The British charity Hospital Rooms has a clear mission to improve the standard of living for mental health patients through art. In the past six years, curator Niamh White and artist Tim A. Shaw have accessed the tightly controlled wards of the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS) buildings, collaborating with patients, clinicians, and artists at the top of their game, from Nick Knight and Julian Opie to Anish Kapoor and Tschabalala Self.

White and Shaw began the charity after witnessing the stark, clinical ward that housed a close friend who had been hospitalized. Their first project at the Phoenix Unit in South West London, which helps those diagnosed with schizophrenia, brought together artists such as Gavin Turk, Sophie Clements, and Knight. Since then, they have worked with over 20 wards and partnered with mega gallery Hauser & Wirth on a £1million ($1.2 million) fundraising drive, which is due to conclude in 2025.

Getting the attention of the health and art worlds, however, wasn’t easy. “When we started out, it took between 18 months and two years for anyone to let us in,” White said. “It is a high-risk environment where some people are very unwell. So many assumptions are made of people in these services, what they can and can’t do. I think we’ve had a small hand in changing [people’s] opinions by eventually walking into these closed spaces.”

Hospital Rooms has just launched its latest project: the creation of 15 artworks for three wings at the Torbay Hospital in Devon. Two existing wings involved collaborating with patients and staff; the third, which is brand-new, was conceived with local residents. Participating artists include Anna Chrystal Stephens, Tom Hammick, Huhtamaki Wab, and Simon Ripley.

“The Devon Recovery Learning Community put us in touch with people who have lived experience of mental health services or whose family and friends do,” said Anna Testar, Hospital Rooms’s senior project curator. “We did workshops alongside those in the hospitals, building relationships with nurses, ward managers, and occupational therapists.”

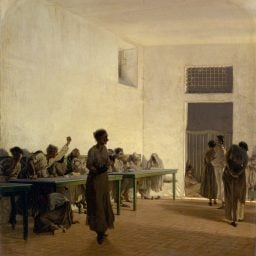

Tim A Shaw. Speakers Corner at Woodlands, a mental health unit that is part of the Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust. Image courtesy of Hospital Rooms; Photograph by Damian Griffiths.

“In the past, we have been very focused on ward communities,” said White. “Torbay is a unique place with its own culture and art scene. We wanted to understand more about the landscape and be a catalyst for future interventions.”

Hospital Rooms sits at a unique intersection between art and healthcare. The team has the freedom of working with patients and clinicians as outsiders. “It means we can come at things in a different way,” said Shaw. “It’s not feeding back into their therapy.” This gives patients some independence from clinical evaluations as being able to freely speak about challenging internal experiences isn’t easy for those who are being closely monitored.

“Someone on our team has lived experience of being on a mental health unit and has spoken to dozens of people on wards,” Shaw said. “Many fear if they express themselves genuinely, and it doesn’t come out as something nice and flowery, it could impact the length of their stay, their treatment, and the way they are seen by psychiatrists.”

“We make it very clear that we are coming in to solve a problem and make something together,” added White. “We don’t take notes on patients and nothing they make will be analyzed by anyone. It’s an equal partnership.”

Julie Allan has been an art therapist for 30 years, most recently at The Hellingly Centre—a psychiatric unit for those being detained under the mental health act and who also have had contact with the criminal justice system. She met White and Shaw in 2019, when Hospital Rooms brought artists including Richard Wentworth and Sophie Clements to create artwork with patients.

“The role can be to help people express and work through difficult emotions,” she said. “It’s very much about making sure it’s contained, safe, and that I have built a relationship with someone. There is a fear among other mental health professionals that someone is going to come to art therapy and bare their soul and it’s going to become very messy.” For Allan, art allows for a connection with difficult internal feelings that conventional talking therapies might not be able to. “I work with people who can’t talk about what they’re going through. They either cannot express their feelings or don’t understand them. Art can help with the process of unfreezing.”

Art and design are often the last priority—not always for a lack of interest but because of limited resources. This year, 13.8% of NHS funding has gone towards mental health care, including for individuals with learning disabilities and dementia. Allan also mentions the lack of research around art therapy, which means the benefits of such treatments have yet to be fully summarized in reports.

“We know it is powerful, but especially in NHS settings, people want figures and studies,” she said. “I would like to think there is more acceptance in recent years, but that’s not being [reflected in positions] created. Hospital Rooms have been incredible at promoting the healing power of art, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has spoken about it too.”

Sophie Clements, Games Room at Phoenix Unit, part of South West London and St George’s NHS Trust. Image courtesy of Hospital Rooms; Photograph by Toni Hollowood.

According to Shaw and White, Hospital Rooms is being inundated with new project requests. While art is a low priority for overstretched teams, the opportunity to have someone else solve the problem seems to be appreciated. “I think there is an inherited wisdom that if you’re unwell in any sense you should be in a white environment,” said Shaw. “It feels cleaner; it’s easier to keep track of people. If you need to value engineer something you lose the skylight, the art, the special things that make it more than a cell. We can hold a mirror up to that and say it is inhumane. That’s helpful because people are used to the way it is.”

Recently, Hospital Rooms has taken part in the design of two new units at Springfield University Hospital. Artists such as Susie Hamilton, Sutapa Biswas, and Yinka Ilori have all worked with patients on the project. The initiative also includes input from teams at the South West London & St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust, Norwich University of the Arts, the WHO, and Wandsworth Council as well as various local cultural partners. “The buildings at Springfield show a different way of doing things, with lots of light,” said Shaw. “Anna has also been working with artists on Torbay’s new ward to bring in stained-glass windows.”

Hospital Rooms takes the communities they work with seriously. Some patients have gone on to win art prizes and many have continued with their artistic practice. All of this has happened in line with a shift in the creative world at large, where community-driven art is no longer seen as less important. “If you were a community or participation artist, that was often seen as much lower than other artists,” said White. “We want to [elevate] the quality of everything that is associated with art and health. It’s rigorous, it’s valid; it’s just happening in different spaces.”