People

Artist Cornelia Parker on How Politics Influences Her Art, and Why She Doesn’t Sell to Private Collectors

The artist is currently the subject of a retrospective at Tate Britain.

The artist is currently the subject of a retrospective at Tate Britain.

Amah-Rose Abrams

Cornelia Parker’s work has been described as “violent,” and it’s not hard to see why. She has blown up a shed, thrown things off cliffs, steamrolled musical instruments, and painted with a lethal poison.

The artist does not shy away from the difficult or the strange. In fact, she zeroes in on these areas of life, sometimes dissecting them, sometimes reconfiguring their parts. She looked, for example, at the 2017 snap election in the U.K., which led to Brexit, and saw a country seemingly disassembling itself. That theme appeared in her later film Flag (2022), where she takes apart a Union Jack.

Her process, both investigative and instinctive, has led her to soak starched cocaine out of smugglers clothes and wrap Rodin’s Kiss in a mile of string. Her practice gained momentum through the 1990s and 2000s, and today she has earned her place as one of the U.K.’s most beloved artists.

We caught up with Parker just after the opening of her Tate Britain retrospective, on view through October 16.

Cornelia Parker, Perpetual Canon (2007). Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London © Cornelia Parker.

Where does an idea start for you and how do you know what its final form will be?

I think I collect fragments towards an idea over a long period of time and then it gets to a point where it has to be made. The greenhouse piece, Island, at the end of the show, for example, had been an idea for a long time and it gradually worked its way out and the various strands came together. People say I’m a conceptual artist, but I don’t know if every artist is conceptual. We all deal with ideas, but I like making things that have a sort of a physicality, even if it’s a small object.

I love process and I don’t know what things are going to look like, The Exploded Shed (1991), 30 Pieces of Silver (2015), Perpetual Cannon (2007), the last piece in the show, Island. I never knew what they would look like until I made them on the spot for an exhibition and I think when you have to make things under duress you kind of cut down all your decision making. I like being able to make work under pressure in a situation where it’s going to be seen at the end of it, because it allows your subconscious to surface and complete the work as it is.

With that in mind, when you look at a finished show and see it finally put together, does it feel different every time?

Yes, it does because when things are made, when they juxtapose with each other they can have all kinds of different meanings. That’s the beauty of including lots of small works. I like the way that they cross pollinate and become more than the sum of their parts. I suppose that’s what traditional sculpture was. A Henry Moore will stay like a Henry Moore, and it will always be the same, but somehow, I don’t feel like that about life. I feel life is very transient and very fearful, threatening. I want to be able to explore those feelings and let them come out, as if it’s a rite of passage. The poppy room, that piece, I think it’s got a short life on it because they’re just about to change the material which they make poppies to some nylon material, which I think would be horrible and not very good for the planet either.

Cornelia Parker, War Room (2015). Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London © Cornelia Parker.

I’m interested in your focus on aftermath, points of change, and what is left behind. You’re focusing on the things people usually forget, such as the work with shards of carvings from silver.

I remember going to a silversmith, not for the little shards of silver but noticing this guy sitting there in this dark basement, year in and year out, hand engraving into silver and gold objects, and there were these little tiny specks of silver everywhere. And I just said, “Oh, do you save those?” When he said no, because they’re not worth very much, I asked him if he could just put them in a jam jar for me and that’s what he started to do.

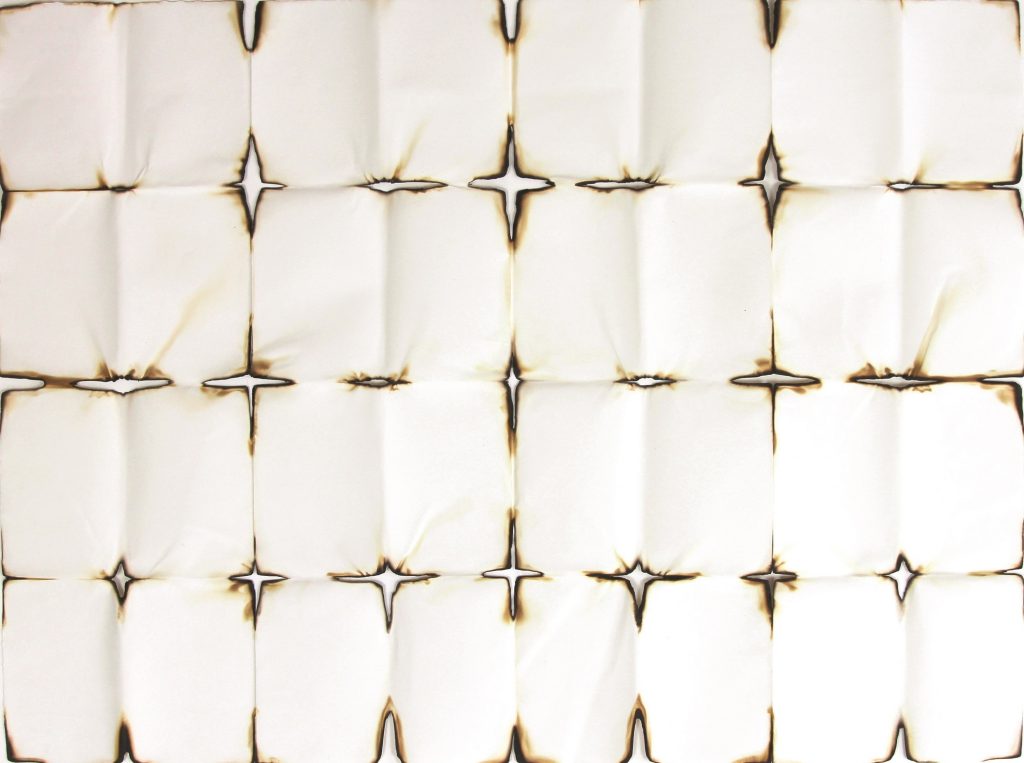

Cornelia Parker, Red Hot Poker Drawing (2013). Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London © Cornelia Parker.

There are strong political themes in your work which become more apparent over time. Was that something that built up over time?

Over time, because we live in much more concerning times now and the most concerning thing for me is climate change, that we’re sleepwalking into extinction. My 20-year-old daughter said to me: “Mum, do I get to have a future? Do I get to have kids?” This is a big major fuck-up by our generation, the people who are adults now that they’ve not managed to turn the ship around.

When accepted as the official election artist [a position chosen by a committee in the British House of Commons to document elections] I was immersed in politics. When they asked me, I thought well, why not? I’m reading newspapers all the time, I’m obsessed with the news. Perhaps I should just immerse myself in it, for good or for bad. I made three different films which are in the show: Thatcher’s Finger, Left, Right and Centre, and Election Abstract.

They told me after I accepted the job that I had to be nonpartisan, that I couldn’t show my politics basically and I thought that might be hard, but it was liberating. I was told to start social media, which I’d never done before, so I did Instagram. I made sure if this has been red to do something blue or yellow, and then left- and right-leaning cats….and all kinds of stuff. It may seem silly, but it was really good and every day I’d go into the newsagent and photograph the Daily Mirror with the Sun newspaper, the right- and left-wing newspapers in the headlines. It was somehow a relief to be immersed in it and then when I got to the House of Commons, which I’d filmed with a drone at night, and the next day, it just felt like a small, shabby little chamber… so I don’t know, the whole experience of it was quite immersive. Exhausting.

Cornelia Parker Left Right and Centre, (2017) (video still). Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London

© Cornelia Parker

Your success started at an exciting point in time in British art, and in politics as well. It was a time of change. What has it been like to see the art world evolve over the last 20 years or so?

It was quite amazing in 2000, when Tate Modern arrived on the scene and suddenly London became the center of the art world, and it was just a very vibrant place. Tate Modern opened with the Millennium Bridge linking it and St. Paul’s Cathedral which are opposite each other with the idea that art and culture were equivalent to religion almost. There was a lot of excitement about British art, and I am not so sure there’s that excitement now.

I was lucky because I went to art school when it was free and I went to art school for six years, Foundation, B.A. and M.A. I had a huge crack at the whip, we got money for materials, and if you couldn’t afford materials, you just used anything, which is what’s great about sculpture. You don’t have to have a big studio or lots of money to make art and so people are now making art in all kinds of ways, but 2000 was a pivotal point.

Lately it seems we can’t talk about art without talking about the market. What’s your take on the current state of the art market?

I don’t really think about it. My art doesn’t sell for millions. And, you know, it’s quite hard to sell at all, it’s quite big work. I never sell it to private collectors because if I do that they put it in an auction when they get bored of it.

I don’t ever want only oil people, arms dealers, or gas, or pharmaceutical people to own my work. I don’t worry too much if I’ve got enough money coming in to pay my bills, I’m fine.