Art & Tech

‘We Cannot Fight A.I.’: How Art Schools Are Navigating the Challenge of Artificial Intelligence

Will art schools know if applicants created their entire portfolio using A.I.? Will they care?

Will art schools know if applicants created their entire portfolio using A.I.? Will they care?

Brian Boucher

“It feels like the birth of photography all over again.” This was the verdict of Mike Essl, dean of the art school at New York’s Cooper Union, in a recent video interview about the challenges artificial intelligence is bringing to art schools, including whether this new tool—much like the camera before it—qualifies as a medium for making art.

While the rapid rise of A.I. creates as many possibilities as harms in the art world, it introduces its own set of concerns for schools of art and design. Will admissions officers know whether the artworks in an applicant’s portfolio were created with a few keystrokes, for instance? How should professors appraise works created entirely with A.I.? Will a degree lose value to prospective employers as A.I. becomes more powerful?

Tim Flattery, provost and vice president of academic affairs at Detroit’s College for Creative Studies (CCS), which educates automotive, fashion, and game designers along with studio artists, acknowledged, in a video interview, a “general concern” among his peers about the latter question.

Tim Flattery. Photo: College for Creative Studies.

Humans will always be needed in the design process, Flattery said. Drawing a parallel with the then-ongoing Hollywood writers’ strike, he noted that the writers wanted an acknowledgement of the fact that they have emotional intelligence. “They don’t want producers to think they can just write a prompt and call themselves a writer.”

But Nate Harrison, dean of academic affairs at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (SMFA) at Boston’s Tufts University, thinks “concern” about A.I. is no longer relevant. It’s here.

“We cannot fight A.I.,” he said. “Students are already using it, many very organically and intuitively and naturally.” In his view, the question is, “How can we equip students with smart approaches to using A.I.?”

The rise of A.I. is frequently called “unprecedented”—rarely is a tool used for making art also said to threaten the existence of humankind. But in fact, as Thomas Duncan, SMFA’s director of admissions, noted in a phone interview: “This is a conversation that has happened in art forever. Sculptors were once accused of casting the human body, but the whole framework of a sculpture isn’t ‘did you do it with your hands?’ We’ve opened the field to a lot of techniques.”

Moreover, the recent invention of products like the Adobe Creative Suite, including powerhouse programs like Photoshop, gave rise to similar fights; but, CCS’s Flattery said, there’s a big difference between the output of those tools in the hands of artists and those without artistic skill.

Mike Essl, dean of the art school at the Cooper Union. Photo Leo Sorel, courtesy Cooper Union.

Essl, for instance, remembers that students were forbidden to use computers when he was a freshman at Cooper, but having just learned to use programs like Adobe Pagemaker, he couldn’t resist. “So I did a project on the computer and made it look like it was hand-done—I took a little bit of black ink and flicked it on the page—and turned it in.”

Yet when it came time for a critique, he recalled, the discussion of his work was just as productive, even if the work took less time to make.

“Limiting the tools,” he concluded, “is not a good practice for artists.”

The academic building at the Cooper Union in New York, built in 2009. Photo by Ajay Suresh, Flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic.

But if applicants can potentially generate an entire portfolio using A.I. programs such as Midjourney or DALL-E, how do schools ensure that students who arrive on campus can create their own compelling work?

“That is the conversation right now,” said Deborah Obalil, president and executive director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD). “And no one has the answer.”

About a decade ago, she explained, an influx of firms occasionally skirted ethical lines in assisting international applicants to U.S. art schools, leaving administrators unsure whether the person who conducted the English-language telephone interview or created the application portfolio was the one who ultimately showed up on campus. But in the end, she said, the vast majority of applicants were not trying to scam the system.

The School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University. Photo: Anna Miller/Tufts University.

Will the same turn out to be the case today?

Views on this are mixed. As New York University professor Winnie Song bluntly put it in an interview with Vice: “These new students are coming in from high school, from another life that we don’t know. I think it could be possible for them to have created a portfolio out of thin air overnight using these generators, depending on how good they become.”

And while CCS didn’t see much of this with the last cycle of applicants, Flattery said, “We do expect it in the next.” Compounding the problem: what was easily recognizable as A.I. even a year ago no longer is. “A.I. has evolved,” he pointed out. “It’s going to be harder for admissions teams to discern whether someone is really adept at writing prompts.”

But SMFA’s Nate Harrison is less worried. “We’re not in the business of training future designers and illustrators but rather artists,” he said. “We can help you hone a creative practice that can’t be put into a text prompt.”

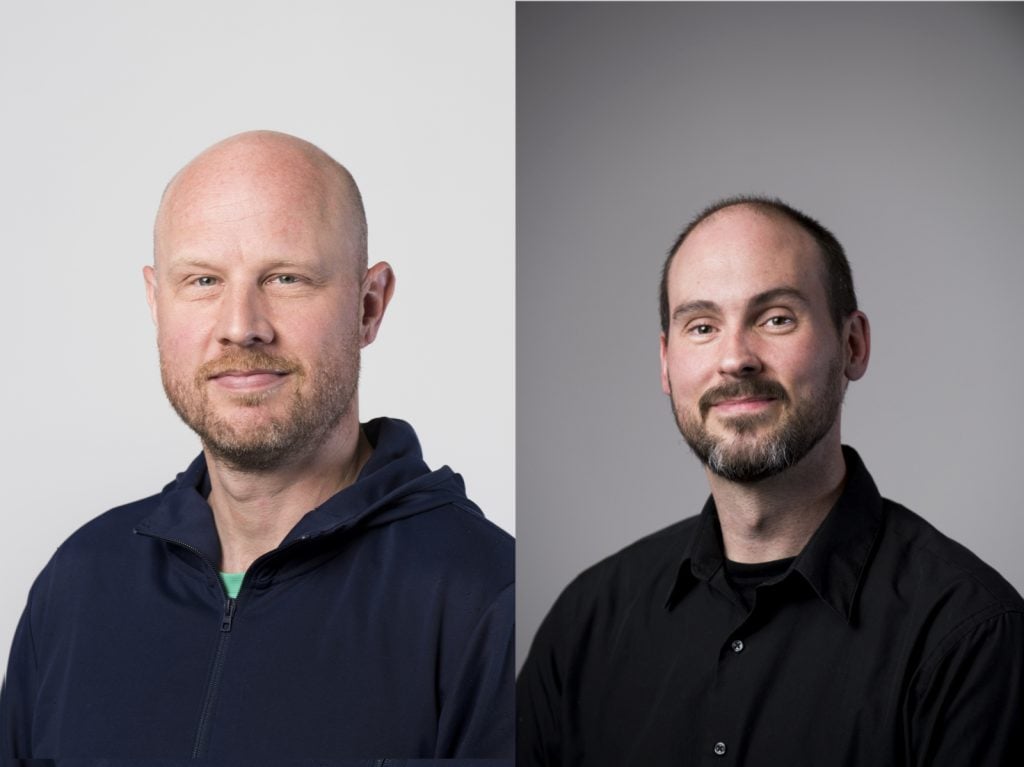

Left: Nate Harrison, Dean of the Faculty and Professor of the Practice at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University. Right: Thomas Duncan, Director of Admissions. Photos: Alonso Nichols/Tufts University.

His colleague Thomas Duncan agreed. “I see a lot of conversations about A.I.-generated images in portfolios framed as A.I. being a threat to the way admissions offices will be able to assess a prospective student’s technical skill,” he said. “But that’s really not the primary thing we’re assessing.” At SMFA, he said, he’s curious about “how a student is going to be as a community member, who they will be in the classroom, what kind of artist they will be.”

But then, art schools vary widely in what they teach. Unlike SMFA, CCS sends graduates into the automotive industry, where products have more stringent requirements than, say, a painting that hangs in a gallery.

On campus at Detroit’s College for Creative Studies. Photo: College for Creative Studies.

Consequently, some, like Elliott Earls, head of the graduate graphic design department at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, believe that art schools may resort to proctored or standardized measures, like SATs, to make an end run around applicants’ potential deceits. He lays out his predictions in his YouTube lecture “Artificial Intelligence and the Looming Admissions Crisis.”

At CCS, officials are taking another approach, convening town halls with industry professionals. A newly written institutional statement acknowledges that artists and designers on the job market will be expected to be able to collaborate with A.I. systems. But it also tells students that A.I. systems should be used only in research, not final outputs; that they must reveal their uses of A.I.; and that prompts can’t include the names of existing artists or brands. Applicants are limited to one work per application portfolio created using A.I.

Photo: College for Creative Studies.

Still, Cooper Union’s Essl remains sanguine. “We’re not that worried about it,” he said. “If a student figured out a way to use A.I. to make something interesting and included it in their application, I as a reviewer would be interested in what they’re thinking about and what they made.”

SMFA’s Duncan takes a similar attitude. The school asks applicants to identify their A.I.-created works, but also to tout them.

“We pose the question, ‘how did you use A.I. in your portfolio?’ not to ask students to turn themselves in for cheating, but to brag about the techniques they’ve figured out,” he says. “We’re excited about A.I. too—we want to be co-conspirators with them!”