Art World

An Artist Completely Reconstructed the Body of a 7,000-Year-Old Female Shaman. Here’s How He Did It—and Why

Reconstruction artist Oscar Nillson used cutting-edge techniques to resurrect the ancient figure.

Reconstruction artist Oscar Nillson used cutting-edge techniques to resurrect the ancient figure.

Maxwell Williams

Oscar Nilsson is a world-renowned reconstruction artist, taking the remains of prehistoric humans and bringing them back to life using a complex system of anatomical analysis, 3D printing, and occasional DNA analysis. But what’s equally vital to his job is a sense of context.

Archaeologists found the remains of a 7,000-year-old in the early-1980s. Recently, Nilsson was tapped to resurrect her. First, the reconstruction artist carefully considered the items that had been buried with “the Woman from Burial XXII,” as she was known to the team that excavated her grave at the Late-Mesolithic site in Skateholm, Sweden, one of the oldest known cemeteries in the world. Nilsson’s reconstruction of the woman, known informally by Nilsson as “the Shaman,” was revealed as part of “Eye to Eye,” a permanent exhibition featuring several Skateholm burials, on November 17th at the Trelleborgs Museum on the southern tip of Sweden.

How Burial XXII was found by Lars Larsson’s excavation team in the 1980s.

A bit of detective work was required. “How people are buried tells us so much of their status and role in life, socially as well as economically,” Nilsson told Artnet News in an email interview. “Following this thesis, our woman from grave XXII must have been a special one. She was buried in a sitting position with her legs crossed, on the horns of a red deer…. All in all, she must have evoked respect in her time, in her social context. A respect that can still be felt and experienced, looking at the excavation photos and, hopefully, my reconstruction.”

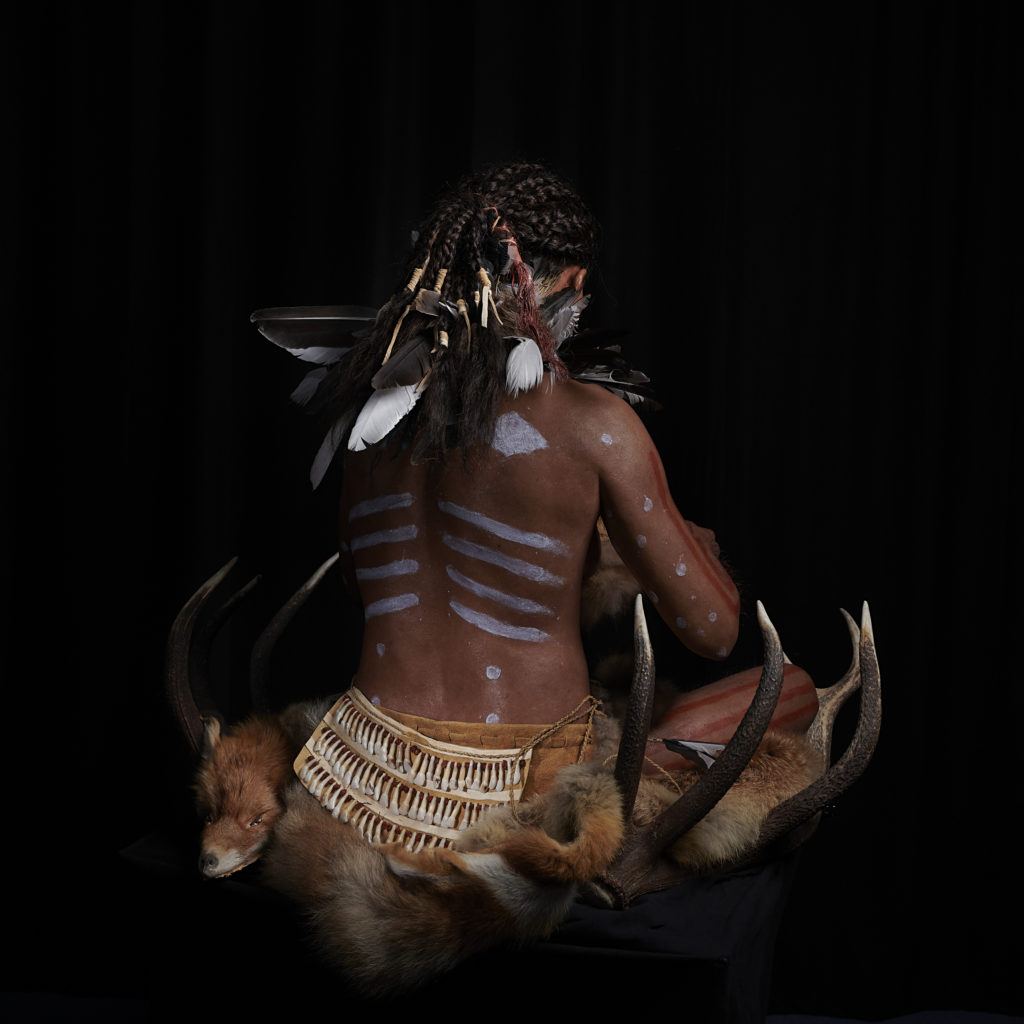

Nilsson’s reconstruction shows a dark-skinned, blue-eyed woman sitting cross-legged, much like a shaman would. An animal tooth belt is fashioned around her waist, as she was found in her burial site with 130 animal bones. And a “very special… slate necklace [unique to] Northern Europe” was found around her neck, says Nilsson.

There were more than 80 graves found in Skateholm, a society of hunter-gatherers. Archaeologists date the sites back to approximately 5,500 to 4,600 B.C.

“Her DNA is not that well preserved and the colors of hair, eyes, and skin can not be determined,” he says, admitting that the Shaman’s features were an estimation. “But the dark skin and blue eyes are the best-qualified guesses we can make today, knowing these colors and this combination seems to have been the most common one among the hunter-gatherers in this time, in this region, based upon well-preserved DNA from other burials.”

Nilsson is uniquely qualified to make these reconstructions. Having studied both art and archaeology in the early 1990s, Nilsson founded his studio, O.D. Nilsson, in 1996. He later studied in Manchester, England, learning a widely accepted process of forensic reconstruction called the “Manchester method,” where faces are reconstructed one layer at a time. Though he is not the world’s only facial reconstruction artist, he has worked with some of the most prestigious institutions in the world, including the Stonehenge Visitors Centre, the Vasa Museum in Stockholm, and the University of Athens in Greece.

Since he’s being commissioned by history museums that trade on accuracy and veracity, the process is as complex as one might imagine.

“One must have great insights into the human facial anatomy as well as specialized skills in sculpting, and a lot of passion for history, I guess,” he says.

Other Skateholm sites were notable in that some included burials of people with dogs, and there were even sites with just dogs, who were buried with grave offerings.

He starts by examining the tissue depth of the face, and rebuilding facial muscles, before using tried-and-true methods for the reconstruction of the nose, the eyes, and the mouth. (While it wasn’t the case with the Shaman, he often relies on well-preserved DNA to inform eye, skin, and hair color.) He then makes a 3D printed copy of the original skull using plasticine clay. He casts the head in skin pigmented silicone, and then adds real human hair, “strand-by-strand,” he says.

“The body is not a proper reconstruction; it is a lifecasting from a living person with the same measurements, physics, and stamina as what can be determined from the skeleton,” he says. “[And then the reconstructed body is] also cast in silicone, of course.”

But what makes Nilsson’s Shaman, and his other reconstructions, so lifelike is his attention to detail and a desire to truly bring the subject to life.

“I guess what makes my reconstructions special is the sense of presence in the faces, that I work so hard to achieve,” Nilsson says. “It is my belief that the more realistic a reconstruction can be made, the more emotional impact it creates. And it is my hope that by doing so, my reconstructions can generate a greater interest for history and the people of the past.”