Art History

Art We Love: The Prickly Pleasures of an 18th-Century Caricature

On Philip Dawe's 'The Macaroni, a Real Character at the Late Masquerade' (1773).

On Philip Dawe's 'The Macaroni, a Real Character at the Late Masquerade' (1773).

Jo Lawson-Tancred

For an episode of the Art Angle podcast, we asked Artnet News writers and editors to tell us about one work of art that brings them joy. The following is a part of a series of transcripts of the answers. You can listen to the entire podcast on Apple Music, Spotify, or here.

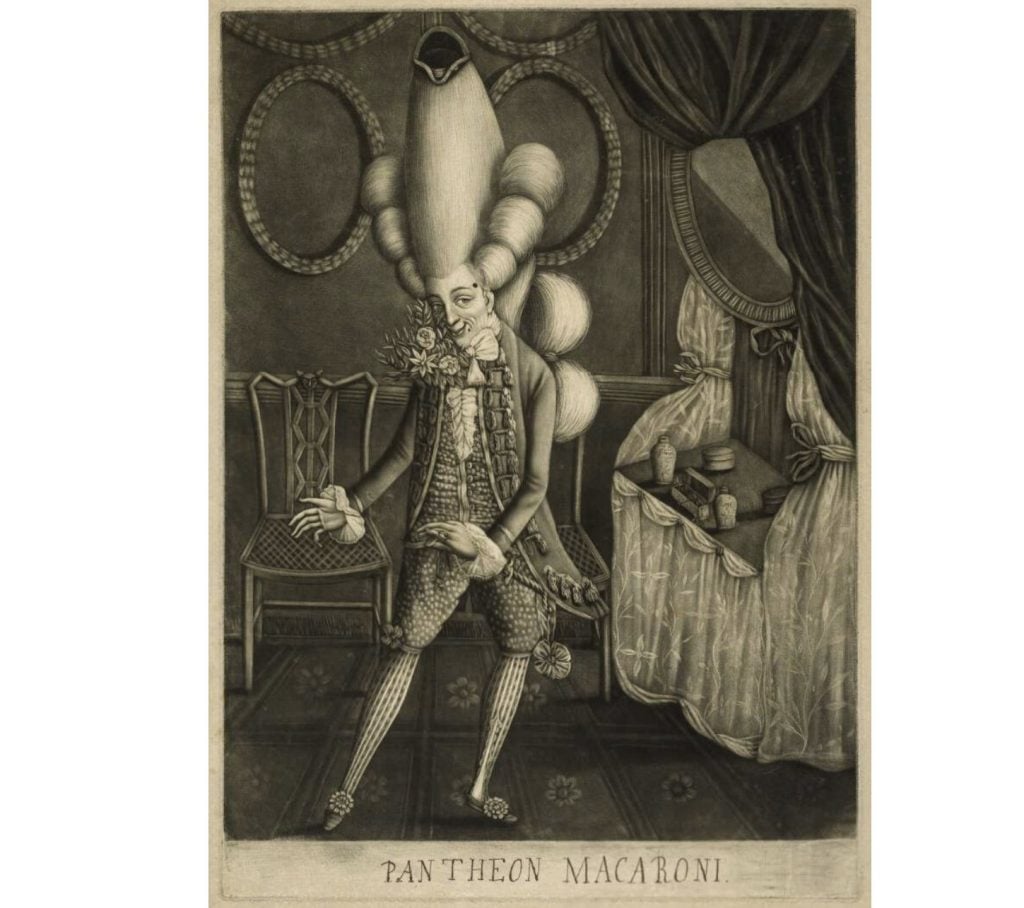

The work I picked is an 18th-century English caricature called The Macaroni, a Real Character at the Late Masquerade by a mezzotint engraver called Philip Dawe in the British Museum in London.

I can’t remember a time when I haven’t loved satirical prints from the 18th century, which is by far my favorite century. They never hold back when it comes to skewering their subject, and they speak to all the social anxieties of the day, some of which now feel absurdly outdated and others not so much. I love the historical insight—it feels much more human than a list of dates. And while it may not be very admirable, it’s entertaining to me that we are as fond of caricature satire today as we ever were.

The black-and-white cartoon from 1773 is of a man in a very fancy, elaborate outfit in a comically tall white wig with a tiny hat balanced on top. He’s in a very sumptuous interior next to a dressing table, and this furniture and the man’s delicately swaying, tiptoed pose heavily imply more stereotypically feminine attributes.

He looks right at us with a sort of smug, simpering smirk. The way he seems almost in on the joke and like he’s trying to provoke us, is what makes the image so engaging to me.

There were many prints like this one. The male figures were known as “macaroni,” a pejorative term, generally used to describe men who are usually upper class, extravagant in their spending, and excessively obsessed with fashion and appearances, probably quite affected, but perhaps also prone to gambling, spending all day at their gentleman’s club, dining and drinking and living the high life. Certainly, the perceived effeminacy of these men was usually highlighted, which obviously back then would’ve been seen as a bad thing.

It speaks to growing anxieties about class, consumerism, morality, and nationalism in Georgian England. Society was believed to be in a state of moral decline, and it was thought to be in the process of becoming far too superficial. At that time, wealthy young men were sent on opulent grand tours around Europe, and this print seems to imply that they would come back, if anything, overly cultured, too fashionable, and too influenced by Continental mannerisms.

There had been a long history of tension between France and England. In the 1770s, the Anglo-French war broke out. Some of the macaroni prints go so far as to imply that France was intentionally taking England’s strong, manly men and using the fashions of the day to turn them into defenseless, effeminate versions as a kind of military tactic of sabotage.

As someone who is all for effeminacy, it’s amusing to me that it would be considered such a threat to the nation. I delight in all the more frivolous aspects of 18th-century culture and love the idea of these overdressed, young aristocrats toppling out of a carriage and into the theater or heading off to a ball.

What brings me joy is the whole aesthetic of it. I should add that I can definitely see why, if I were living at that time, these characters would be much less endearing given how out of touch and entitled they must have seemed. Dawe’s work is a classic example of the genre of the macaroni print: every element is slightly exaggerated to comic effect, but I also think it just gets the balance right.

It never goes too over the top or becomes too ridiculous, which I think immediately ruins good satire, and there remains something believable about this character. You can imagine the viewers immediately recognizing him—perhaps they saw him occupy a box at the theater last night or strut by them on the street to get into their carriage.