Art World

Never Mind the Great Rap Feud—Here Are 4 Scathing Art-World Beefs

Sorry, no diss tracks included, but these disputes still bring the venom.

The diss tracks flying back and forth between Drake and Kendrick Lamar have set the online and offline world aflame. But rappers aren’t the only creative people who get into serious disputes. All throughout history—as Artnet News’s Jo Lawson-Tancred wrote on the occasion of the great “Degas/Manet” exhibition of two artist-frenemies at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art last year—there have always been conflicts between artists: Gauguin and Van Gogh, Leonardo and Michelangelo, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud.

Those conflicts have continued to this very day, with, just as one example, Anthony James recently lobbing charges of copying at Maurizio Cattelan.

Here are four more beefs between art-world honchos, spanning from the ‘50s to the aughts, that are, regardless of when they took place, truly for the ages.

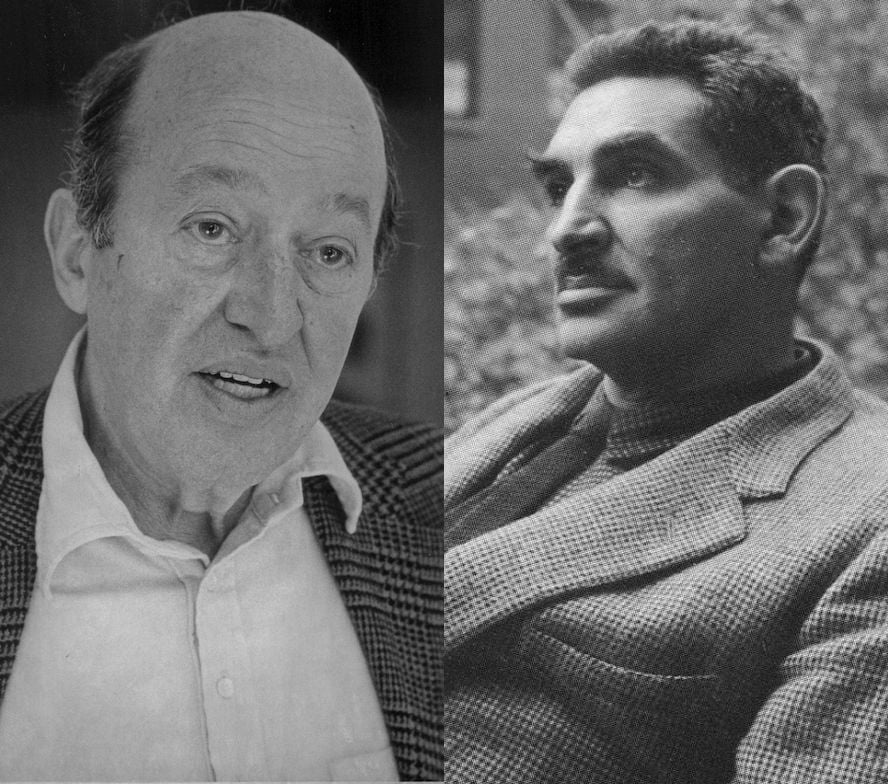

Clement Greenberg v. Harold Rosenberg

Left: Clement Greenberg (1977). Photo by Kenn Bisio for the Denver Post via Getty Images. Right: Harold Rosenberg. Photo by Maurice Berezov for A.E. Artworks, collection of the Jewish Museum, New York.

The physical brawls between the Abstract Expressionist artists at New York’s Cedar Tavern are legendary, but at least two critics were in on the conflict, too. Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg may not have come to blows in public (though they are rumored to have nearly done so in private), but they took real jabs at each other in print over differing critical positions.

The fracas dates at least as far back as Rosenberg’s 1952 ARTnews essay “The American Action Painters,” in which he wrote that artists were treating the canvas as an “arena in which to act,” saying: “What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.” Employing a sobriquet used by British critics, Greenberg responded with the 1955 Partisan Review essay “‘American-Type’ Painting,” in which he put forth his trademark position that painting should progress toward its own essence, defined by flatness. No events for Greenberg! Rosenberg saw the subjective and mythical in painting, but Greenberg felt that everything “literary” must be excised.

They sniped at each other even in the titles of their essays. Greenberg had his opposite number in mind when in 1962 he published “How Art Writing Earns Its Bad Name”; in 1963, Rosenberg returned to the pages of ARTnews, where he responded with “Action Painting: A Decade of Distortion,” calling his rival (egad!) academic.

Donald Judd v. Dia Art Foundation

Headquarters building of the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith / Buyenlarge / Getty Images.

The Dia Art Foundation today is highly respected as a staunch supporter of large-scale, non-commercial art projects, including Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field, Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. But all has not always gone smoothly inside the institution’s hallowed halls.

Sculptor Donald Judd put up his dukes against the Foundation in 1985, when he threatened a lawsuit against the art patrons for, as he saw it, reneging on a contract the institution had signed in 1979. By 1985, Dia had spent some $3 million supporting Judd’s now-legendary project in Marfa, Texas, where he bought 340 acres of land and former army barracks and warehouses and turned them into a showcase for his own Minimalist art as well as examples by John Chamberlain and Dan Flavin.

But when the foundation fell on hard times in the mid-’80s because its investments dipped due to a steep drop the price of oil (where much of its money was parked) and the organization tried to sell off some of the works installed in Marfa, Judd threatened to sue.

”We… agreed that the artworks… would be available for public viewing, and that they would never be moved,” Judd told the New York Times, which pointed out that though the contract had expired in 1984, Judd held that Dia had “reneged” on some of its provisions.

”We have evaluated Judd’s claims, and do not think a lawsuit is justified or well-founded,” Dia’s lawyer fired back. “As far as we are concerned, we have fulfilled our side.”

In the end, the case was settled out of court and Judd won control of the property, which he reopened in 1986, rechristened as the Chinati Foundation. And thank goodness: it remains a pilgrimage site for art-lovers, scholars, and Minimalism freaks to this day.

Rosalind Krauss v. John Richardson et al.

Rosalind Krauss photographed by Judy Olausen circa 1978. Photo: via Art Critical.

Just as art writers can disagree on the works of their contemporaries, of course, the knives can come out when art historians, critics, and theorists evaluate their colleagues’ analysis of historical figures. In one art such feud, October magazine cofounder Rosalind Krauss went after Picasso experts Mary Mathews Gedo, John Richardson, and William Rubin in her bristling essay “In the Name of Picasso,” included in her landmark 1986 book The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths.

She pointed out that in a 1980 lecture, Rubin, also director of the painting and sculpture department at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, presented two of the master’s Cubist paintings of women that are stylistically similar (she called them “nearly twins”), but said that they were starkly different because of biographical concerns: one was inspired by his wife, Olga, while the other was based on his lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter.

Sir John Richardson. Photo: BFA

Here, she wrote with icy disdain, “we run fill tilt into the Autobiographical Picasso,” an art-historical mode that eschews “style, social and economic context, archive, [and] structure.” A huge Picasso retrospective at MoMA, she complained, included a flood of art history fueled by “Art as Autobiography.” She said the approach reaches “delicious, unintended parody” in the scholarship of Gedo.

But the villain behind all this, looming over people like Rubin and Gedo and in fact seducing them away from previous art-historical modes, she wrote, is another Picasso expert, John Richardson (who would go on to write a massive biography of the Spaniard). Reviewing the show, she wrote, he took the same tack by arguing, in her summation, “Picasso’s art is at any one time a function of the changes in five private forces—his mistress, his house, his poet, his set of admirers, his dog (yes, dog!).” Woof!

Robert Storr v. Okwui Enwezor et al.

Robert Storr. Image: Alberto Pizzoli/AFP/Getty Images.

Curator Robert Storr’s 2007 Venice Biennale gave rise to one of the most searing exchanges among critics in recent memory, all playing out in the letters pages of Artforum (a magazine more recently known as much as the subject for debate than the site thereof).

“Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind: Art in the Present Tense” gave rise to a fairly unhinged and at times stunningly personal exchange of missives, which would be too many to even try to sum up thoroughly here, so we’ll just give you a few of the lowlights.

In a 4,180-word review, curator Okwui Enwezor dubbed Storr’s show “a punishing exercise in revanchist melancholia.” Jessica Morgan, then curator of contemporary art at Tate (now Dia Art Foundation director), weighed in at about 2,000 words, calling Storr’s title “cringe-inducing” and pretty much dismissing him as an organizer of groundbreaking exhibitions or a discoverer of artists, or as one with “anything like a global perspective.”

Okwui Enwezor. Photo: Joerg Koch/Getty Images.

At a door-stopping length of 8,800 words, Storr fired back in the September 2007 issue, leading off with the stage-setting assertion that “all of the reviews of the Biennale in Artforum—except for the thoughtful treatment by Katy Siegel—were blindingly ad hominem.”

“Jessica Morgan leads the pack,” he said. Responding to her dismissal of his title, he brands the titles of her books (Chic Clicks; Common Wealth; Time Zones; Pulse: Art, Healing, and Transformation) as “boldly idea-lite.” She dismisses him as a curator, he said; he defends himself in epic style, branding her petty along the way and speculating that maybe her attack was an audition to curate a biennial of her own. Enwezor, in Storr’s view, exhibited an “arrogant and dissembling belligerence.” Curator Francesco Bonami’s response, meanwhile, he called “utterly bizarre and at times inadvertently hilarious,” and said his embarrassingly critiques of the Biennale are “replete with half-truths, blatant untruths, and nonsensical fictions.” The Italian had made so many critiques of the show in so many venues, he concluded, that he “has become my stalker.”

Jessica Morgan: Director of the Dia Art Foundation in New York. Photo: Getty.

And it just went on (and on, and on, and on) from there, as the combatants lobbed bombs at each other in subsequent issues. Love a feud? Get on eBay, order yourself up some back copies, and put on a pot of coffee, because you may be up all night.