Art & Tech

Art Duo A.A. Murakami Conjures an Immersive ‘Floating World’ in Times Square

Every night this month, a 'constellation of clouds floating' will descend on screens in Midtown.

Every night this month, a 'constellation of clouds floating' will descend on screens in Midtown.

Jiayin Chen

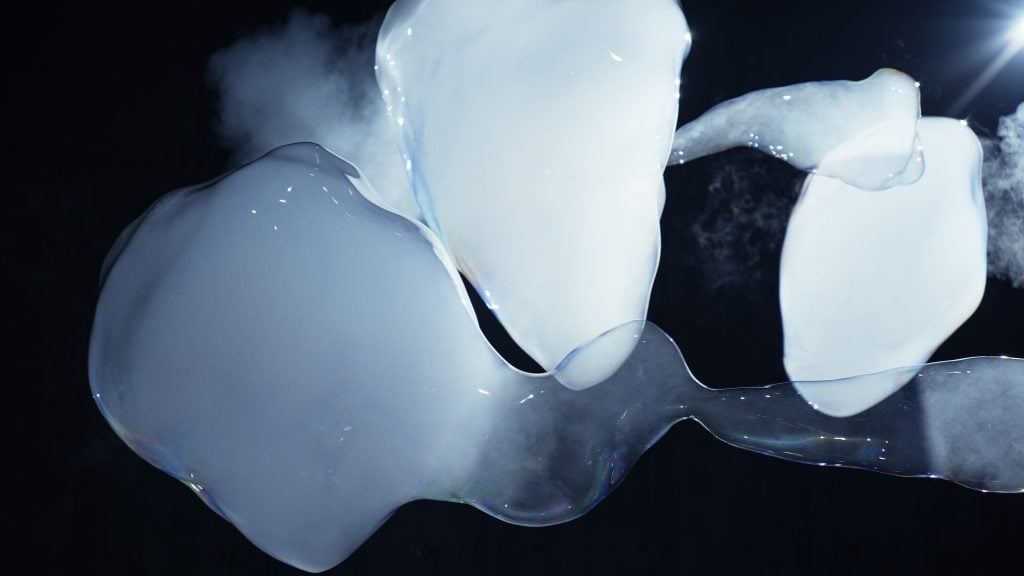

This October, massive mist-filled bubbles will emerge across a darkened landscape on the screens across Times Square at midnight. The digital work, Floating World, is part of an ongoing series created by the Tokyo and London-based artist duo A.A. Murakami (Azusa Murakami and Alexander Groves). The physical large-scale installation is currently on view at M+ Museum in Hong Kong.

Azusa Murakami and Alexander Groves. ©A.A.MURAKAMI, Photography by Emiliano Granado.

Known for their sensory-rich installations, A.A. Murakami explores the connection between humanity and nature, often working with ephemeral and unpredictable elements such as light, fog, scents, and plasma, as well as generative codes. Their work draws inspiration from ancient cultures, where they sought to emulate and honor the natural world, evoking a deeper awareness of the transience of human existence.

After months of virtual discussions and an in-person visit in Hong Kong, Artnet is thrilled to bring this digital adaptation to the iconic site of Times Square in New York City. The collaboration between Midnight Moment and Artnet co-presenting Floating World is an exciting moment, as A.A. Murakami stands on the cusp of a new era, with a busy lineup of museum shows ahead. This co-presentation also reflects Artnet’s core dedication to supporting digital art communities and enriching conversations at the intersection of art and technology.

Below is an excerpt from a conversation with Alexander Groves, one half of A.A. Murakami about the duo’s creative journey, the influence of nature and ancient traditions on their work, and the challenge of continually pursuing the “dream project.”

Congratulations on your largest physical installation to date, in the stunning M+ Museum. I was so enthralled by “Floating World”—it’s magical to experience in person. Where does the inspiration for the piece come from? Take us on the journey of how this project has evolved.

It first started with us working with bubbles filled with mist for our New Spring project that launched in 2017, and since then we have been working a lot with fog bubbles in different forms. The inspiration for the Floating World installation comes from the tradition of auspicious clouds in Asian art, which hold a dynamic sense of movement—coiling and uncoiling in a perpetual state of formation and dissolution, symbolic of the constant flux of existence, embodying the endless process of unfurling that reflects the transient nature of life and the bridge between the earthy world and the heavenly realm.

Famous Views of Omi, 1660s-90s. These byobu vividly portray the shores of Lake Biwa, located near Kyoto, and take a bird’s-eye view of verdant landscapes rendered with richly toned hues of thick mineral pigments. Photo by Heritage Arts/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

The idea of auspicious clouds—I can certainly see the connection when the fog is blown into the soap film. In ancient China, clouds are associated with Qi, the cosmic energy that flows through the universe and is constantly in flux. They also serve as symbols of luck. Tell me more.

When we went to Nanjing and saw the traditional embroidery used for making the Emperor’s robes, it was incredible. We saw similar work at the Palace Museum in Hong Kong, where clouds were depicted as motifs, symbolizing a bridge between the earthly realm and the heavens above. Clouds were also traditionally used as compositional devices, as in Japanese screen paintings where large, gilded clouds stretch across the screen, and between them, you see little bird’s-eye views of Edo or small, intricate scenes.

At the M+ Museum, we wanted to create a similar effect—using mirrors to extend the space and machines lined up to release clouds all at once. This creates a kind of constellation of small clouds floating in the room. In Chinese art, clouds are often depicted as dynamic, full of movement—unfurling and coiling. But when you look at real clouds, like from an airplane, they move across the sky, but not in the same swirling way. The scale is too large to notice without a time lapse. So, I think the clouds in our installation are closer to the stylized depictions of clouds in traditional art.

Installation view of A.A. Murakami’s Floating World (2024) installation at M+ Hong Kong. ©A.A.Murakami. Film and Photography by Adam Kovář and PETR&Co. Model by Ashley Lin.

Bubbles evoke a sense of joy and intrigue found in childhood, bringing with them a healing, almost meditative quality. In fact, bubbles are a household toy with a long history dating back centuries. I’m curious—what challenges did you face in using this age-old invention to create your new work? Was it calibrating the right humidity or finding the perfect bubble solution?

Well, bubbles love humidity because they need moisture to avoid drying out, so the best bubbles, according to the Guinness Book of Records, are made in warm, humid conditions. Thankfully, Hong Kong meets both criteria. Of course, even in dry conditions, we can adjust and calibrate the machines. What’s interesting about working with natural phenomena is that they interact with the environment, which makes them more engaging. When you experience something on a screen, it doesn’t physically interact with your surroundings.

Generally, there are a lot of logistics and factors involved in making the work of this complexity. It’s a combination of many disciplines—there’s electrical engineering, programming (since we set up an entirely new control system and software), chemistry in the bubble mix, mechanics in the moving parts, and fluid management. We’ve got tanks of fluid that have to be fed into the machines at just the right time. But you always have to remind yourself: the reason it hasn’t been done before is because it’s not easy.

When you were conceiving the work, did you envision it more as a large-scale installation or as a more intimate, performance-based piece?

Funny enough, we always envisioned it as a large-scale installation. The idea was to create a mini-environment or weather system that you could be fully immersed in, where you might lose your sense of space. But through making it and spending time with the work, I’ve come to think it would also be really suited to a smaller, more intimate setting. In a smaller space, the bubbles would feel somehow larger, and the encounter could be more eye-to-eye.

Your work often explores the ephemerality of nature and tends to be more tangible than digital. How do you define the role of technology in your work?

We call the type of work we create “Ephemeral Tech.” It’s proprietary technology, but what makes it unique is the interface—ephemeral materials like bubbles, fog, scent, and plasma. Creating fleeting moments that can be experienced with all your senses.

By using these fleeting, sensory-driven elements, we want to materialize the intangible nature of time itself.

Preview of the immersive “Silent Fall” Installation By A.A. Murakami at 6 Burlington Gardens on October 11, 2021 in London, England. Photo by Nicky J Sims/Getty Images.

Just as it is difficult to imagine that fire was once a new technology for humanity, it is also easy to associate the concept of technology with the artificial rather than with nature. However, if we fast forward 50 or 100 years, what we consider artificial today might be viewed as natural in the future. Where does A.A. Murakami’s desire to use technology to emulate nature come from?

Technology has always been a persistent force in human creation and culture, from cave art to standing stones, throughout the entirety of art history to the present day. People have consistently used the technology of their time to mark the passage of the sun or the migration of animals upon which their survival depended. Paying tribute to nature through emulation or representation is as old as culture itself, and our work continues this tradition by utilizing the latest technology available. It is driven by a desire to push the boundaries of what is possible and to use tools that extend beyond nature’s limits—much like Prometheus.

Yes, I just wanted to add that when I was there in person, it reminded me how much of our senses are muted or reduced, in today’s screen-based, modern life. We’ve become accustomed to a flat, visual overload. Being physically present with an artwork reconnects you to your senses in a powerful way.

Yes, exactly. The way we see technology is that our first passion is always the materials and the feelings they evoke. If you’re looking at a digital image, it’s not going to age; it’s not going to die—it doesn’t have that vulnerability. But when you’re experiencing nature, like cherry blossoms falling, there’s an awareness of its existence as a fleeting moment that we’ll never encounter again. I think that’s a powerful thing you don’t get when experiencing something on a screen.

So while I love experiencing things on screen, and of course, we couldn’t work without it, I also think it’s important to have massive, tangible experiences as well.

A.A. Murakami’s Floating World in Times Square. Photo: Michael Hull. Courtesy of the artist.

To experience the mortality of things

Absolutely, that’s why we call it ephemeral tech, because essentially, It’s about creating moments. We take the mysterious thing that is time, —we don’t really know what time is or where it exists —and we measure how things behave within time. For example, with watches, we use the vibration of a quartz crystal, or sand falling through an hourglass, or the pendulum’s regular, predictable motion to measure time. But you see, you are not really measuring time, you are measuring the matter — how the matter moves or behaves within time, we don’t actually know what time is.

We think it’s really interesting to create a moment that feels like you’re making time tangible. And I think that’s what bubbles do—it’s like you’re watching something come into existence and then slip out of existence. I see it a bit like the Light and Space Movement, where artists celebrated light and made it both the subject and the material they worked with.

Installation view of A.A. Murakami’s Floating World (2024) installation at M+ Hong Kong. ©A.A.Murakami. Film and Photography by Adam Kovář and PETR&Co. Model by Ashley Lin.

Times Square sees over 300,000 people pass through each day—how do you see “Floating World” connecting to or interacting with this iconic public space?

Our clouds, though strange and ethereal, evoke a sense of familiarity—reminiscent of the moon or the delicate, pulsating waves of jellyfish. In a space known for its intensity, we hope Floating World offers a meditative moment, an unexpected pause amidst the city.

With the digital adaptation in Times Square, the massive bubbles emerge slowly , allowing for more detailed observation as they appear in an enlarged format. This provides a fresh perspective, quite different from seeing them in person. Is the playback speed slower?

It’s a mix, actually. There were moments where we slowed it down and kind of cropped right into the bubbles. So you’re looking at the iridescent swirling on the surface. The reason we do that is because slowing things down gives them an epic scale, almost like looking at the swirling surface of Neptune or one of the other gas giants.

I think that just ties back to what you mentioned about time. As a digital artist, you have the ability to manipulate how these bubbles manifest within time, but you wouldn’t be able to do that with the physical work—it’s in the hands of nature when you create a physical experience.

Exactly.

You’re working across such a broad range of mediums and straddling many worlds at once. Do you think it still makes sense to separate design and art when it comes to your practice?

Yes, we do both design and art, but with different approaches.

We love both disciplines and want to achieve something in each, but with different kinds of work. With design, we love furniture and interiors—how they can enhance your everyday experience, what we call the art of living. With art, we love seeing an exhibition or reading a book and coming out the other side with new eyes.

What’s inspiring you at the moment? And is there a dream venue to showcase your work?

We are inspired by many things, but mostly by physics and the behavior of matter when it defies one’s expectations.

We’re always working on our dream projects—we don’t take on anything that isn’t one. If we have a new dream project, we start working on it immediately. What we can’t control are the opportunities to show these works. We dream of high-vaulted spaces with oceans of air in which to create our installations.

What comes to mind are spaces that weren’t necessarily built as art venues. For example, Tate’s Turbine Hall—it was a power station, but it offers such an amazing, huge void of space where you can work on a massive scale. There’s also the Grand Palais in Paris, where you have this expansive ocean of air above you, or the Prada Foundation, which is an absolute architectural masterpiece. And then we visited Hampi in India, a UNESCO site that was part of an ancient Hindu kingdom. The landscape and light there are just incredible.