People

Lin Tianmiao Speaks to artnet News About the Art of Endurance

Her work is more personal than political.

Her work is more personal than political.

Sam Gaskin

The most renowned work by Chinese artist Lin Tianmiao is The Proliferation of Thread Winding (1995), consisting of a bed with a mattress pierced by 20,000 large needles, each connected by white thread to a ball of cotton. A video embedded in the pillow shows her hands endlessly at work.

The lines of white cotton hint at a hidden psychological state, like a ghost’s motivating obsession revealed at the end of a horror movie.

Lin Tianmiao, Thread Winding (1995). Image courtesy of Lin Tianmiao Studio.

Winding cotton and silk around objects has been a mainstay of Lin’s practice ever since. “During the process I forget about everything,” she says. “It’s peaceful, and quiet. The head not controlling the hand. My thoughts go to deep issues.”

Lin has explained how from age four she was tasked with spooling cotton by her mother, a job she resented. When she had her own child, however, she reclaimed the act of winding cotton as a way of bridging two selves—daughter and mother.

There’s another experience, though she speaks of less often, that’s equally illuminating. Born in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, in 1961, Lin was a teenager during the Cultural Revolution. At that time, her father found her a job working as an apprentice making leather puppets.

“My father was trying to protect me from being sent to the countryside. I was going to be the last one to be sent, but because of the job I stayed in Shanxi.”

She would start at 4:30 a.m. each day, sharpening the puppet maker’s knives, which numbered over 100. “There was even a knife the size and shape of a grain of rice,” she says.

She was also required to study the puppets’ traditional face designs, headwear, and clothing, as well as the performances’ music and plots. Once she fully understood the way the puppets were meant to perform, and after balancing two bricks on the back of her hand to strengthen it against tremors, finally, after 10 years of training, she would be allowed to design the puppets herself and cut them from donkey hide.

Lin only apprenticed with the puppet maker for two years, earning a salary of just 18 RMB (about 9 USD at the time) per month, but she developed an appreciation for the total mastery of a craft. Lin’s work is marked by a deep sensitivity to materials that only comes through such prolonged engagement.

“Artists need to have different experiences, that’s what makes them different,” she says.

Unlike most successful young Chinese artists today, Lin didn’t transition immediately from art school graduate to full-time artist. During the early ’80s she studied art at Beijing’s Capital Normal University—not so much a fine art academy as a teacher’s training college—before leaving for New York with her husband, video artist Wang Gongxin, where she worked as a textile designer for almost eight years. During that time, she immersed herself in contemporary art, constantly attending shows and becoming friends with the likes of Xu Bing, Cai Guo-qiang, and Ai Weiwei. Yet it wasn’t until 1995, when she returned to China, that she began to create her own work.

Back in Beijing, Wang and Lin took up residence in a traditional courtyard house, which they converted into an open studio for making and showing work. Soon thereafter, Lin established herself as one of China’s first installation artists and one of the country’s few female contemporary artists.

Lin’s major exhibitions in recent years include the “Bound Unbound” retrospective at New York’s Asia Society (2012), “Est-ce permis?” at Galerie Lelong, Paris (2013), and “1.62M: Lin Tianmiao Solo Exhibition,” which opened on September 21 at the new 1,000 square meter How Art Museum in Wenzhou, China.

Curated by Chen Che, the new show includes pieces dating back to 2003, along with works that have never been seen before. It takes its name from the artist’s height, which is also the name of the first work viewers encounter in the exhibition: a plane of threads that runs the length of the entrance hall, forcing taller people to duck under it to access the other works.

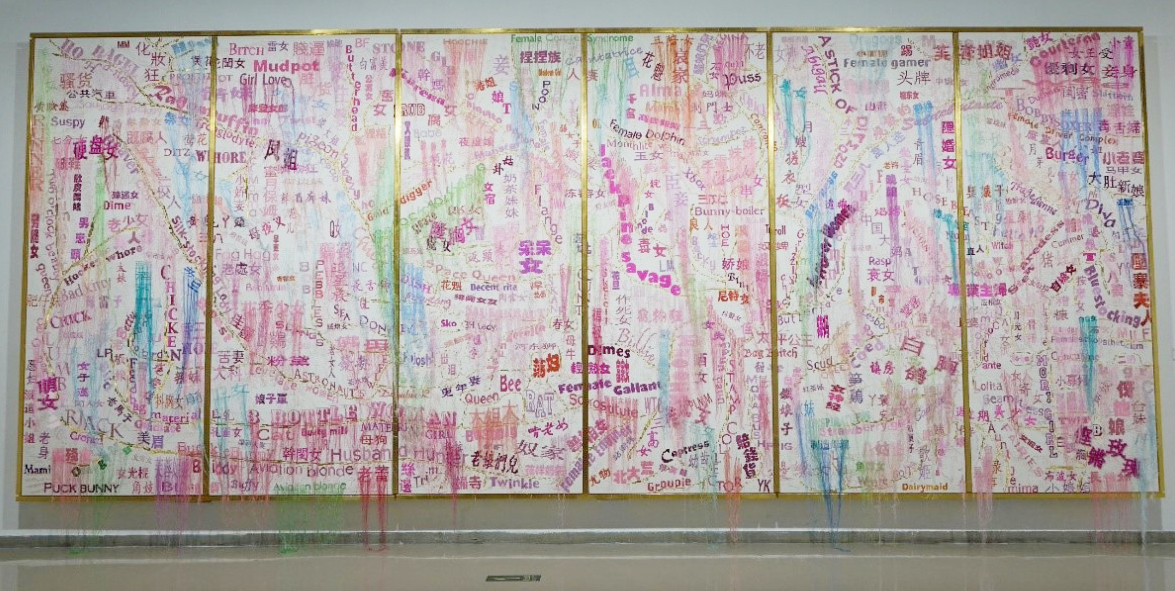

Of the new works, one called You! (2015) in English (and <妳!>, a rarely used feminine form of ‘you’ in Chinese), is derived from a series of work that Lin has developed over the past six years. The piece is a six-panel, eight-meter-wide wall of sewn-on terms, in English and Chinese, used to describe women. Words include: “captress,” “gold-digger,” and “ho-bagel”.

Lin Tianmiao, You! (2009–2015). Image courtesy of Lin Tianmiao Studio.

Lin has gathered over a thousand phrases, of which over a hundred have been in use for over a millennium; though she says it’s easier to find more recent terms as slang proliferates quickly online. Some—like “bitch” —are negative terms that have been adopted and repurposed by women, a tactic that Lin says “makes you not afraid of anything.”

It’s a work that many would understand as feminist, but Lin shies away from the term. She is tired of having to address “those issues,” she says, because her work is more personal than political, partly because of where she lives.

“Now it’s impossible to have feminism in China. We can still discuss it, but we’re not revolutionary enough or free enough to achieve change. It’s more important to input spirit into the work—fewer and fewer people are capable of doing that.”

It was partly in response to readings of her work as feminine and feminist—using materials such as cotton and silk, a high prevalence of pink in her work from 2004, techniques such as sewing—that Lin began incorporating more masculine elements, such as bones and tools, in her installations. But, as is often the case in Lin’s practice, the transition was also motivated by a personal experience: the death of her mother in 2011.

ALL the Same (2011) is a long line of resin bones tightly wound with a rainbow of brightly colored silks, while Loss and Gain (2014) grafts bones and tools together, denying the original functions of both to give them a new life. Here, tools evolve from metaphorical to literal extensions of our bodies.

Lin Tianmiao, ALL the Same (2011). Image courtesy of Lin Tianmiao Studio.

Lin Tianmiao, Loss and Gain (2014). Image courtesy of Lin Tianmiao Studio

The act of slowly, precisely binding items with thread seems like it could be either a kindness or an aggression, applying bandages or bonds. Lin says that “because the work takes a long time, I have all these feelings: smothering, protecting, and transforming.”

Another of the new works to show in Wenzhou is 1+1+1+1+1… (2015), a 2.9-meter-tall pastel-colored polyurea sculpture that shifts the tool-bone amalgamations into a more abstract form. Polyurea—often used to coat boats—is a favorite new material for Lin, and it too receives her full, indefatigable attention, including endless polishing and the application of color as softly as “the way we touch a baby.”

This slow, meticulous work is business as usual for Lin.

“Materials have to be discovered, explored, and pushed to their limits,” Lin says. “I’m not a conceptual artist. There’s more enjoyment for me in playing with materials.”

Lin Tianmiao, Toy 1# (2015). Image courtesy of Lin Tianmiao Studio.