Italian director Giuseppe Capotondi doesn’t want art audiences to take his new thriller, The Burnt Orange Heresy, too seriously.

The film, which opens in New York and Los Angeles today, is based on the 1971 novel of the same name by Charles Willeford. It stars Claes Bang as a womanizing art critic named James Figueras who appears to have pulled some dubious market related stunts in the past. Elizabeth Debicki plays Berenice Hollis, his lover turned travel companion, while Rolling Stones frontman Mick Jagger takes a turn as a scheming, white-suited art dealer named Joseph Cassidy who sports a perpetual evil grin, while a shaggy Donald Sutherland plays a mysterious artist genius named Jerome Debney.

Claes Bang as James Figueras and Elizabeth Debicki as Berenice Hollis. Photo by Jose Haro. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics.

When Cassidy summons Figueras to his lavish villa in Lake Como, Italy, it’s not without a questionable agenda, starting with getting Debney to agree to an interview and to uncover the mystery of the devastating studio fires that destroyed the artist’s work. The ensuing plot twists, insider jokes, and wry conversation make for an entertaining mashup that lands the film somewhere between Velvet Buzzsaw and American Psycho.

Capotondi says that the first thing he did when he got the script was change the setting from Palm Beach, Florida, to Lake Como to increase the film noir effect. “I thought it would make it more moody” to serve as a more fitting backdrop for the plot’s darker undertones, Capotondi told Artnet News.

Then, finding visually appealing actors with a commanding presence was key. “First off, given such beautiful dialogues, I needed the cast to be very handsome in an old-fashioned, film noir style. All of the characters are tall, beautiful, and commanding. They’re all very well dressed and well spoken,” he said. “I needed a sort of devilish character for the dealer and I thought Mick Jagger would play it very well and in fact he did. It was really nice to work with him. He was very gentle and humble, in fact the contrary of what you see on set.”

Elizabeth Debicki as Berenice Hollis and Donald Sutherland as Jerome Debney.

Photo by Jose Haro. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics.

Several real-life players in the art world also make cameos, including writer and curator Phong Bui and Pace Gallery’s David Goerk, as does art by Carol Rama and Alighiero Boetti, alongside Arte Povera stand-ins such as a white wrinkled canvas that looks distinctly like the work of Piero Manzoni. (Arte Povera occupies “a special place in my heart,” Capotondi says.)

There’s gems of dialogue throughout, such as when Cassidy asks Figueras which living artist he would most like to interview, and Figueras responds, “Anselm Kiefer.” Cassidy fires back: “Kiefer would speak to anyone with an open notebook.”

When Figueras and Hollis first arrive at the villa and are waiting on Cassidy to appear in the dining room for lunch, they’re eyeing two canvases with raw, graffiti-style block letters that spell out versions of the word “STAMMER.” Figueras weighs in on the works, which Capotondi says were inspired by artist Christopher Wool, telling his friend: “He overpaid for these, in a few years they will be worth a lot less.”

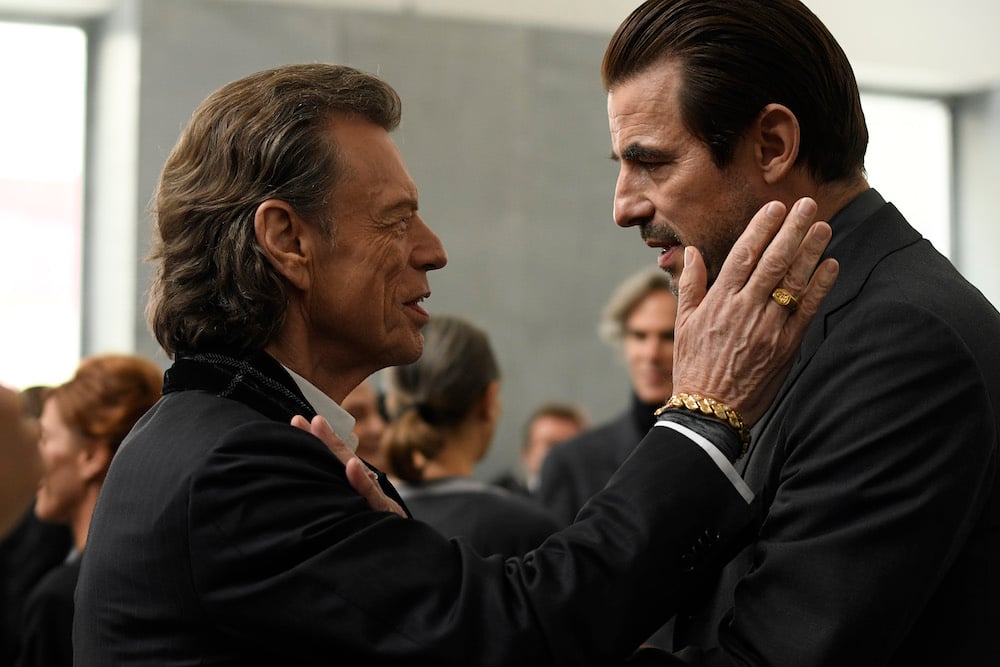

Center: Mick Jagger as Joseph Cassidy. Photo by Jose Haro. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Unbeknownst to him, Cassidy is just outside the door but within earshot and, as he strides in, he explains that the market value is meaningless to him. He loves the works because they resonate with his having overcome a terrible childhood stammer, adding: “I like the reminder that they bring that I shouldn’t let a thing’s worth obscure its value.” The chastened critic is clearly embarrassed by the exchange, particularly in front of his newfound love interest.

Is the film as a whole a cynical take on the art world? Not exactly, says Capotondi. “It’s not a satire about the art world. I don’t want to look like I’m grandstanding. It should be fun to watch and carries a little message.” For instance, noting one of Figueras’s lectures in which the critic toys with an artist’s biographical details, he says: “It’s very easy to make something that’s a fake pass for something real if you know what to say or how to say it.”

At heart, he says, the film is a Faustian tale, but the art adds another layer, including questions about truth. “The art critic is obviously a key role here but it could have been anyone, a famous blogger or journalist. Obviously the fact that it’s set in the art world adds another layer, of beauty, and everything, including the dialogue is made more interesting because of it.”

“I really wanted to make a film that was fun to watch,” he said. “At the end of the day, it shouldn’t be taken too seriously.”