Art World

Beyond the Golden Toilet: How Does Art End Up in the White House, and What Does It Tell Us About Our Leaders?

White House art loans have been in the pipeline for decades.

White House art loans have been in the pipeline for decades.

Menachem Wecker

It was the loan denial heard around the world. When the White House requested to borrow a painting by Vincent van Gogh from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in September, the museum’s chief curator Nancy Spector kindly declined, but countered with a hum-dinger of a replacement: a golden toilet by Maurizio Cattelan.

After the Washington Post reported the exchange late last month, many applauded her snarkiness, while others—including a Fox Business host who called for the curator’s resignation—viewed it as highly inappropriate.

Party-line divisions aside, the cause célèbre sheds light on a history of lesser-known art loans to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. And it illustrates how the Trump Administration appears to be doing things a bit differently than its predecessors.

A 1961 act of Congress formalized the White House’s art collection, which now contains about 65,000 objects, if one counts things like utensils and glasses individually. The collection also includes around 500 paintings. When a new president arrives, the White House curator’s office selects new works for display in public spaces and the West Wing.

The works can subtly communicate political priorities as well as personal tastes. President Ronald Reagan reportedly installed a portrait of Calvin Coolidge in the cabinet room as a nod to the importance of fiscal conservatism. When she was first lady, Hillary Clinton installed a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe in the Green Room. Michelle Obama acquired a bright abstract painting by Alma Thomas, which became the first work by a female African-American artist to enter the White House collection.

This photograph of the Family Dining Room was taken by Matthew D’Agostino on July 27, 2016. Among the selected pieces of work was “Resurrection” by Alma Thomas, seen on the north wall.

A new first family can also request art to decorate private spaces. Two paintings by Edward Hopper, for example, hung in the Oval Office during Obama’s final term, on loan from the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

“The Bushes opted for traditional landscapes, various Impressionist works, and historic etchings that were framed,” said Matthew Costello, the senior historian at the White House Historical Association. “The Obamas preferred a much more modern motif in the family quarters, changing the paint color and adding large pieces of modern art throughout the central hall. This also carried over to the family dining room on the state floor, where the Obamas changed the décor to reflect their modern tastes.”

So far, the Trump Administration’s requests have not followed traditional protocol. Normally, the president’s office will request a number of loans from the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. But a year into Trump’s tenure, neither institution has received a request for loans to decorate the presidential office or residence, according to spokespeople.

The White House didn’t respond to multiple interview requests, so the question remains why it sought to borrow the Guggenheim’s Van Gogh before issuing requests to museums closer to home, with which the White House has prior loan programs. (The Van Gogh painting, Landscape with Snow [1888], depicts a man in a black hat walking through a field with a dog.)

Vincent van Gogh’s Landscape in the Snow (1888), which Trump requested to borrow from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

The National Gallery has lent hundreds of artworks to the White House since 1945, according to a spokeswoman, and loans often extend through multiple administrations. White House curators and decorators typically visit the gallery and share what kinds of work interest their bosses.

Both the president’s and vice president’s offices have visited the National Gallery, so it is possible that loans will be forthcoming. (Karen Pence, the wife of Vice President Mike Pence, also visited in person.) The request process is typically complicated and long, said the gallery spokeswoman.

Gallery guidelines prohibit removing objects that are on view or undergoing conservation. Works that are covered by existing loan agreements or already slated for exhibition are also off the table. Certain works, like the Chester Dale Collection, can’t ever leave the gallery.

The Smithsonian Institution has also lent work to the White House for decades, according to its chief spokeswoman. Registrars at individual Smithsonian museums typically work with the requester. “We loan to the White House—public and residence—cabinet, Supreme Court, DC mayor, and other high-ranking officials,” she said.

First Lady Michelle Obama talks with Director and Chief Curator Thelma Golden during a tour of the Studio Museum in Harlem, in New York, N.Y., Sept. 21, 2011. Official White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy.

According to a list provided by the Smithsonian, current loans include nearly 30 paintings to members of Congress, two to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, nearly 45 paintings (including several Hudson River School canvases) to the Supreme Court, and 17 canvases to the White House, including Camp David. None of the White House loans began after Trump’s election, according to the document.

Some say that the White House—an historic building of epic significance—should borrow objects only insofar as they enhance its historic context. That makes a painting by a Dutch painter an unorthodox pick. “Van Gogh, while an amazing artist, is not necessarily an obvious choice for the American-based, historical setting that is dedicated to the business of our nation,” said a former art museum director who asked not to be named.

Costello—the senior historian for a private nonprofit that helps the White House acquire, preserve, research, and educate the public about its collection—sees things differently. “I think it speaks to the idea that the White House is a ‘living museum,’” he said.

Robert Rauschenberg’s Early Bloomer [Anagram (a Pun)] , silverware, and an early NewEngland sideboard once owned by Daniel Webster in the White House residence. Photo: Matthew D’Agostino, 2016.

“Certainly, more people would be able to see a prized piece of artwork here than if it stayed in a gallery at a smaller museum or repository,” he added. (That would only apply, of course, to works installed in the parts of the White House that are open to public tours.)

Had the Guggenheim agreed to send the Van Gogh picture, it wouldn’t have been the first institution beyond the National Gallery and the Smithsonian to lend to the White House. Over the past 75 years, a wide variety of institutions have offered up work—often by American artists—for a range of purposes.

In 1965, the Dallas Museum of Art sent Jackson Pollock’s Cathedral (1947) to DC as part of President Johnson’s White House Festival of the Arts Foundation. Thirty years later, President Clinton requested Scott Burton’s minimal sculpture Granite Settee (1982–3) for the exhibition “Twentieth Century American Sculpture at the White House,” held from 1994 to 1996.

More recently, the New-York Historical Society sent Thomas Hill’s View of the Yosemite Valley (1865) to hang above the head table at President Obama’s inaugural luncheon on his first day in office in 2009. The piece, noted the event website, “reflects the majestic landscape of the American West and the dawn of a new era” and depicts the hope and inspiration that many Americans sought in the West as “the country struggled to emerge from the turmoil of the Civil War.”

Thomas Hill’s View of Yosemite Valley (1865). Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

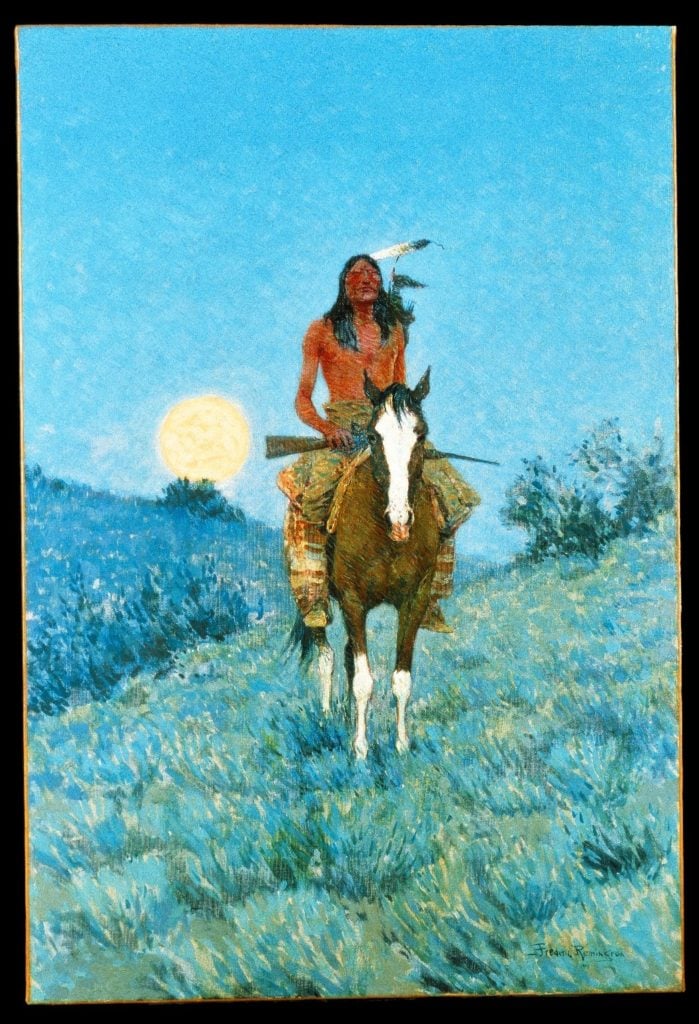

Between 1996 to 2010, the Brooklyn Museum loaned four works to the White House, including Frederic Remington’s The Outlier (1909), John Frederick Peto’s Door with Lanterns (late 1880s) for the West Wing reception room, and Robert Lobe’s Harmony Ridge #26 (1990), lent for an exhibition of 20th-century American sculpture.

In 2004, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, sent Edward Wilbur Dean Hamilton’s Summer at Campobello, New Brunswick (c. 1900) the White House. In 2014, the museum received another White House request—for a 3D printed Iris Van Herpen dress for a one-day education workshop—but the request was later canceled.

The Walker Art Center, meanwhile, loaned George Segal’s bronze Walking Man (1988) for the exhibition “Statues into Sculpture” in the first lady’s garden from 1994 to 1995.

Frederic Remington’s The Outlier (1909). The work was on loan to the White House from from Aug. 14 1996 until Aug. 31, 2010. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Some senators also borrow from their hometown museums. Roy Blunt, a Republican from Missouri, has two Thomas Hart Benton paintings in his DC office on loan from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. Former Missouri House member Ike Skelton also borrowed from the Nelson-Atkins for his office.

Occasionally, White House loans can get dicey, according to the White House Historical Association’s Costello. In 1969, when President Nixon requested that the Frederic Remington Art Museum lend Remington’s Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill (1898) to hang in the Roosevelt Room in the West Wing, the New York museum agreed, but only for two years.

“The work was returned to the museum, even though Nixon wanted to keep it in the West Wing beyond the loan,” Costello said.

The history of the work itself is tied to world affairs. When Remington cabled William Randolph Hearst from Cuba saying that there was no war for him to illustrate, the latter was said to have replied, “You furnish the pictures. I’ll furnish the war.” Much has changed since the Spanish American War. Evidently, today’s clarion call is: We can’t furnish the painting, but would a golden toilet do the trick?