Art World

Debunking Viral Story, Art Historian Says ‘Allah’ Does Not Appear on Ancient Viking Garment

Archaeologists and art historians find themselves embroiled in a white supremacist debate.

Archaeologists and art historians find themselves embroiled in a white supremacist debate.

Henri Neuendorf

Islamic art historians and archaeologists are calling into question a Swedish medieval textile expert’s claim that the word “Allah” has been found on a 10th century Viking funeral garment discovered in Sweden.

Annika Larsson, a textile archaeologist at the University of Uppsala, published an article on the Swedish university’s website announcing the discovery, and over the weekend a number of publications picked up the story, including the New York Times.

The story quickly went viral, largely because it seemed to counteract a far right-wing narrative that the Vikings represent a uniform Master Race. The march in Charlottesville most recently brought white nationalists’ appropriation of Nordic symbolism to national attention.

Dear Entire World: #Viking ‘Allah’ textile actually doesn't have Allah on it. Vikings had rich contacts w/Arab world. This textile? No. 1/60 pic.twitter.com/jpvbrrePQg

— Dr. Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

Stephennie Mulder, an associate professor of Medieval Islamic art and archaeology at the University of Texas, was among the first academics to question the findings publicly in a series of Tweets. Speaking to artnet News by phone, Mulder emphasized that she does not dispute that interaction between the Islamic world and the Vikings took place; rather it is this particular piece of evidence, and the way the story was reported by the media, that concerned her.

“The Vikings were traders and raiders who had extensive trade networks with the Arab world in central Asia up to [what is now] Iran,” Mulder said, “We’re used to seeing the Vikings as these brutal barbaric burners of monastery’s looking for gold, but actually they were savvy merchants and traders and moved things peacefully, like most people did in the Middle Ages.”

She explained that there are number of issues with the interpretation of the text on the Viking silk band that don’t add up.

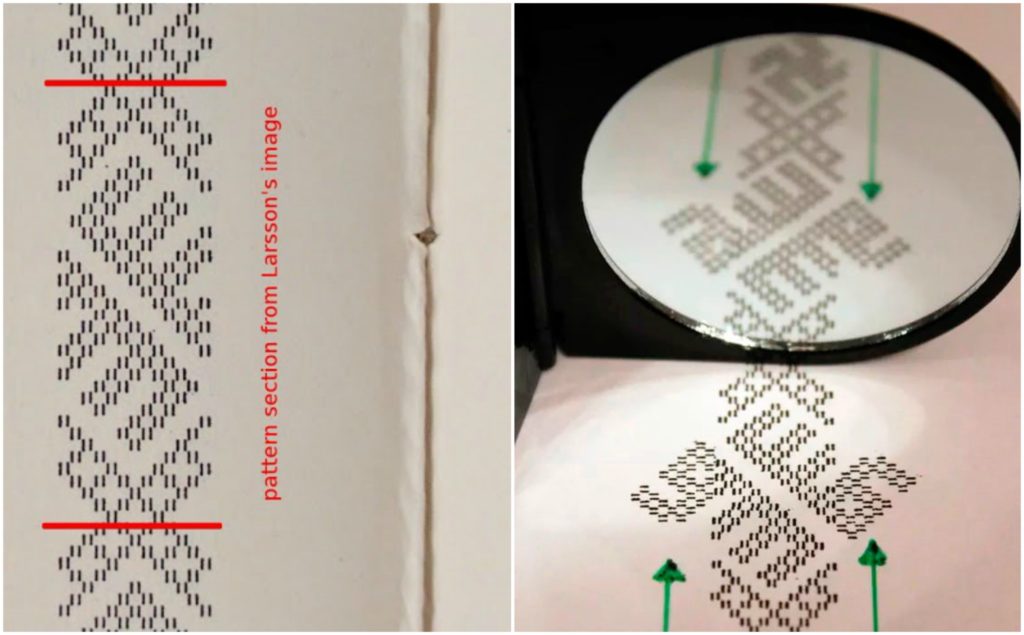

The final character in Larsson’s drawing has the Arabic letter ‘ha’ ـه with a hook over it which is not common until 15th century. Photo: Stephennie Mulder via Twitter.

The first and most glaring problem is that the text doesn’t seem to read “Allah.” Rather, it says something closer to “Ll-hah,” a discrepancy which Mulder said is easy to confuse because the letter “A” and the letter “L” look almost exactly alike in Arabic.

Additionally, there are no known examples prior to the 11th century of the style of Arabic writing that appears in the reconstruction drawing presented as evidence by Larsson, known as square kufic, Mulder said. The particular style in question, which features a unique hooked letter at the end of the word purported to say “Allah,” only appears after the 15th century. “Of course, something that comes 500 years later cannot influence something that came 500 years prior,” she said.

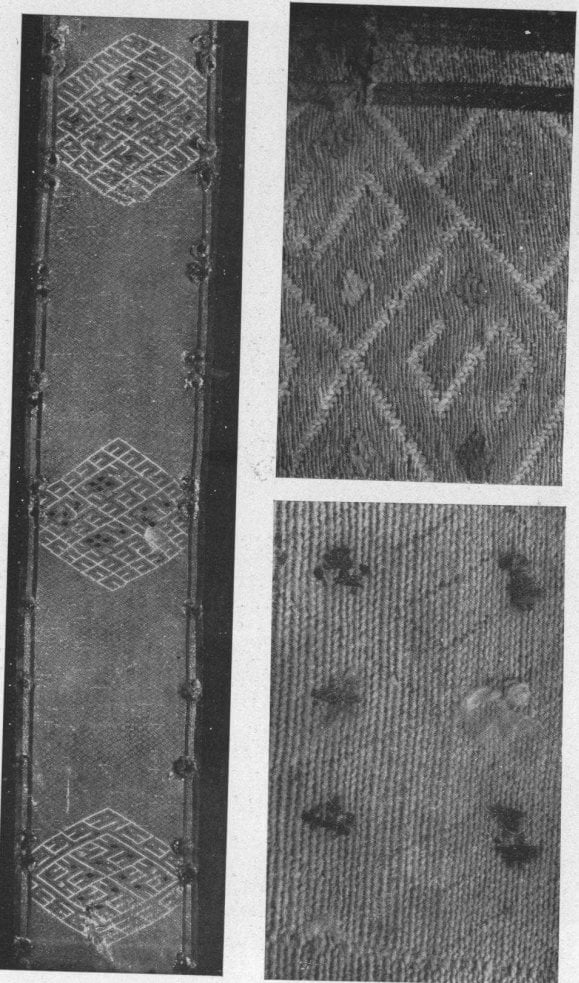

Examples of early Spanish textiles featuring square kufic script from the Monastery of Santa María La Real de Huelgas in Burgos, 13th century. Photo: Stephennie Mulder via Twitter.

Speaking to the New York Times, Larsson referenced a “Moorish design in silk ribbons from Spain” that looked similar to the script on the Viking funeral garb. After consulting a colleague who’s an expert in Medieval Spanish textiles, Mulder said neither she nor her colleague had ever seen this type of square kufic in woven pieces of textile prior to the 13th century, another 200 years after the 10th century textile purportedly turned up in Scandinavia.

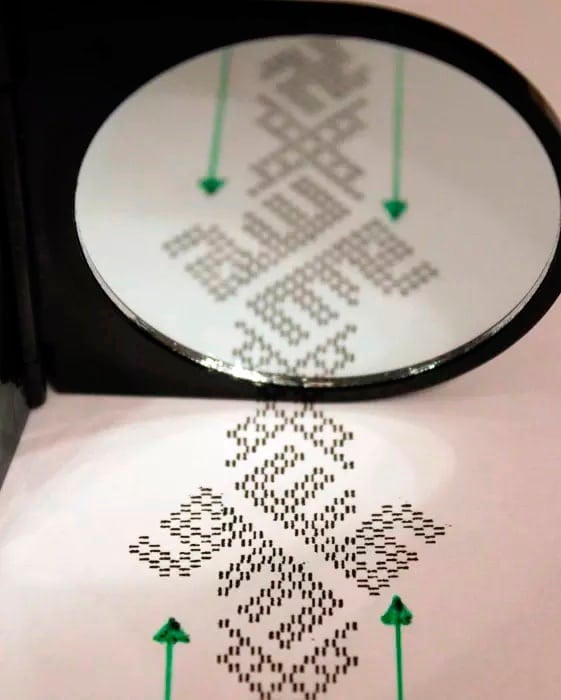

The green arrows point to the conjecture added by Larsson. Courtesy of Stephennie Mulder.

The final detail that puzzled Muldler is the composition of Larsson’s reconstruction drawing, in which she extends a conjecture of the patter past the silk band’s selvedge. “It’s like a ribbon with a finished edge on the top and bottom,” she said. “It would be impossible to argue that something had extended beyond the finished edge because the textile was designed to end at that point.”

Why does this matter? As Mulder explained on Twitter (across five tweets) “When [the] medieval and particularly [the] Viking age is used as [an] ideological weapon by white supremacists, and scholars are risking [their] careers to fight white supremacist appropriation, then it matters that we get this right. [The] media can report on [the] diversity of [the] global middle ages without trumped-up scholarship. We need news media to be our allies, consult experts, and get the facts right.”