Galleries

In London, Art Has Fallen in Love with Design All over Again

Does having a function make art more valuable?

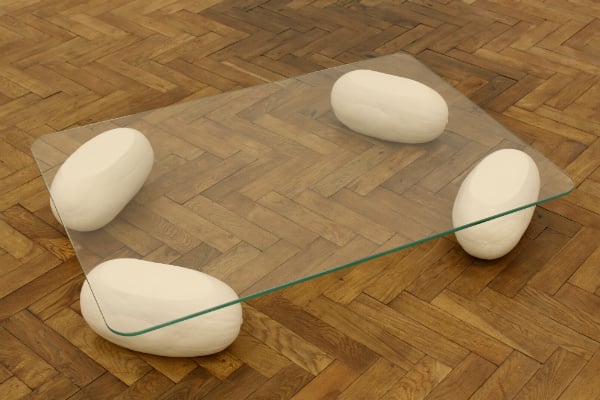

Photo: courtesy Kate McGarry

Does having a function make art more valuable?

Hettie Judah

Installation view of Alighiero e Boetti, Mona Hatoum, Rudolf Stingel, Mike Kelley, Mennonite Quilt, Amish Quilts and unknown artist, Deborah Pettway Young, Sterling Ruby, Franz West, Sergej Jensen, Danh Vo, Leola Pettway, Geraldine Westbrook, Katie Mae Pettway and William Morris

in “Losing the Compass” at White Cube Mason’s Yard,

Photo © White Cube, Stuart Burford

A curious nuance of utility is creeping its way across the London art scene: A whiff of functionality, a soupçon of the domestic, a smidgeon of the decorative. Thomas Demand and Arturo Herrera both designed their own wallpaper for recent exhibitions at Sprüth Magers and Thomas Dane respectively. More wallpaper, too, in “Losing The Compass” at White Cube Mason’s Yard, though this time designed by William Morris, and shown alongside textile works by Alighiero Boetti, Mona Hatoum, and Sterling Ruby, among others, and large handcrafted American quilts from the Amish and Gee’s Bend, Alabama.

Installation view “Losing the Compass” at White Cube Mason’s Yard.

Photo: © White Cube, Stuart Burford.

Not so long ago contemporary art and collectible design had a relationship akin to a pair of alley cats hissing at one another across the rim of a particularly pungent fishmonger’s dustbin. This post-Postmodernist (and post-Modernist) animosity arose around the same time as the now reviled term “design art” was coined, in 1999, by auctioneer Alexander Payne of Phillips de Pury. By 2008, even Payne had distanced himself from the term, but by then a rushy vogue for design art had driven a significant wedge between the two disciplines.

For a design world incredulous at the fortunes being spent on artworks that were technically the product of skilled fabricators rather than the named artists, the notion of adding value and collector appeal to their own work via more limited editioning was, self-evidently, appealing.

Sectors within the art world considered many designers to be cashing in on a hot art market by cynically creating gussied up “dictator chic” objets: Mirror-polished aluminium this, starchitect designed that, with a swooshy, glib aesthetic straight out of a CAD program and as much soul and nuance as a One Direction pub tribute band.

“Don’t Worry,” installation view at Kate McGarry.

Photo: Courtesy Kate McGarry.

Yet, less than ten years later, one of the most notable gallery openings of the season is Studio Leigh, a three story former varnish factory in Shoreditch that’s home to a soup-to-nuts artist furniture concept. For the debut show, gallerist Tayah Leigh Barrs gave 27 early-ish-career artists carte blanche to produce objects that were, if not full-blooded furniture exactly, certainly engaging with the vernacular of design.

Aaron Angell, Planchette (2015).

Photo: Courtesy Studio Leigh.

For some works, the artists were matched with craftspeople, including boat builder Stanley Smallcraft, responsible for Aaron Angell’s seaworthy Planchette, a jollyboat-cum-cat-memorial. Some, such as Nicolas Deshayes’s transformation of one of his colonic forms into a functioning radiator in Filth Takes Off Its Shirt, provide a grimly satisfying extension of existing concerns. Others, notably Richard Gasper’s self explanatory ceramic work Flower Toilet, blow a cheeky raspberry to the commissioning concept, to the godfather of the readymade, and to the attendant notion that a designed object attains mystic value when raised to the status of art.

After a few years of artist-as-archivist, artist-as-collector, and the interest surrounding the relative status of found and made objects and human and non-human life, these objects with their hint of the day-to-day seem like an extension of an ongoing discourse rather than an incursion.

Matt Ager, A Little More Room (2015).

Photo: Courtesy Studio Leigh.

Having shown Martino Gamper’s work in Feierabend with Karl Fritsch and Francis Upritchard in 2009, London gallerist Kate MacGarry can to some extent claim responsibility for the enthusiastic art world embrace of the designer, who was the subject of an exhibition at the Serpentine last year and is currently front and forward in the Leeds iteration of the British Art Show 8. MacGarry showed the work of designer Max Lamb alongside Luke Gottelier this time last year, and has just opened the group exhibition “Don’t Worry,” in which furniture by designer Muller van Severen can be seen alongside ceramic sculptures by Dan McCarthy, a work in vinyl wallpaper by Olaf Breuning, a woven wall hanging by Peter McDonald, and riffs on domestic iconography from FOS.

Muller Van Severen, Rocking Chair

Photo: Courtesy Kate McGarry.

That list of media is significant—this revisitation of design takes place alongside a renewed interest in craft-associated techniques, including ceramics and weaving. A shift acknowledged, too, in the art and craft mix of the textile-centric “Losing The Compass” at White Cube. On the flip side, a number of designers have emerged over the last decade whose conceptual and process-led practice sits quite comfortably alongside their art world peers. Max Lamb, Martino Gamper, Studio Swine—whose Hair Highway (2014) project deployed human hair as a renewable resource—and Minneapolis-based Jonathan Muecke’s roots-up re-conception of furniture typologies, are among them.

The work of these and other designers acts quite satisfyingly as a conceptual counterbalance to the current art world tendency toward craft and the domestic vernacular. Much to love, then, on both sides.