Artists

Earth Art Pioneer Alan Sonfist on Galvanizing a New Generation of Land Artists

A key figure of the environmental art movement addresses the fragility of our natural world.

A key figure of the environmental art movement addresses the fragility of our natural world.

Dian Parker

The natural world is not an artifact, but a living, breathing entity that is at the root and center of our human existence. Throughout the centuries, people have treated nature as a perpetual commodity, but we now know that many of the Earth’s resources are disappearing at an alarming rate. This is a global crisis and one that Alan Sonfist, an environmental artist, has been addressing for a lifetime.

In a wide-ranging interview, Sonfist discussed his decades-long effort to reconnect humans to the environments we live in and to call attention to nature’s fragility in the face of destruction. “It is through my art that I can create an awareness of the archeology of these natural systems,” Sonfist said.

Born in 1946 in the Bronx, Sonfist played as a child in the neighborhood hemlock forest, where, he recalled, “my mother first put me into the hollow of a tree before I could walk.” Later, he saw much of the ancient old-growth forest being ruined by fire and garbage. Today, it has “been improved” outwardly, but risks becoming “merely ornamental.” His own artistic vocation grew as a result of the wildness and sense of wonder he experienced in the forest of his childhood.

Artist Alan Sonfist. Courtesy of Alan Sonfist Studio.

A pioneer of ecological works since the late 1960s, Sonfist has yet to receive the level of critical attention given to contemporaries from the land art movement. In fact, he has always followed a different path from the heroic landscape interventions most associated with the movement in the United States. “I don’t want my artwork to alter the land but to bring it back,” he said. He has spent his adult life investigating and replanting Indigenous flora through his trailblazing “time landscapes” and other projects around the world.

The hemlock forest in the Bronx taught Sonfist a formative lesson. “I realized how humans were hostile to this jewel within the city. I decided that it was time to share the unique experience of an ancient forest within an urban setting with the community.”

It took Sonfist 13 years to realize the first Time Landscape in New York City. After endless meetings with expert scientists, politicians, urban planners, and community members, he finally convinced city authorities to give him a rectangular plot of 25 by 40 feet in Lower Manhattan.

“The precedent in urban planning at that time was that forests belonged outside of cities and that cities were places of concrete,” Sonfist said. “I wanted to lift up the concrete and reveal the nature that had been there before European colonization.” He researched the ancient forests of New York from old maps in the public library collections and worked with volunteers to rewild the area with native trees, shrubs, grasses, flowers, plants, rocks, and earth.

The plan Sonfist created in 1965 for the first Time Landscape, in a corner of New York’s Greenwich Village. Courtesy of Alan Sonfist Studio.

An essay Sonfist wrote in 1968, aged 22, laid out a manifesto. “Public monuments traditionally have celebrated events in human history—acts of heroism important to the human community. Increasingly, as we come to understand our dependence on nature, the concept of community expands to include non-human elements,” he wrote. “Especially within the city, public monuments should recapture and revitalize the history of the natural environment at that location. As in war monuments, that record of life and death of soldiers, the life and death of natural phenomena such as rivers, springs, and natural outcroppings needs to be remembered.”

Fifty-plus years later, Sonfist’s hard-won Time Landscape continues to grow in Greenwich Village, at the corner of LaGuardia Place and West Houston Street. A local resident reports that it is a beloved respite in the city. Bowls of water are left for the birds and squirrels, branches arc over the iron fence to shade the sidewalks, flowers bloom, and insects pollinate.

Alan Sonfist’s first Time Landscape, photographed today. Courtesy of Alan Sonfist Studio.

The artist’s ecological message seems more timely now than ever, noted Adam Weinberg, the director emeritus of the Whitney Museum of American Art. “Since the ’60s, [Sonfist has] continued to push forward his ideas about the land, particularly urgent right now with global warming all over the world. We need solutions to climate change not only from scientists and politicians but also from artists, envisioning and realizing a greener, more primordial future.”

Sonfist has long worked in tandem with scientists and politicians, as well as private patrons, to make his ambitious environmental installations a reality. Commissioned by Prince Richard of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg, Sonfist created Lost Falcon of Westphalia on the German prince’s estate in 2004. He reinstated plant species that had once been native to the forests there on Celtic-style mounds, tracing the form of a falcon only visible from a bird’s eye view. “I had to work with genetic scientists to find the prehistoric trees from 12,000 years ago, before the last Ice Age,” Sonfist said, such as the ginkgo, “the oldest tree on Earth.”

As the seasons change, Sonfist’s Lost Falcon of Westphalia stands out like an amber arrow among the rolling German hills of evergreens. Photos courtesy of Alan Sonfist Studio.

He received another commission from the city of Florence in 2011, Ancient Olive Grove of Athena. Sonfist discovered there were no longer any ancient olive trees still living in Italy; the species had migrated to Morocco. Replanting these trees in Florence entailed another act of migration and adaptation, so “they have to live in the fabric of the city now, to naturalize in this environment,” he said.

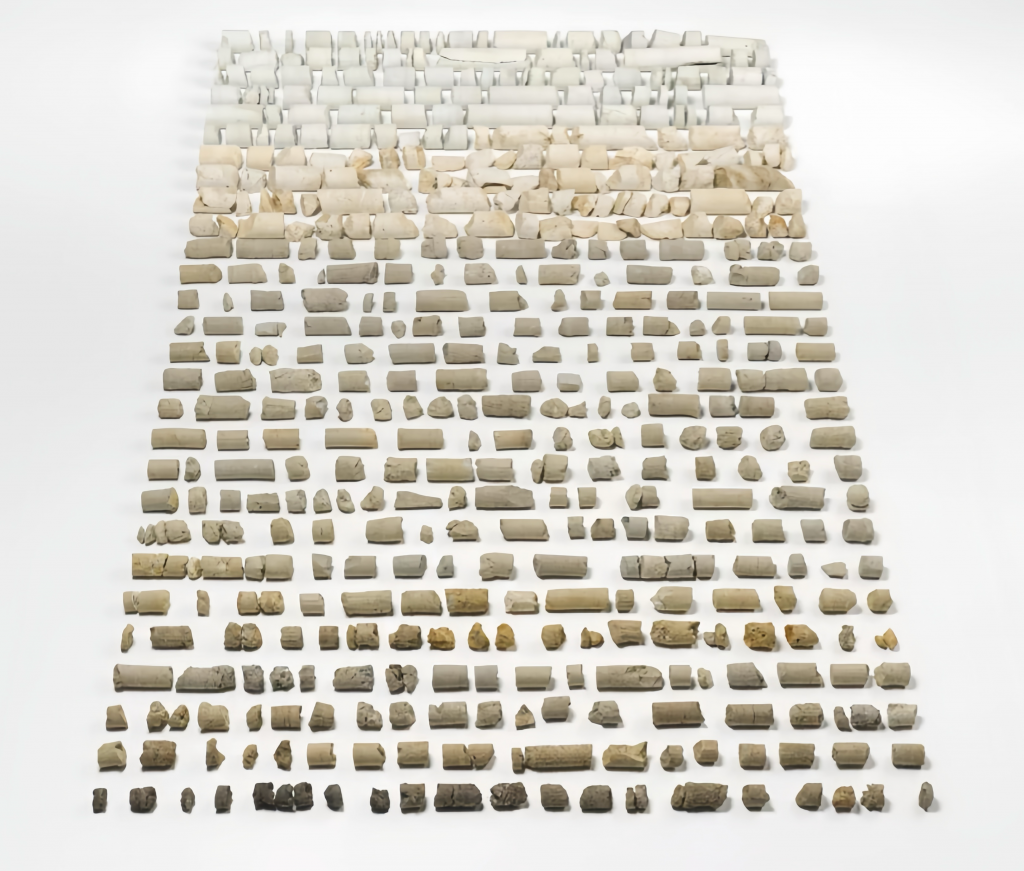

Although Sonfist is best known for his large-scale outdoor projects working directly with nature as his medium, he has spent decades evolving his ideas through collages, drawings, paintings, and smaller sculptures. His minimalist sculpture series, Earth Monuments, assembles cylindrical earth drillings from the substrata of rock beneath various cities. Each work amounts to a geological history of a place, revealing subtle variations of color and texture in the layers of the land.

Alan Sonfist, Earth Monument to Chicago (1971). Visualization of earth beneath the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Courtesy of Alan Sonfist Studio.

In Burning Forest, a more recent series of paintings, Sonfist depicts trees selected from the majestic 19th-century landscapes of his “heroes,” the Hudson River School artists. Sonfist disrupts their visions of America’s pristine natural beauty, however, by setting the trees on fire to visually represent the climate crisis. He continues to work on this series to this day.

The artist is currently preparing one of his signature site-specific projects for a climate-themed exhibition, titled “Celestial Landscape,” slated for 2026 at the Parrish Art Museum in the Hamptons. “Parrish Celestial Meadow of Indigenous Plants is what he calls a poetic universe,” said the museum’s chief curator of art and education, Corinne Erni. Sonfist will fill a circular plot in the museum’s south meadows with wildflowers and grasses in a configuration that reflects the constellations of the stars above.

“A star’s movement can be identified by its color changes from warm blues to vibrant yellows and reds. Similarly, the circles of planted wildflowers will have a range of hues that identify the stars above them. Native wildflowers will be planted with colors that resemble the colors in the cosmos,” Erni explained. Sonfist’s drawings of the plants and the stars will be installed inside the museum along with a continuous video projection of the meadow—an invitation to audiences to “observe the process of growth” and, perhaps, to share a measure of the artist’s reverence for the natural world.

Alan Sonfist, American Earth Landscape (2019-2021). Primal earth sealed on canvas. Courtesy of Alan Sonfist Studio.

Now in his late 70s, Sonfist hopes he can galvanize a new generation to take forward his legacy of art entwined with ecology. “The undercurrent of my art has always been how we are connected to the environment and our impact on it,” he said. His acute awareness of the deepening climate crisis led him to create an initiative called Land Art Forward—“a new dialogue, helping young artists and scientists work together to address this threat to humanity.” The budding alliance launched last year with a symposium organized by the Art, Culture, and Technology program at MIT, and has found supporters in Asia and the Middle East.

“All great art addresses the issues of its time,” Sonfist said, “and the greatest issue of our time is the climate crisis.”