Growing up in western Pennsylvania, Alicia Adamerovich had a deep affection for the forests that surrounded her family home; after all, her father built their house using wood and rocks he found there. “We lived far from other people,” said the artist, who now resides in New York City, from her Ridgewood, Queens studio. “This is the farthest I’ve lived from nature.” Still, she said, “I’m drawn to it—and to the practice of using what’s available.”

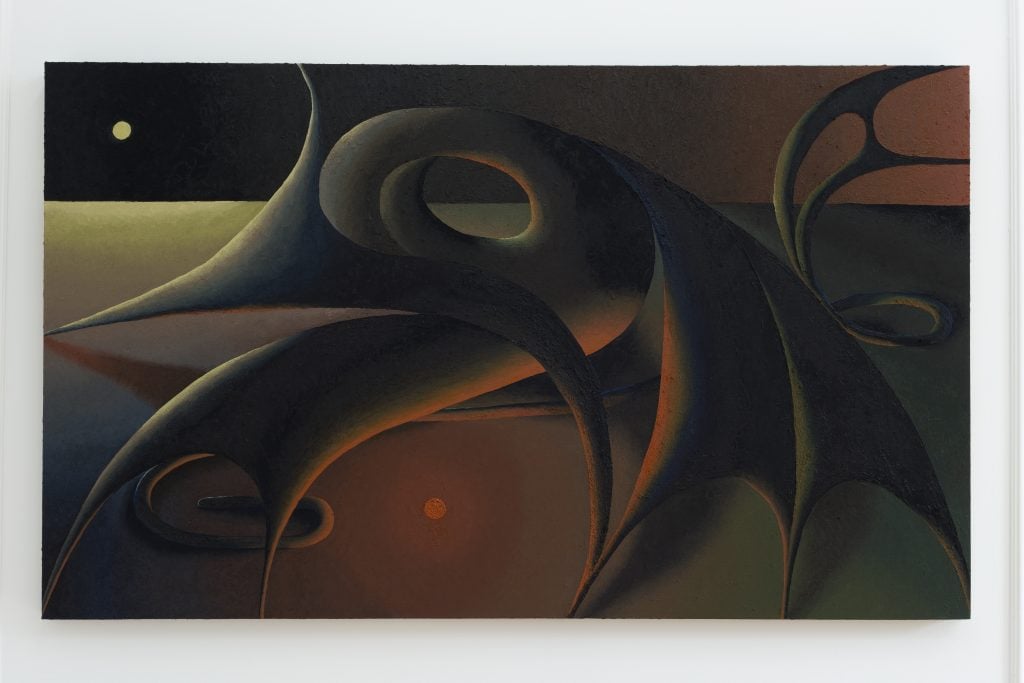

Adamerovich’s affinity for nature—its majestic wonders as well as its grisly terrors—manifests in the organic, anthropomorphic forms and alien, moonlit landscapes of her ghostly paintings and sculptures. “These forms represent thoughts and feelings,” she explained. “I’m not trying to remake anything from our physical world; everything I’m making is psychological.”

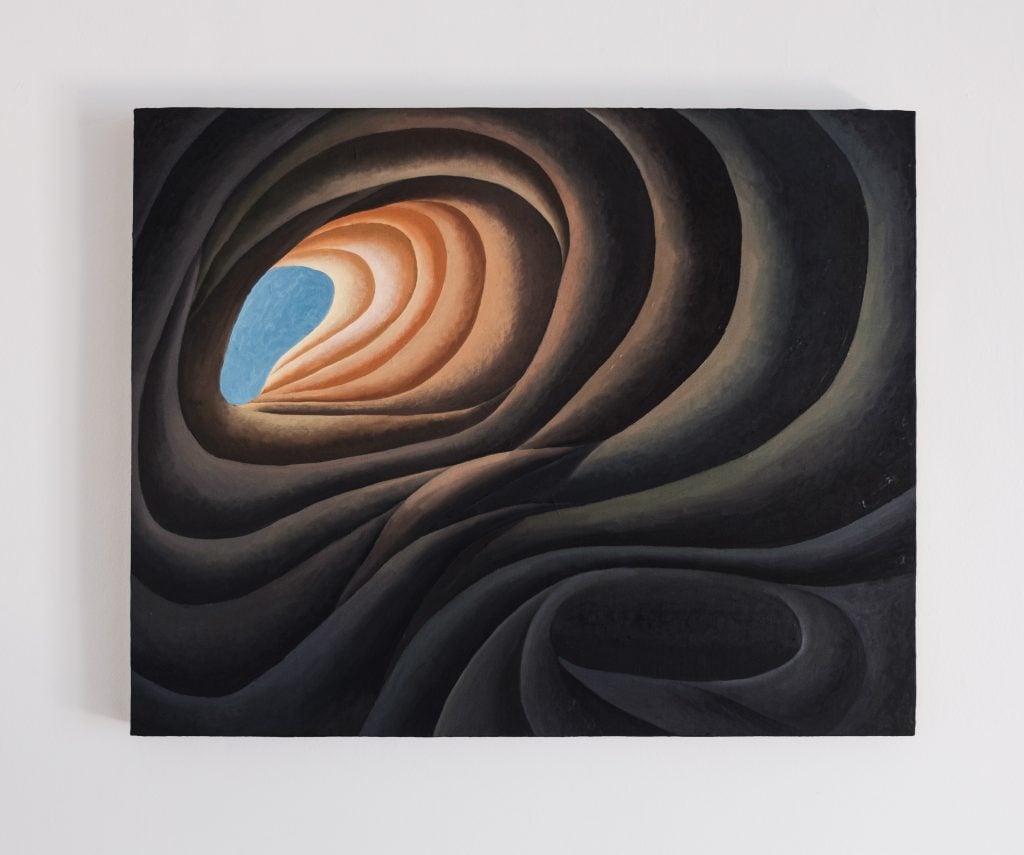

Alicia Adamerovich, Thursday’s Child, (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Del Vaz Projects.

Recalling the spiritual abstractions of artists such as Hilma af Klint and Agnes Pelton, which have recently seen renewed interest, Adamerovich’s biomorphic forms offer an entry point into mysticism and intuitive wanderings as well as a space for personal contemplation, whether inspired by the natural world or—in the Surrealist tradition—her weekly therapy sessions.

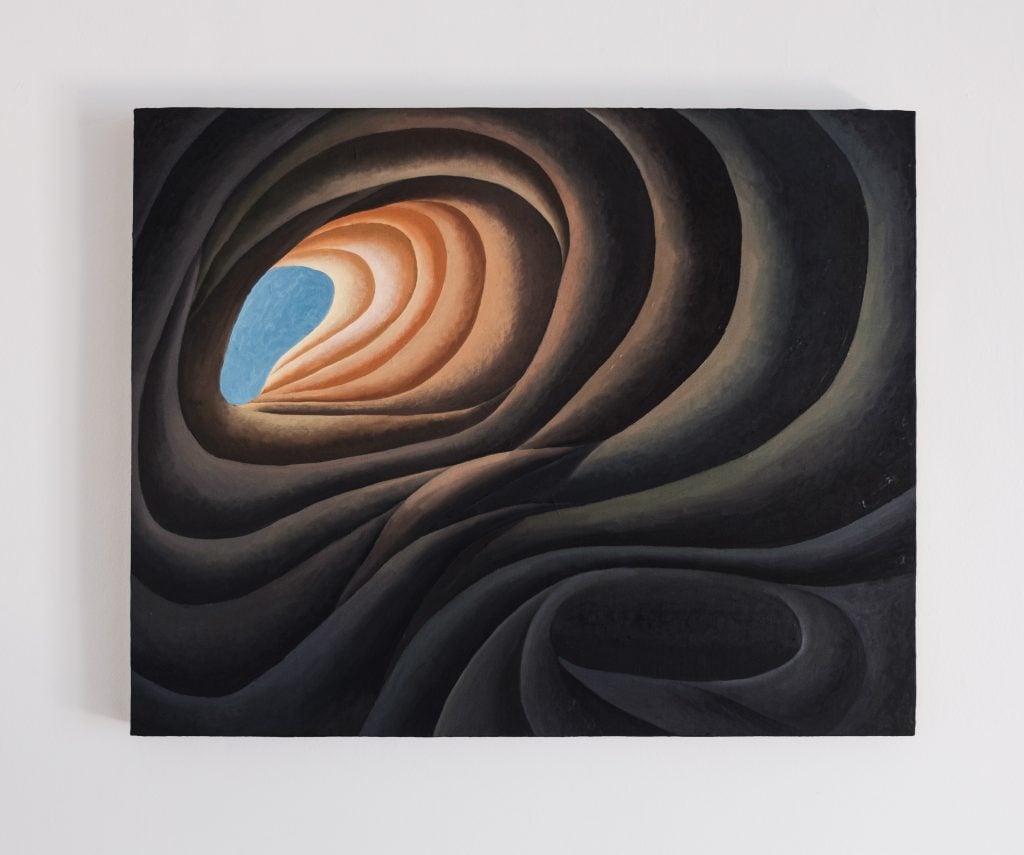

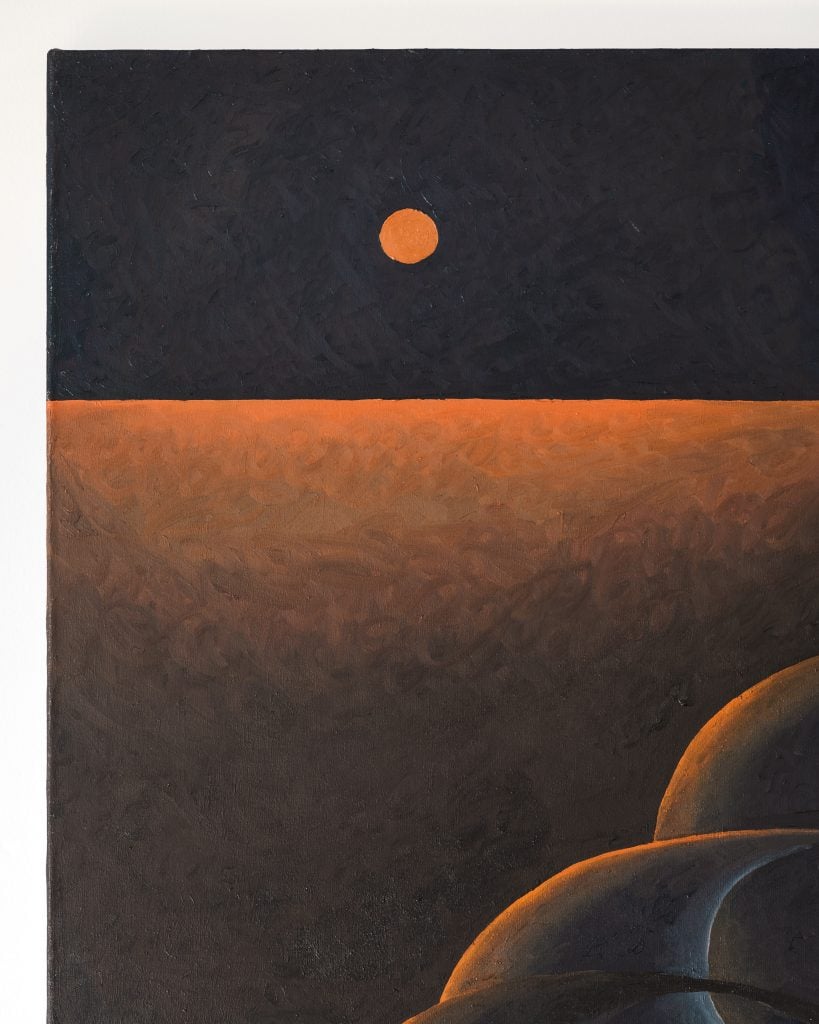

Take Genesis (2021): the wall work resembles a Rorschach test, with overlapping layers of wood carved into what appear to be smoothed-down segments of throwing stars or autumn leaves. They stack up to create little caves that contain cutouts for two small paintings—one of a full moon lighting up a raven sky, the other a miniature detail of her large-scale painting Thursday’s Child (2021), in which a sequence of plump, chalky ovals with tails evolves from a tiny sphere, almost like a lunar cycle.

Alicia Adamerovich, Genesis (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Del Vaz Projects.

Adamerovich has a small woodshop in the middle of her studio, where she makes the spindly, spiraling frames and standalone sculptures that, alternately varnished and shaded by singeing, are carved from trees that have died and fallen on her parents’ land. She begins with a single branch, then adds to it until the shape begins to resemble the subject of the image it’s framing.

The artist takes the opposite approach for her canvases, subtracting instead of adding darkness; she begins each one with a black surface and paints in several layers of light. Adamerovich attributes this styling to her love not only of nature, but also of film, where lighting can be designed to create drama and character. “I like seeing emotion created through landscape,” she said.

“We love the evolution of Alicia’s practice,” said Raphaëlle Cormier of Pangée, the artist’s gallery in Montreal, where Adamerovich’s first show exhibited her drawings within sculptural, hand-carved wood frames. “Since then, she has been blurring the lines between her bidimensional and sculptural works more and more.”

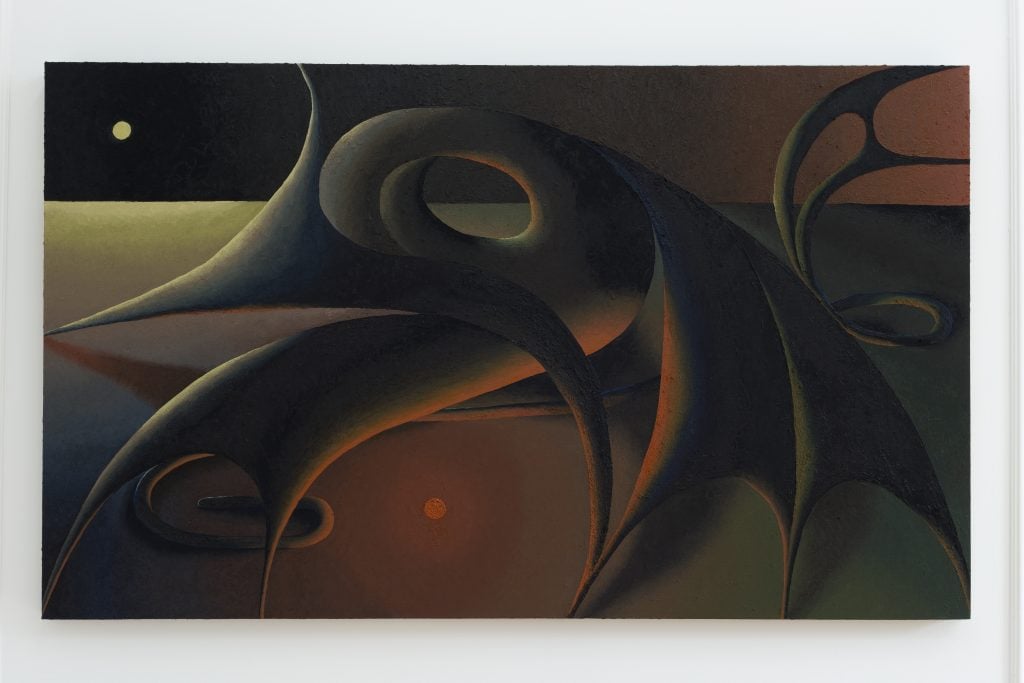

Alicia Adamerovich, Untitled (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Del Vaz Projects.

Following her recent exhibitions at Pangée as well as Del Vaz Projects in Los Angeles—not to mention presentations at Yee Society in Hong Kong, FISK Gallery in Portland, Sans Titre in Paris, Galerie Tator in Lyon, and Margot Samel in New York—plus a string of sold-out shows and acquisitions by institutions such as the He Art Museum in Guangdong, China, the intensifying demand for Adamerovich’s works has them selling for up to $50,000 each.

The artist is now represented by Kohn Gallery in Los Angeles, where she’s set to have her debut show next January; a group show at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris and a presentation at Art Basel Miami Beach are also forthcoming.

Alicia Adamerovich, Untitled (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Del Vaz Projects.

“Alicia’s visual vernacular is unlike anything we’ve shown before, both technically and symbolically,” said Joshua Friedman, a partner of Kohn Gallery. “She is truly distinctive in the way that she depicts foreign yet familiar emotions. Her introspective journey into the human subconscious resonates in a cathartic manner.”

For “Second Nature,” her show of paintings, drawings, sculptures, and paintings in sculptural frames at L.A.’s Del Vaz Projects in the fall of 2021, Adamerovich turned up the contrast and perspective, making every image feel more distant than the previous one—as if she shined a bright flashlight into a realm one dimension away from where her other works reside.

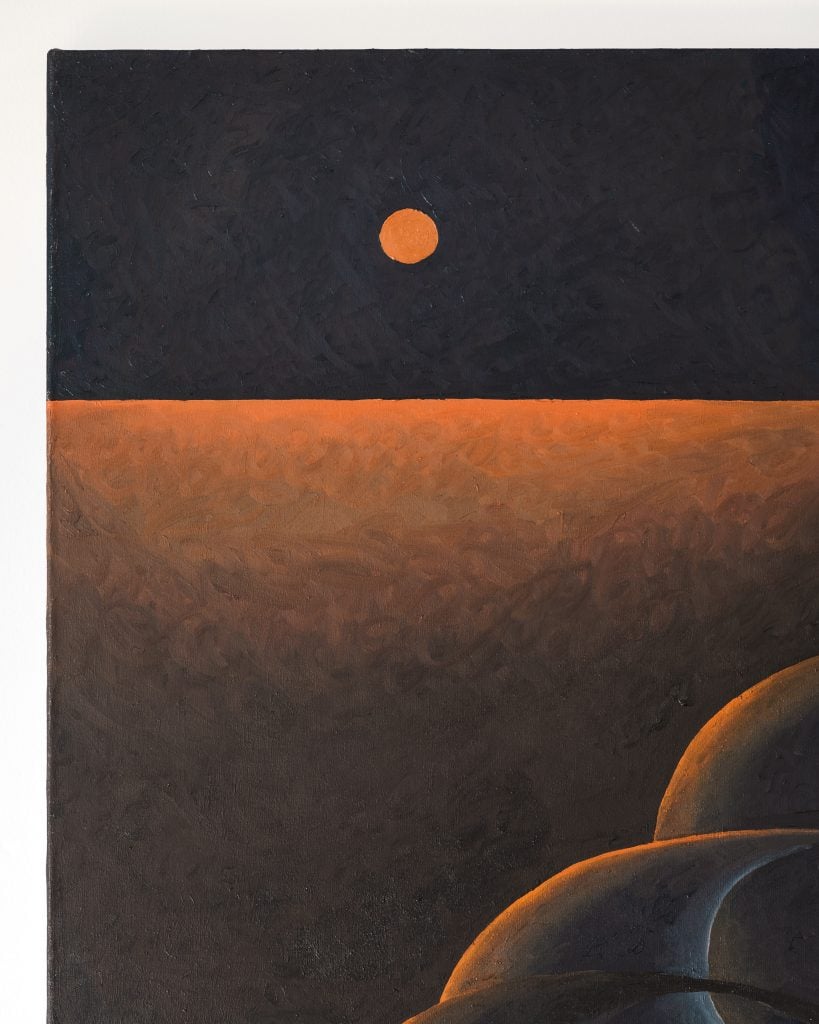

Alicia Adamerovich, The cradling glow (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Projet Pangée.

Meanwhile, for Pangée’s recent exhibition “Ultra-gentle manipulation of delicate structures,” the artist’s paintings introduced eggshell-smooth, interlocking vessels covered in sand balancing on hairpin-like legs in near darkness, apart from a single, unseen light source. The silky curves in her framed works echoed the carved objects resting on the floor, reflecting the hypnotic lines of channels and tunnels back and forth to each other. “I was exploring the crossover between very delicate, fragile things and the strength in protective forms,” the artist said.

“Alicia really impressed me with her obstinacy to make dreams come true, literally,” said Joël Riff, an independent curator at La Verrière for Fondation d’entreprise Hermès in Brussels and at Moly-Sabata for Fondation Albert Gleizes in Sablons, France, where the artist was in residence in 2021. “Her work is about the legacy of Surrealism as well as her appetite to do things by herself. She’s always experimenting with new techniques in order to give materiality to her most ethereal visions”—even learning crafts from online tutorials, he noted.

Alicia Adamerovich, Thursday’s Child (detail; 2021). Courtesy of the artist and Del Vaz Projects.

For her upcoming exhibition at Kohn, Adamerovich has been exploring her enchantment with a recurring presence in her practice—the horn, both as a shape and as a concept. Her new works embody all the ways in which the form is a physical articulation of force and amplification. “I can feel overwhelmed while also scared, excited, happy, amused, or out of control,” the artist said. “To me, the horn is a loud sensation, and so far, the work is heading in a visually louder and more absurd direction.

“Everything I work on is a continuation, in that I start with something that I started touching on in the previous show, but I also work on an entire show at once—as one thought, in a way.” The artist’s created world seems to grow deeper instead of taller, excavating a universe rather than constructing one. The horn has always been a tool for megaphoning and long-distance communication—and Adamerovich’s art traverses realms.