People

Madagascan Artist Joël Andrianomearisoa Has Quietly Honed His Practice for Decades. Why Is He Suddenly Everywhere?

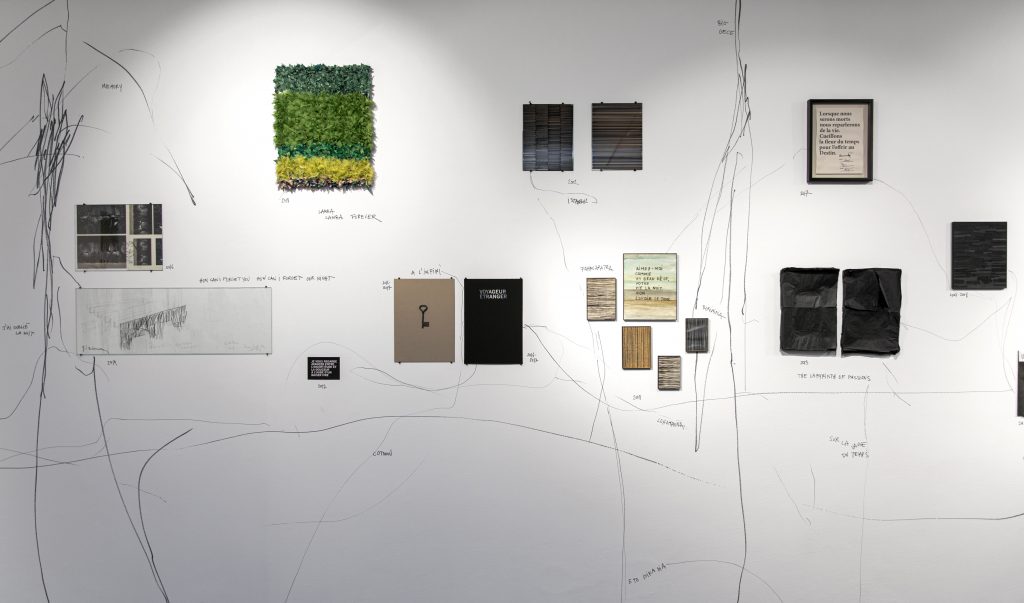

The artist's eclectic practice ranges from text art to textiles.

The artist's eclectic practice ranges from text art to textiles.

Julie Baumgardner

Two years ago, the Madagascar-born artist Joël Andrianomearisoa was invited to create a work for the opening of the Kunsthalle in Prague.

“The commission was to create a huge neon on the facade. I decided to make it in Malagasy—” his mother tongue—“so no one understands,” he said. “It was a kind of a big enigma on the facade of the museum.”

Was it a prank? A provocation? Not according to Andrianomearisoa. ”I’m convinced that the power of language is not just a text, not just an aesthetic element, but also the meaning. And sometimes it’s better not to understand.”

Andrianomearisoa, who lives and maintains studios in Antananravio, in Madagascar, Paris, and Aubusson, France, frequently moves between three languages. His English contains the melody of a polyglot and traces of places he carries with him. That he’s spread between so many physical geographies is reflected in Andrianomearisoa’s artistic identity—though Africa remains central to it.

“I am from Madagascar, when you see my name, there is no doubt about, you know my nationality,” he said, proudly.

Andrianomearisoa has had a prolific career over the course of three decades, though there’s a good chance you first heard of him in the past year. He was the unofficial star of the 1-54 fairs in Paris and Marrakech last year, and at the same time had solo shows at both his galleries, Primo Marella in Milan (who just bought his work to the Cape Town Art Fair) and Sabrina Amrani in Madrid (who brought it to Art Abu Dhabi, Art X Lagos, ArcoLisboa, Art Dusseldorf, and ArcoMadrid). The artist currently has solo exhibitions on view at the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town (until July 25), where he also just opened a gallery show with Church Projects (on view through April 28).

Joël Andrianomearisoa, shot of OUR LAND JUST LIKE A DREAM, MACAAL, Courtesy of the Artist and MACAAL, C. Ayoub El Bardii.

I met with Andrianomearisoa at the opening celebration for his exhibition “Our Land Just Like a Dream” at the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL), which had gathered some 1,000 guests.

Meriem Berrada, MACAAL’s artistic director, invited Andrianomearisoa with the prompt of “invading the museum,” as he put it. And invade he did—the exhibition, on view through July 23, occupies the entire museum, with each room transformed by in-situ installations, some immersive, others polyphonic, all revealing Andrianomearisoa’s adroit ability to evoke moods.

“Made in Marrakech, for Marrakech, and dedicated to Marrakech,” Andrianomearisoa said. He framed the show’s production concept around a collaboration—with Marrakech’s craftsman and artistic community, and with the museum’s collection. (He selected 15 pieces from the permanent collection to be woven throughout his own works.)

Everything from textiles, ceramics, metalwork, wickerwork, exhibition text, songs, even the exhibition’s own scent, involved an exchange between the artist and a maker in Marrakech. His assembled co-conspirators? Artists Amina Benbouchta, Amina Agueznay, Hindi Zahra, and Alexandre Gourçon, just to name a few.

“This collaboration actually is not just an invitation. [These artists] are part of the storytelling,” he said.

Joël Andrianomearisoa, “A few of my favorite things” from the show “Our Land Just Like a Dream” at MACAAL. Courtesy of the artist and MACAAL. C. Ayoub El Bardii.

His view of “the museum as a playground” guides Andrianomearisoa’s textures practice, which is expressed through textile works as much as metal sculptures, performance, photography, and commercial collaborations with brands like Dior, Diptyque, and Moleskine. (He doesn’t make products for these luxury houses but rather editioned artworks.)

Andrianomearisoa demures when it comes to defining his practice, other than agreeing it is research based and inquires into the materiality of the sentimental—the extreme world of emotions and the engagement of our five senses.

To encounter an Andrianomearisoa work in the wild (or in a gallery or museum) is to see fabrics composed and contorted into painting compositions or metal wrought into textual phrases from his own poetry. But his practice extends outside the white walls of any designated art space. He hosted a dinner-as-performance, for example, during last year’s 1-54 Art Fair in Paris.

He also makes “Sentimental Products,” epicure sundries to evoke the complexities of love, and whose sale, benefits the artist directly, is an incitement to the art market at large or “the game,” sliding himself into the position of autonomy. Andrianomearisoa leans towards certain mediums and aesthetic expressions, but largely he’s an artist motivated by concerns, moods, feelings, and has found materials and their converted forms of them that fit his reflections. It’s the ideas, the subversion, the critiques of structures and society that are Andrianomearisoa’s practice—the form needs to fit the idea, first, so he doesn’t fix himself to any particular mediums.

“The process depends on the project depends on the idea,” he said.

It might even be said that Andrianomearisoa is a master of context. What something is, where it’s sourced and then placed, who was involved—these are, in a way, materials for his practice. They’re also borne a very personal context for the artist—one that’s rooted in Africa. “Madagascar is for me—the craft is part actually of my practice, my production, and my inspiration also and it’s part of my soul,” he said. “But I’m not only an African contemporary artist.”

Andrianomearisoa said this emphatically. “I prefer to point to the idea of I’m not only. I’m part of the contemporary world wide point. I’m just an artist.”

And so, three years ago in his hometown of Antananarivo, Andrianomearisoa took “a real action on the continent,” and founded Hakanto Contemporary as a resource for artists that includes residencies (it receives funding from Fonds Yavarhoussen).

”It’s a platform. It’s definitely not a museum, it’s definitely not an art center, not a gallery. It’s a platform,” he explained, “to convince, not the government but more society that art has to be part of daily life.”

Joël Andrianomearisoa, installation view of “Our Land Just Like a Dream” at MACAAL. Courtesy of the artist and MACAAL.

So far, it has hosted more than 30,000 visitors to its six shows, which included works by more than 90 artists.

Hakanto currently has on view a comprehensive survey, “Esprit Revue Noire Une Collection Fondatrice,” reflecting on the pioneering African art journal that ran from 1990 to 2000, starting with a 1997 photograph of a Andrianomearisoa performance. “I prefer to talk about Africa with real action on the continent,” said the artist, “not just a blurry discussion appearing, like in Amsterdam on Saturday without any connection to the continent.”

“The cage, it’s dangerous,” Andrianomearisoa said of the typecasting artists from Africa often face. Hakanto has been a space to dispel preconceived notions and methods. “That’s my little action. Bring back this desire of being an artist to convince the community that it’s possible to be an artist,” he says, adding that Hakanto is hoping to engage its platform abroad with sights set on Asia.

“Most of the time, I’m not following the rules,” he said. “I’m not following the cliche, and I’m challenging the idea.” Then he added: “I’m challenging myself.”