Artists

‘Doubt Drives My Work’: Artist Nari Ward on How Uncertainty Can Lead to Discovery

The artist will be the subject of a retrospective exhibition at Milan's Pirelli HangarBicocca in early 2024.

The artist will be the subject of a retrospective exhibition at Milan's Pirelli HangarBicocca in early 2024.

Katie White

In a converted firehouse in Harlem, the artist Nari Ward experiments with shoestrings and scrap metal. The Jamaican-born, New York-based artist’s studio space is, in a way, a metaphor for his wide-ranging practice that uses a variety of materials—it is an oeuvre of repurposing, reimagining, and reawakening. He collects materials around his neighborhood—shopping carts, strollers, and old television sets—and works them into evocative artworks, often working at an ambitious scale, that ask challenging questions about our social and political realities. Thirty years into his career, Ward is currently making his London solo exhibition debut with “Balance Fountain” at Lehmann Maupin’s London location.

Ward, who is represented by Lehmann Maupin, is continuing this transformation process, creating art from humble objects. Currently, Ward is the subject of his London solo debut with “Balance Fountain” the gallery’s London space. in March of 2024, the artist will debut a retrospective exhibition at Milan’s famed Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, the former location of the Pirelli tire factory, which was converted into formidable exhibition galleries in 2012.

Curated by Roberta Tenconi with Lucia Aspesi, the exhibition will focus on Ward’s performance and collaborative projects, including video, sound, and performative installations. The show will include acclaimed set installations the artist made as part of a dance-theater trilogy by choreographer Ralph Lemon, first presented at the Walker Art Center in 1997. Combining new and historic works, the exhibition promises to be a nuanced look into Ward’s storied practice.

Recently, we caught up with Ward to find out what his studio practice has been like lately.

Nari Ward’s studio. Photograph by Axel Dupeaux. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London.

What made you choose your particular studio over others?

I found it in the ’90s when I was looking for a space to show my installation work for an exhibition I was working on for The Studio Museum called Amazing Grace. Initially I was looking for a church, but I couldn’t find any abandoned churches. Somebody told me about this old firehouse, and I was able to get in touch with the owner. They happened to be art collectors, and they were amicable to the proposition of me using the space.

Do you have studio assistants or other team members working with you? What do they do?

Yes, I almost always have studio assistants—especially when I know what it is that the work needs and can direct them. I have to figure it out myself first, and once I have a notion of what the expectation is for the work, I can bring somebody in to help me. I teach in the MFA program at Hunter College, and my studio assistants are almost always my students. It’s great to work with students that I already have a relationship with—one that’s been built up through their own work. I understand their skill sets, and they’re very engaged in what they’re doing in my studio because we have a shared history of trust to facilitate one another’s ideas.

Courtesy Nari Ward

How many hours do you typically spend in the studio and what time of day do you feel most productive?

It varies. I don’t always prioritize being in the physical space of the studio in my creative process—sometimes I get more out of walking down the street and around the neighborhood or seeing an exhibition. The studio is often a space of production more than one of inspiration.

So that being said, the amount of time I spend there really depends on what I’m working on and what my deadlines are. My time in the studio is, in many ways, driven by deadlines. It’s a place where I come to conclusions and a space that facilitates that necessity. At the same time, it’s a safe space where I can experiment.

When I am in the studio, I’m there from about 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., or sometimes longer if I need to be. I’m most productive in the mornings and evenings. It’s hardest to focus in the middle of the day—there’s just so much energy and intensity going on and in and out and around that it’s hard to be hunkered down in the studio.

Courtesy of Nari Ward.

What is the first thing you do when you walk into your studio?

I generally turn on the lights and walk back out. I don’t think about it as work in the sense that I have to clock in and out. If I don’t need to be there to complete or produce something specific, then I will go out and walk around the neighborhood or go to a place where I can watch people. I think one of my biggest hobbies is people-watching. I find inspiration from watching individuals and groups and thinking about what they’re engaged with—what they’re imagining, planning, and thinking about. My preoccupation beyond the studio is to be an observer of the rhythm and flow of people around the neighborhood.

What is a studio task on your agenda this week that you are most looking forward to?

This week I’m trying to finish a work—one of my large copper panel pieces from the Peace Walk series, where I sort of replicate and make reference to sidewalks and street memorials. It’s always exciting to be at the end of the process and to really understand and know where a work is going. I’m looking forward to hanging the finished piece and looking at it as a completed image.

What are you working on right now?

My process really depends on what I’m doing. I like to listen to music in the studio, but the type of music depends on the task at hand. If I am doing something very repetitive and monotonous or tedious, the music I choose would be much more rhythmic, like reggae or rap. If I am working on something more thoughtful and introspective, then I might choose classical or jazz music. I also enjoy silence.

Nari Ward, Peace Walk; ASSEMBLY (2022). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London.

What tool or art supply do you enjoy working with the most?

There are a couple of different tools that I enjoy working with. One is a brush spinner, which I used during my days as a house painter to clean brushes. Now I use this to twist various materials as well as spatter different kinds of liquid. I also like to use something called a chip lifter, which is generally used for computer repairs. It’s kind of like a small, flattened ice pick, and I use it to insert shoelaces into the wall when I’m working on my shoelace projects—it’s exactly the right size and angle for that.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get unstuck?

I never feel stuck. And here’s what I mean by that: doubt drives my work. So, “stuck” is not a word that resonates for me, because, to me, it implies that you know where it is you want a work to go and have been temporarily waylaid.

But I’m always excited when I’m not sure where I’m going or how my materials will respond. And in that way, everything is a discovery.

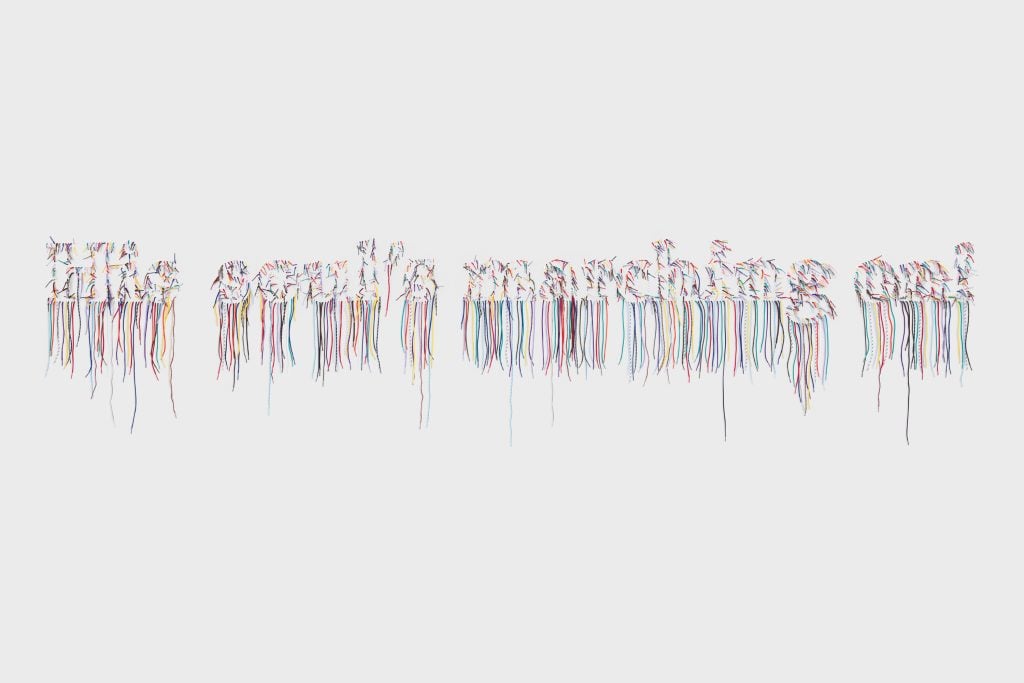

Nari Ward, His soul’s marching on! (2023). Courtesy of Lehmann Maupin.

Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

For the last few years, I’ve had an old project in my studio—a metal palmetto tree. It sits in the part of my studio that is open-air, and it has started to rust. Recently, mourning doves have been nesting in it. So there’s a beautifully preserved bird’s nest in this metal tree. And I always find that to be quite sad in some ways, but also very beautiful—a kind of testimony to nature’s strength and resilience. And maybe even, dare I say, a hopeful moment within a kind of desperation.

How does your studio environment influence the way you work?

I go through some phases where things get layered and chaotic. Things get messy, disorganized, and out of place. And I’m okay with that.

When a project is nearly complete, I don’t like messiness. I like it to be ordered and neat. So it kind of goes back and forth. I need to have things sane. And then when I get into the creative zone, I don’t mind things falling apart around me.

Describe the space in three adjectives.

Salvation, doubtful, and fortunate.

Courtesy of Nari Ward.

What’s the last thing you do before you leave the studio at the end of the day?

After I turn the studio lights off, I go upstairs, where I live. I really believe there is both a benefit and a curse that comes with living and working in the same space. And as much as I try to delineate between the studio and the home, there is no clear boundary. Often, If I can’t sleep or something inspires me, I just go back downstairs. I’m always here. I feel like the studio is ongoing—just waiting for me.

What do you like to do right after that?

When I am not with my family, I love to walk around hardware stores, especially right after leaving the studio. Usually, I’m there to get some material to set the studio up for the next day.

Hardware stores supply materials that facilitate repair. So I always feel like it’s a very hopeful environment. Anything can be made or remade, and almost anything can be fixed. I like the idea that—with the right knowledge—there are endless possibilities. And this is not a Home Depot or hardware commercial… It’s just a testament to the intensity of my need to both make things and make sense of things.

More Trending Stories:

Art Critic Jerry Saltz Gets Into an Online Skirmish With A.I. Superstar Refik Anadol

The Old Masters of Comedy: See the Hidden Jokes in 5 Dutch Artworks

A Royal Portrait by Diego Velázquez Heads to Auction for the First Time in Half a Century

How Do You Make $191,000 From a $4 Painting? You Don’t

In Her L.A. Debut, South Korean Artist Guimi You Taps Into the Sublimity of Everyday Life

Two Rare Paintings by Sienese Master Pietro Lorenzetti Come to Light After a Century in Obscurity