Art World

Art Schools of the Future Need to Teach Students to Understand Technology. How Will That Change the Future of Art?

Art schools have been slow to adapt to the digital revolution. Now, they're finally catching up.

Art schools have been slow to adapt to the digital revolution. Now, they're finally catching up.

Sabrina Faramarzi

Are you a sculptor? A painter? An illustrator? For decades, art students starting out have asked themselves these questions. But these categories could look very different in the near future, as art schools belatedly attempt to incorporate new technology into their curricula.

Earlier this year, one of the world’s most prestigious art schools, The Royal College of Art in London, announced plans to expand its curriculum to include science and technology. It was a watershed moment that suggested some art educators are finally understanding that these subjects need to be part of the academy in order to for it to survive the digital age.

But how can art schools adapt to this new paradigm, and how will the changes inform the kind of art that will be made in the future?

There has been much discourse about how education needs to expand from STEM to STEAM, incorporating art and creative thinking into more right-brained areas of innovation. But so far, the science sector has been more open to welcoming art than the reverse.

According to the 2019 State of Art Education Survey, 52.2 percent of art teachers want to learn more about teaching digital art effectively, but only 21.9 percent of art teachers feel comfortable actually teaching a digital arts curriculum. Schools like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and New York University, meanwhile, have already incorporated arts education into their historically science- and technology-led curricula.

The University of Arkansas art school. Courtesy of the University of Arkansas.

“Many art schools have been cautious to adopt anything that feels too vocational or applied,” says Luke Dubois, an associate professor of integrated digital media at NYU. “Art schools need to focus on career training that stays within the values of the arts.”

Professor Mick Grierson, a research leader at the newly opened Creative Computing Institute at the University of the Arts London, attributes the gap to ideological friction between arts and technology. Some traditional creatives are not only unsure how to integrate technology into their lessons, but also hesitant to see coding and other tech stills as artistic practices in and of themselves.

“There are plenty of people who, for decades, have been in the art and design community but haven’t really been able to find a home for their technology-led creations and practice,” he says. “So of course, they naturally migrated to a STEM environment because it’s easier for them to talk about the materials they use and the approaches they take.”

As a result of this culture clash, digital artist and educator Vicki Fong believes arts schools have missed a huge opportunity—and art is suffering as a result. “People are using digital skills to speed up the process, so more art is being made at a much quicker rate, which doesn’t necessarily increase the quality,” she says. “Digital art so far has been about production, about churning things out. I think that mentality is shifting now.”

One thing is clear: many artists won’t just naturally begin incorporating technology into their work without schools teaching them how. In a 2016 report, “Discovering the Post-Digital Art School,” arts educators Charlotte Webb and Fred Deakin note that “the notion of a current generation of young digital natives who inherently understand the internet with all its culture, grammar, and protocols, and who can effortlessly create innovative digital content and projects in ways that their teachers could never understand, is now acknowledged as simply a paranoid myth,” they write.

There are schools that do digital arts education well, like UCLA’s Design Media Arts curriculum, which uses technology-powered art processes without putting too much of an effort on commercialization. As curator and cultural strategist Julia Kaganskiy notes, schools that excel in this sector integrate both technological thinking and practice. The field cannot simply be viewed as an add-on—it’s critical for any artist who wants to be able to respond to the state of the world.

A counter investigation into the murder of Halit Yozgat. Courtesy Forensic Architecture.

“As software, algorithms, non-conscious cognitive agents and cybernetic thinking increasingly shape the world around us, artists need to have a strong grasp of the practical and philosophical implications of this transformation,” Kaganskiy says. “I’m not saying that every artist needs to learn to code, but they should probably read some media theory and software studies texts, maybe even some posthumanist philosophy.”

Brilliant technological arts education needn’t only happen in formal learning environments. The artist-run School for Poetic Computation, founded in 2013, has students and faculty work together on projects to explore the intersections of code, design, hardware, and theory. The idea is that true digital arts education needs to be collaborative—something that commercial technology spaces idolize above all else—which is perhaps why some of the most successful digital art is coming from groups like teamLab or Forensic Architecture, rather than individual practitioners.

In order for digital art to be treated as seriously as analog art, however, experts say that universities will need to adopt an even broader shift in thinking.

“The biggest problem that digital art forms have faced is that scarcity equals value, and being readily available means these works essentially are worthless,” says Mick Grierson. While some services now offer digital art as limited editions and authenticate it using blockchain, the sector will inevitably require the art world to broaden its understanding of value and access, at least to some degree.

Vicki Fong thinks that the future of digital art will be exhibited in online, virtual spaces. “There is already emerging this market where individuals that are interested in buying digital assets,” she says. “If we think about Millennials and Gen Z who may not own physical spaces but who have more of a digital online existence—they will want these assets to dress their virtual spaces.”

An immersive artwork replicating the experience of stepping into the gravitational waves of a black hole by audio-visual pioneers Marshmallow Laser Feast, installed in the 1830 warehouse at Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum, as part of Manchester Science Festival. (Photo by Peter Byrne/PA Images via Getty Images)

The technification of the art school curriculum still has a long way to go, and art educators need to do more than just prep students with Adobe suite skills. Considering that art school will cost students an average of $64,068 in the US and between £35,000 in the UK, potential art students need to be reassured that the education can be tailored to the contemporary art landscape.

The appetite is there: Earlier this year, the VR art collective Marshmallow Laser Feast was the subject of an exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, which was not only a sold-out hit, but was also extended for an additional five months, showing that audiences have a strong appetite for digital art that is both thoughtful and critical.

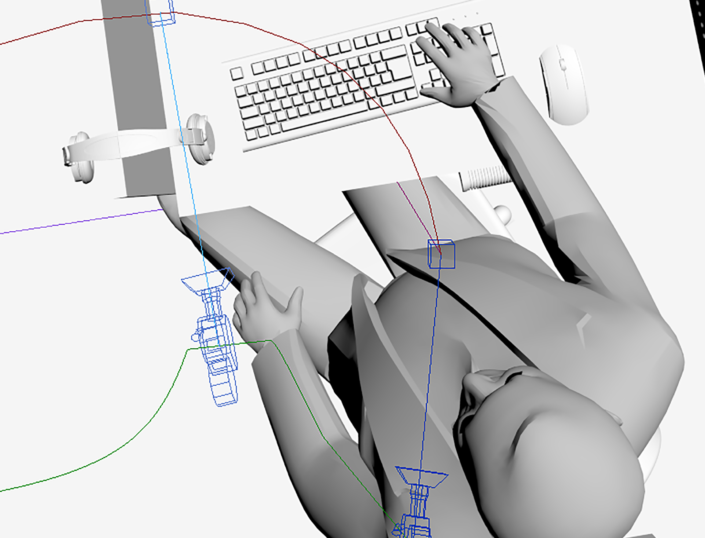

Despite the fact that the first computer art exhibition took place in 1965, art schools are still slow to put computerized art into the hands of artists instead of commercial tech mavericks. “It’s like the art school has handed the baton of creativity over to the computer scientists and programmers, who often make terrible art,” says digital artist Alan Warburton.

And indeed, whether a work of art is made with acrylic paint or code, some say the qualities that make it meaningful are the same—and that is something only art schools can teach. “Too often artists (and curators, and audiences) get caught up in the novelty of the tool itself and sacrifice substance in the process,” Kaganskiy says. “It’s fine to explore a tool’s formal and aesthetic possibilities, but art needs something to say. Technology will continue to change, but that desire for connection or transcendence is constant.”