In recent years, the public has increasingly scrutinized museum collections that disproportionately represent dead white male artists—a process that was accelerated radically in 2020 after a groundswell of support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

“With the killing of George Floyd, there was a new urgency around these issues,” Sasha Suda, director of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, tells Artnet News.

While some rushed to make gestural purchases of works by Black artists, others seized the moment to look inwards at the systemic issues that resulted in imbalances in their collections.

“It really sent shockwaves through the whole sector, and certainly within Canada, it dovetailed with a lot of conversations we were having around [issues regarding] First Nations,” Suda says.

But this new energy has coincided with a massive financial crisis that has also forced many institutions to deprioritize growing their collections in the immediate term in favor of wider organizational needs. Now museums have to consider how to make their diversification commitments sustainable, and how to shelter them from future crises.

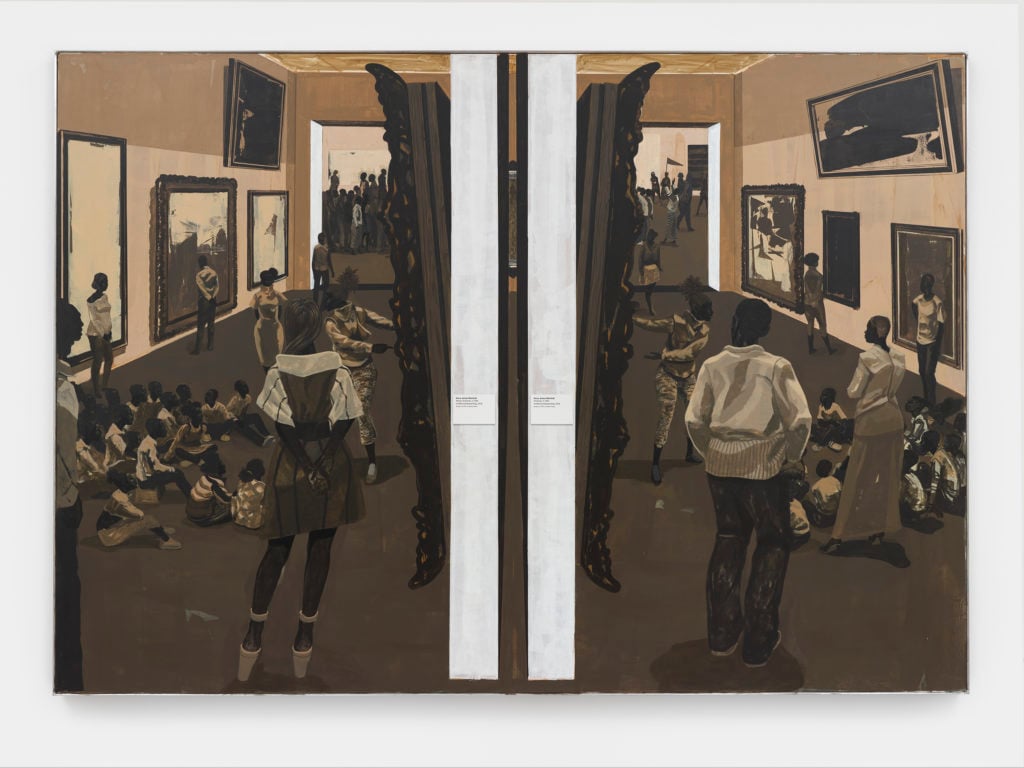

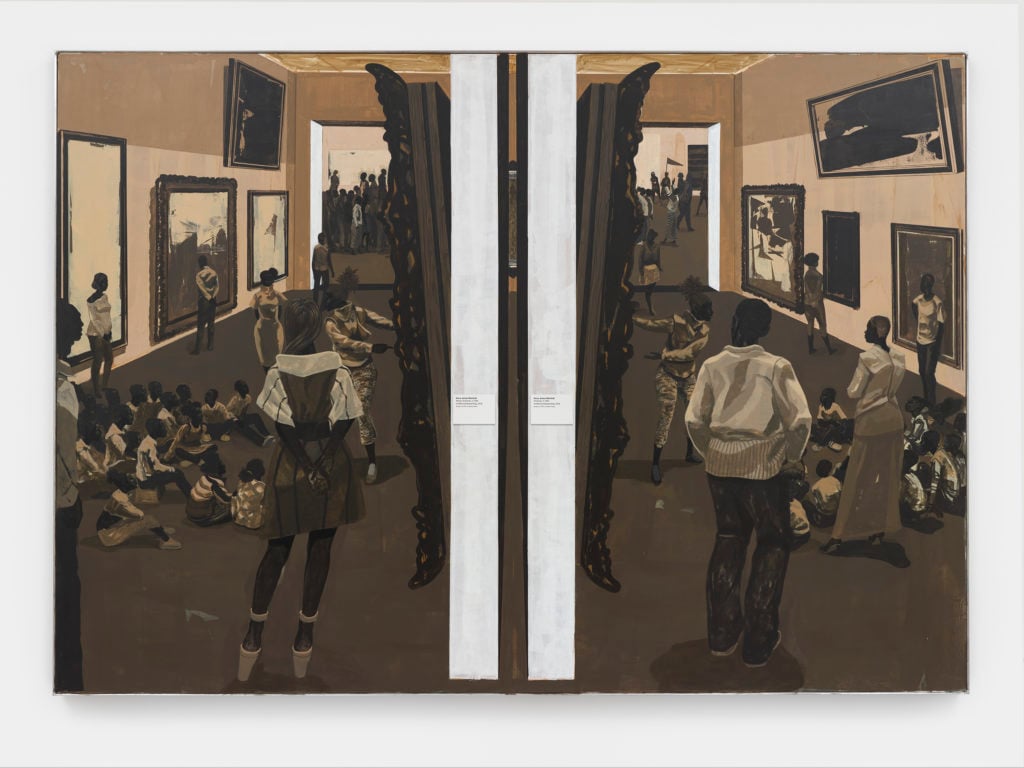

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Underpainting) (2018). © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

Bold Statements and Bold Actions

Some institutions, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are making bold statements: the museum announced last year that it intended to build a $10 million acquisitions endowment for works by BIPOC artists.

But other museums are taking more radical steps to reimagine their holdings.

In 2018, the Baltimore Museum of Art sold off a group of works by white male artists to create a fund to acquire more examples by women and artists of color. Last year, despite successive lockdowns decimating income, it was able to use these funds to spend $2.57 million on 65 works by 49 female-identifying artists, including 40 who had not previously been represented in the museum.

Lois Jones, Untitled (Two Women) (circa 1945). The Baltimore Museum of Art. Image courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

The museum’s director, Christopher Bedford, says the restricted endowed for such diversity acquisitions, as well as the remaining pot from the 2018 deaccessions, will ensure a continued emphasis on collection development in 2021.

Similarly, SFMOMA, which raised $50 million to fund more diverse acquisitions by deaccessioning a Rothko in 2019, has been able to acquire 91 works by Black artists, including 55 by purchase, in the past fiscal year.

But the strategy has proven to be controversial. Selling off artworks is an unpopular move, and a subsequent effort by the Baltimore museum to deaccession tens of millions of dollars worth of artworks last fall was halted in the 11th hour after blowback from critics and a museum trade group.

Frank Bowling, Elder Sun Benjamin (2018). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. © Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/DACS London; Photo by Katherine Du Tiel.

The Stress of the Pandemic

Elsewhere, the pandemic has forced institutions that have acknowledged diversity gaps in their collections to scale back their ambitions.

In the UK, where endowments are a rare luxury, acquisitions capacity was already limited before the crisis. Very few museums have dedicated funds for acquisitions at all, and those that do tend to be diminutive: in 2019, more than half the museums that are supported by the Contemporary Art Society, a charity, reported acquisitions budgets of less than £5,000 ($7,000).

Additions to collections for the most part depend on a combination of donations, gifts, and bequests, over which museums have little control.

As a result, UK museums do most of their collecting passively, and have a harder time filling specific gaps. There is also a strong feeling against deaccessioning, which is widely viewed in the country as a fast track to impoverishing collections both now and in the future, as future donors could be deterred from giving art if they perceive their gifts to be tradable assets.

The pandemic has put even more pressure on already lean budgets, as resources that might have been set aside for acquisitions in another year have been co-opted into supporting organizations’ wider operations.

Contemporary Art Society. Photo via: Art History Abroad

In its official vision statement for 2020–25, Tate listed increasing its holdings of works by women, LGBTQ+, minority, and artists of color as a priority. The institution’s two heads of the collection, Polly Staple and Gregor Muir, told Artnet News in a statement that the pandemic has “inevitably required us to recalibrate the pace and scale with which we grow the collection at present.”

Yet Caroline Douglas, the director of the Contemporary Art Society, tells Artnet News that the desire among UK museums to diversify their holdings “has absolutely accelerated this year.”

More than 68 percent of the acquisitions the charity made for museums this fiscal year, which totalled around £540,000 ($750,000), were by Black artists and artists of color, up from around 21 percent the previous year and 39 percent the year prior.

Elsewhere in Europe, institutions are trying to write their efforts into longer-term strategic goals. The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, for example, committed to spending at least half of its acquisitions budget—whatever the figure—from 2021 through 2024 on works by artists of color and those from outside Western Europe and North America.

The Stedelijk Museum. Image courtesy of the museum.

The Big Picture View

The Stedelijk’s plan suggests another, deeper question: how exactly should museums work?

“Multiple groups have been putting pressure on museums to rethink the way they do business,” says Naomi Beckwith, the soon-to-be deputy director and chief curator of the Guggenheim. “That really came to a head after the death of George Floyd, so now institutions that have felt they could ignore these issues realize they no longer have that luxury.”

“This can’t be the project of one curator or one director,” Beckwith adds. “This has to be an ongoing project written into the new formation of institutions. I think this is one of the primary shifts from diversity work—which is just ‘get more in’—to equity work, which is about restructuring how we think and how we function to make diversity a by-product of that.”

In other words, increased acquisitions alone will not bring about equity.

“For these kinds of changes to course through the museum system, you’re talking about years and years of painstaking work,” says Andras Szanto, and author of The Future of the Museum.

“The scholarship involved, the staffing up of expertise, the rewriting of the narrative, the re-engagement with the audience—these are things that are not happening overnight.”