Challenges for a Young Artist Riding a Wave of Early Success?

Will Emma Sulkowicz be forever branded as the "Mattress Girl"?

Will Emma Sulkowicz be forever branded as the "Mattress Girl"?

Sarah Cascone

Is Emma Sulkowicz, the artist, here to stay?

In the aftermath of the release of Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, the recent Columbia grad’s controversial video art piece uploaded in June, she has become more famous than ever, but whether her current notoriety will lead to a long-term art career is an open question. Obviously, Camille Paglia doesn’t think so. But we have more hope for the young art graduate.

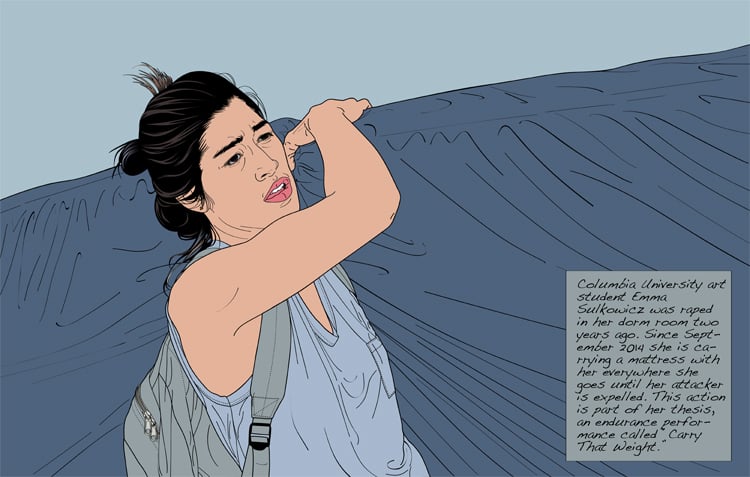

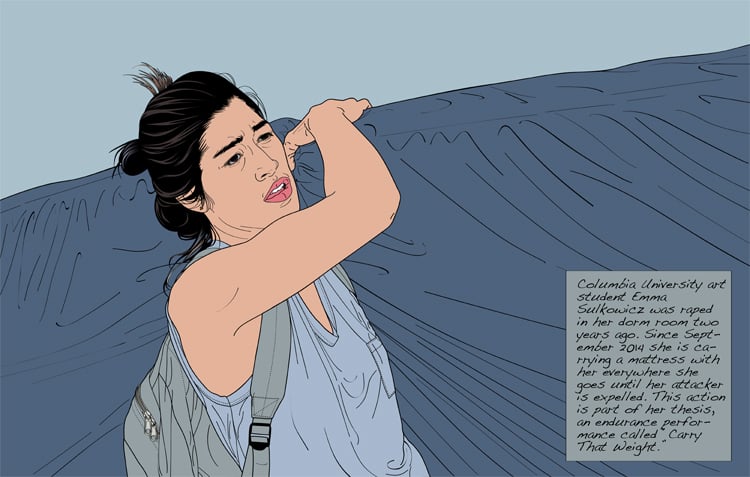

This May marked the completion of Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight), Sulkowicz’s senior thesis piece, in which she carried a standard issue dormitory mattress around campus in protest of Columbia’s handling of her rape claim. She vowed to continue the piece until her alleged rapist was expelled, or until she had completed her degree.

The work came to a dramatic end as she carried her bed across the stage as she graduated, and university president Lee Bollinger turned away from her, refusing to shake her hand.

Emma Sulkowicz carrying her mattress at her Columbia graduation in the conclusion of Carry That Weight.

Photo: the Columbia Spectator.

Already, she was looking ahead to the release Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, a video depicting Sulkowicz engaging in a violent and disturbing sexual encounter. “The internet is going to lose its shit, I think,” she correctly predicted in an interview with New York magazine shortly before its release.

When the media first caught wind of Carry That Weight, Sulkowicz was placed at the forefront of the sexual assault awareness movement on campuses across the country. As New York magazine put it in their September issue, which featured Sulkowicz on the cover, her poster-girl status “is an accident of a viral world.”

Rising to the unexpected occasion (“I had no idea it would get noticed by anyone when I first made it,” she told artnet News), Sulkowicz continued her outspoken activism, attending the State of the Union as the guest of New York senator Kirsten Gillibrand.

Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol seems a clear indication that her graduation day did not mark the end of her crusade.

Though Sulkowicz has made it quite clear that Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol is a separate work, the two pieces obviously mirror each other. However, it remains to be seen whether these two projects will serve as a springboard to a successful art career, or if she will become pigeonholed as the “Mattress Girl.”

Emma Sulkowicz.

Sulkowicz personally finds the nickname frustrating. “It’s like, okay great, so you think that I’ll never progress beyond that point. That I’ll be a ‘Mattress Girl’ rather than a living, breathing person who has the ability to change,” she told artnet News.

“It seems certain that the piece has set a very high standard for any future work she’ll do as an artist and will also earn her a niche in the history of intensely personal yet aggressively political performance art,” wrote Roberta Smith of Carry That Weight in the New York Times.

That larger history includes Ana Mendieta‘s Untitled (Rape Scene) (1973), which saw the artist recreate the crime scene of the rape and murder of fellow University of Iowa student Sara Ann Ottens. For the performance, Mendieta invited people to her apartment. Upon arrival, they found the door ajar, and Mendieta, bloody and still, naked from the waist down and bent over a table. “I didn’t move. I stayed in position about an hour. It really jolted them,” the artist later recalled.

Also troubling is Yoko Ono’s 1968 documentary film, titled Rape, in which she hired a male camera man to follow an unsuspecting woman named Eva Majlath through the streets of London.

Over the course of the 77-minute video, Majlath becomes increasingly distraught by the unwanted attention, attempting to evade her pursuer. The piece offers a powerful statement on the male gaze, standing as a precursor to Laura Mulvey’s essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” The camera’s unceasing presence is a clear violation of Majlath, both in mind and body.

Comparisons have also been drawn between Carry That Weight and Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Liebowitz’s Three Weeks in May (1977), which raised awareness of the problem of sexual assaults in Los Angeles through a series of public performances, charting every rape reported in the city during the project’s duration.

Nan Goldin, Nan One Month After Being Battered (1984).

Photo: Nan Goldin.

In publicizing her own personal victimization, Sulkowicz is perhaps best seen as successor to Nan Goldin, whose ongoing photo series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1981–) includes a chilling 1984 photograph of herself (Nan, One Month After Being Battered) with an intensely-swollen black eye, inflicted by her then-boyfriend.

“I wanted it to be about every man and every relationship and the potential of violence in every relationship,” Goldin said of the work.

Though Sulkowicz has likely assured herself a place in this art historical canon, the question remains: what next?

When asked about Sulkowicz’s prospects for a long-term career, dealer Jay Gorney was uncertain. “I think a great deal depends on the kind of work she continues to do, and the way her work is introduced both in a gallery and museum setting,” he told artnet News in a a phone conversation, noting that both Carry That Weight and Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol “have become notorious, but also do seem to have certain amount of power.”

Emma Sulkowicz, Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, screenshot.

For all the media attention she’s received, we still know little about Sulkowicz as an artist.

Prints Sulkowicz made for her senior thesis show were recently on view in “Surface of Revolution,” a group exhibition at the Southampton Arts Center drawn from the university’s LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies.

On paper, it’s an impressive first show, being displayed side by side with the likes of Kiki Smith, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Kara Walker, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Jasper Johns, and Lee Friedlander.

However, few people are writing about Sulkowicz’s prints. Instead, they are debating whether or not the mattress should wind up in a museum.

Sulkowicz is definitely open to the possibility. “If some sort of museum wants to buy it, then I’m open to that,” she told the Times, “but I’m not going to just throw it away.” She would like the mattress to be displayed with a recreation of the project’s “Rules for Engagement,” which she had painted on her studio walls, and the diary she kept for the duration of the piece.

In an e-mail to artnet News, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts director Harry Philbrick expressed interest in the mattress, which is reportedly stashed away in a Manhattan Mini Storage unit.

Emma Sulkowicz

Photo: Andrew Burton/Getty Images.

Were the Carry That Weight to wind up in an art institution, it would find itself in good company among bed-related art: Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998), a condom- and cigarette-strewn mess of wrinkled sheets that shocked and appalled audiences when it won the Turner Prize in 1999, is currently on loan to London’s Tate Britain after selling for $4.4 million at Christie’s.

Emin’s success in the years since could be a good model for Sulkowicz, who surely looks to avoid the fate of artists who have made splashy debuts but failed to sustain interest in their work. Gorney also points to Laurel Nakadate, who first became known for filming videos of herself seducing middle-aged men “and has since gone on to create other work that has been very well-received.”

For Sulkowicz, only time will tell.