Art World

There’s a Thriving Underground Barter Network Among Artists. Doug Aitken, Dread Scott, and 12 Others Tell Us About Their Most Memorable Trades

Artists reveal the touching stories behind their most prized swaps.

![John Baldessari, Frames and Ribbon [detail] (1988). © John Baldessari. John Baldessari, Frames and Ribbon [detail] (1988). © John Baldessari.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2019/04/top-half-john.jpg)

Artists reveal the touching stories behind their most prized swaps.

![John Baldessari, Frames and Ribbon [detail] (1988). © John Baldessari. John Baldessari, Frames and Ribbon [detail] (1988). © John Baldessari.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2019/04/top-half-john.jpg)

Artnet News

Much of the conversation around art (too much, some might say) revolves around astronomical prices paid at auction. But there’s an entire shadow economy operating just beneath the surface of the art world that involves no exchange of money at all.

Behind studio doors, outside the sphere of art dealers and collectors, artists are engaging in old-fashioned barter. By trading with peers and admirers, they can assemble holdings that rival any number of traditional big-money art collections. “If you do it enough times, it’s a retirement plan,” says artist Jared Deery.

Like any industry custom, it comes with its own rules: Offer work of equivalent scale or significance. It’s OK to follow up. And be generous.

“I’ve been in situations where artists maybe don’t want to trade for their best work because they’re sitting on it in hopes of one day showing it or selling it,” says artist JJ Manford. “You have to get over that; if you get a gem, give a gem.”

Once the negotiations are done, trades can offer endless amounts of inspiration. We asked 14 artists to recall their most memorable swap. Here are their stories.

Walter De Maria, High Energy Bar No.81 (1966), traded to Judith Bernstein.

Walter De Maria was a very good friend of mine and a former boyfriend. I met him at a Bill Copley opening in 1971. We were the only people there! We both showed up on the wrong day. We were close for more than 30 years, from 1971 to 2013, when he died.

Judith Bernstein, Horizontal (1973), traded to Walter De Maria.

He gave me High Energy Bar No.81 (1966) in exchange for lending him some money because he couldn’t get to an ATM when he was scouting out the location for The Lightning Field (1977). I gave him a drawing when he lent me some money for my trip to Europe with the Guerrilla Girls. It was a prototype for my seminal piece, Horizontal (1973). I was thrilled to get such an extraordinary piece from such an extraordinary artist, and he was too.

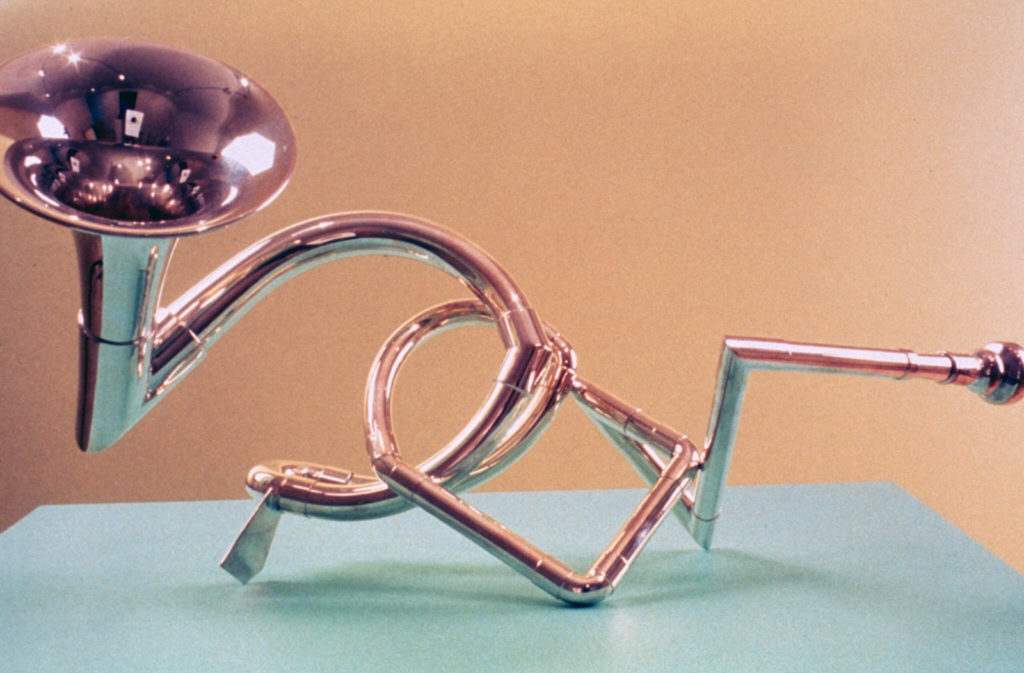

Carol Szymanski’s phonemophone horn sculpture (1994), given to Joan Jonas.

My most memorable trade was with Joan Jonas in the mid-1990s. My husband Barry and I would go to Joan’s studio in SoHo for parties where she often did impromptu performances or would break out into dance with her props around her. These were very special moments, to say the least. I had given Joan one of my phonemophone horn sculptures, a brass trumpet. But we never got around to completing the trade.

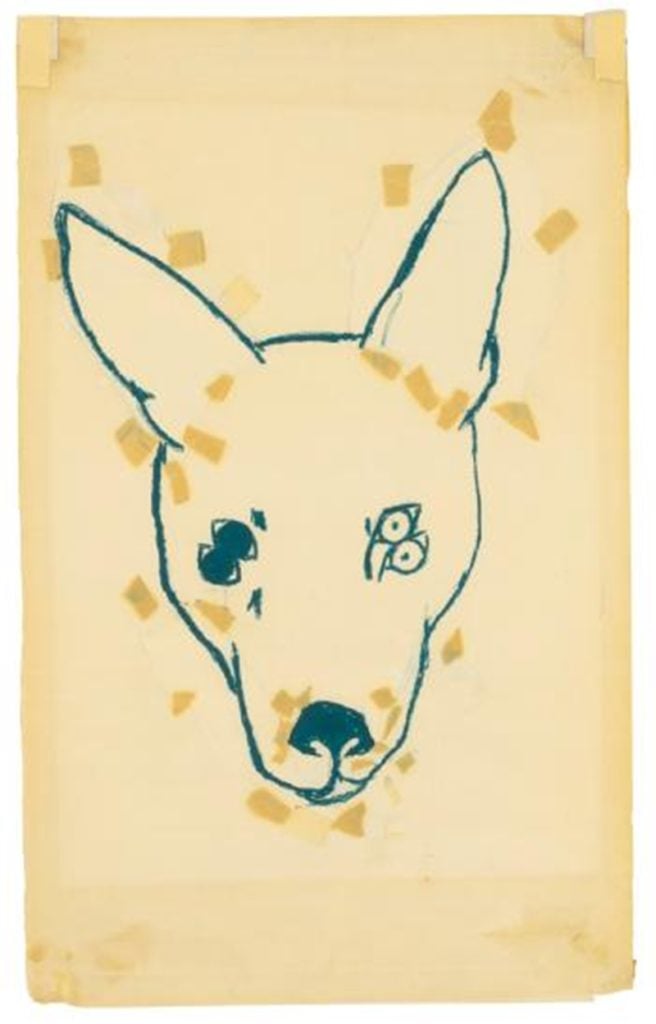

One of Joan Jonas’s drawings from the “Organic Honey Vertical Roll” series, similar to the one traded to Carol.

At one party, I reminded Joan that we had traded. So at that moment, she broke into a performance and suddenly yanked this big framed drawing of a four-eyed dog—a most incredible drawing from the period of her “Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll” series (1972)—from the central spot in her loft and handed it to me in front of all the guests. I will never forget that moment and this drawing is my most beloved artwork.

Still from Eva and Franco Mattes, Head Tree. Courtesy of the artists.

David gave us a unique, blown-glass tear made from blue found seaglass. We gave him a video called Head Tree, inspired by instructions David wrote years ago for one of his works.

A glass tear drop by David Horvitz, given to Eva and Franco Mattes.

We just love David’s practice—everything he does is at the same time conceptually clean and very poetic. It’s very rare to find both characteristics in the same artist.

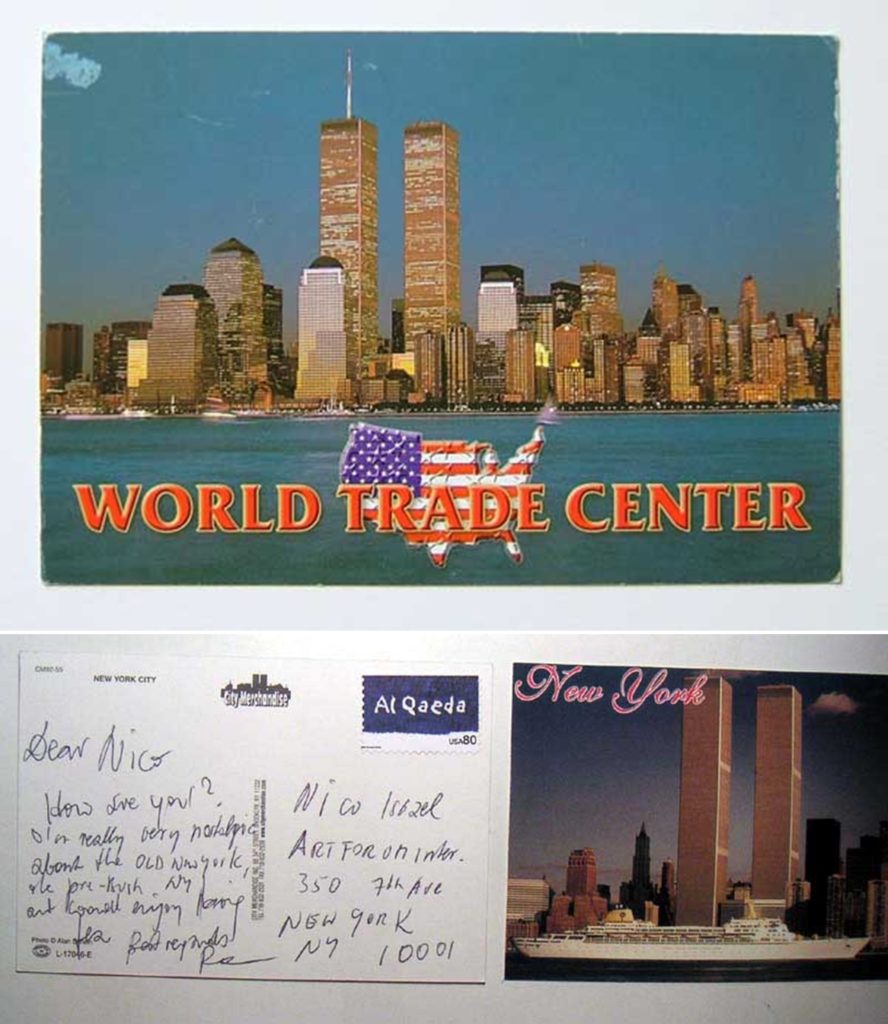

When I met Carolee Schneemann, I asked her whether we could trade and I sent her a series of about 10 or 12 postcards from the World Trade Center with my fake stamps, a form of mail art. She sent me back a drawing.

Examples of World Trade Center postcards.

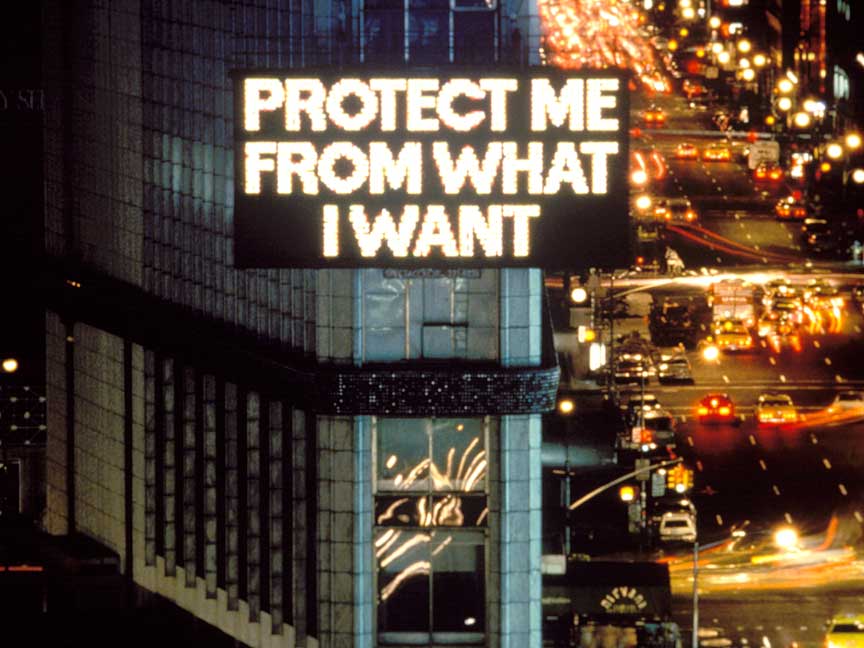

I also sent a set to Jenny Holzer in around 2003 or 2004, who gave me a complete set of signed posters she had put in the street from the ‘80s in exchange. I was impressed by her generosity. But the best part was that Jenny told me she was called by the FBI because they wanted to know who “this person sending images of New York Landmarks with weird messages and stamps through the mail” was.

An example of Holzer’s “Survival” series (ca. 1983-5). © 2007 Jenny Holzer, member Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Many years ago, in the mid-1980s, my partner at the time, Haim Steinbach, and I sold our work to Best Products. The set-up was that instead of money, we would get the value of the artwork in goods from their catalogue.

We were friends with Sherrie Levine, who really wanted a washing machine and dryer—so we made a side deal with her. She got the appliances and Haim and I each got a watercolor in exchange—a Schiele and a Mondrian, respectively.

I got this call from Franz, who was in Europe at the time. He said, “Doug, I’m standing in front of this kinetic wall [Wilderness, 2006] that you made and I really love it. I’d love to know if you’d trade it.” Franz was a very good friend, so I said, “Of course, take it, it’s yours. It would be an honor for you to have it.” And he did. And he said, “I’ll make you something in exchange.”

Doug Aitken’s WILDERNESS (2006). Courtesy of the artist.

I thought nothing of it. Some time passed, and about a year later I get these calls from my studio saying, “You’ve got to get over here quick, there are these huge boxes and we don’t know what they are.” We crow-barred out the boxes, and there was this large, freestanding sculpture by Franz, unlike anything of his I’d ever seen. Usually his works are pastel, this one was red and orange, very extreme. It was splattered and expressionist.

Franz West, Untitled (undated). Photo by Ye Rin Mok. Courtesy of Doug Aitken.

Staring at the work on the sidewalk, I called up Franz and said, “First, thank you for sending me this piece but I want to know, what is it?” He said, “You know Doug, every time I come to Los Angeles, we have lunch, and I’ve noticed there are several words that you say in a conversation. You always say the word ‘revolution’ and ‘revolutionary,’ and when we last, met you also said ‘meteorite.’ So I have made you a Revolutionary Meteorite.”

It is a biomorphic shape that looks almost like a riot has happened on top of it. I love it because we were playing off each other. It was about sharing ideas and conversations through art. It is still in my house. It has its own room. Sometimes I go an sit with it because Franz isn’t around anymore.

Brian put together a drawing show in 2013 called “Draw Gym” at Know More Games in Brooklyn. He invited more than 70 artists to contribute drawings and covered the floor of the space with hundreds more found drawings, possibly from thrift stores or maybe art-school trash cans.

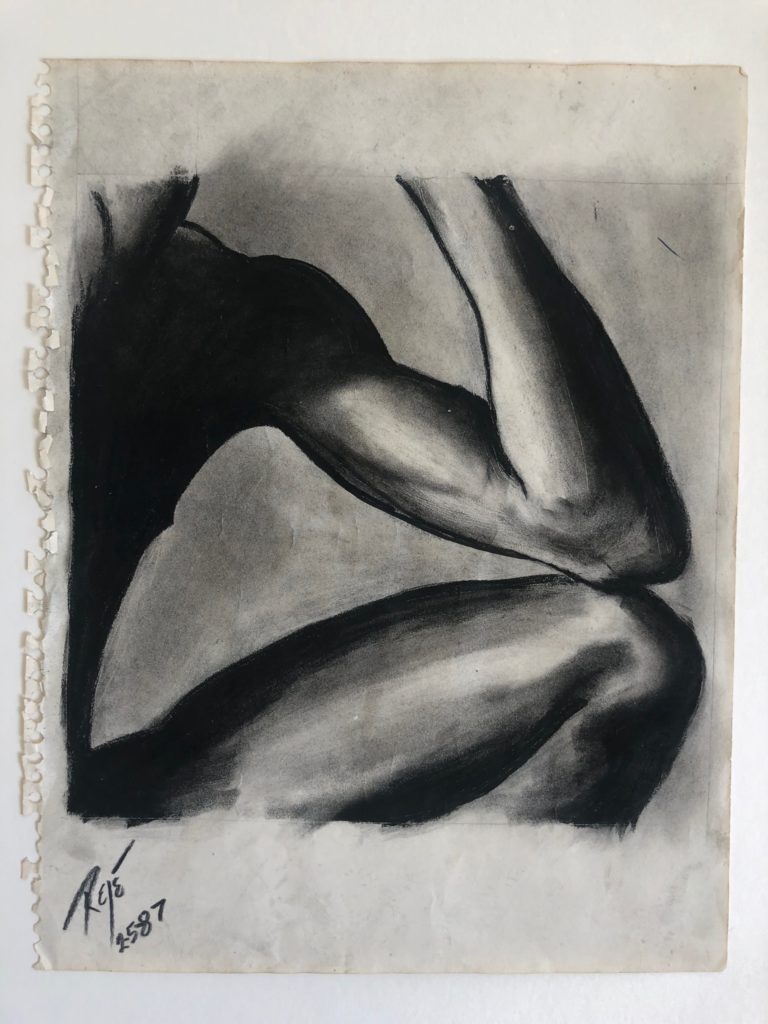

The drawing by “Reje” that Gina Beavers traded for.

They were free to take, and I picked up a charcoal drawing by a[n artist called only] “Reje” (signed with a flourish) dated 2-5-87. The drawing is of the left side of a crouching nude man, his muscle-y arm and thigh emerging from the dark shadows of his torso. I framed it and kept it around and it influenced paintings I began to make of bodybuilders. I never got my drawings back from the show (totally my fault), but I always considered it a fair trade because I love my drawing.

Rashid is literally one of my best friends; I love that dude. He has seen my work evolve and at the same time I’ve seen his evolve and we really admire each other. There was a point where we really wanted to make a trade.

Rashid Johnson’s Rumble (2011) on view at Hauser & Wirth, similar to that traded to Angel Otero.

Rashid came to visit me and saw this specific pink and yellow abstract skin painting. I remember him taking it. And then we were hanging out maybe a year later and I was like, “Okay, dude, I want my Rashid Johnson.” [Laughs] It was taking way too long. And he put something aside for me and said, “I don’t want to see it [again]. Because if I see it, I might change my mind.” He put my name on the back of it, and then I had to rent a truck and have it picked up ASAP. [Laughs] I’m pretty sure the work doesn’t have a title, but it’s from his wood floor series with black wax.

I was quite close to Martin Kippenberger. The first piece he got of mine was a unique work that he saw in my studio. After this he collected two more small sculptural editions that I produced with Gisela Capitain, where both of us showed.

Jon Kessler, Girasole (1987). Courtesy of the artist.

I wish I could say that I have three Kippenbergers in my collection, but alas I have none! Every time I’d go to Martin’s studio we would end up so drunk that we never got around to picking anything out.

Gisela, in her graciousness, tried to complete the trade and offered me works of Martin’s from her archives. But stupidly I was being picky and kept waiting for just the right piece to come along. After a while Martin moved to Austria, we lost touch with each other, and then sadly he died at 44 years old.

Whenever I’m in Berlin I would be reminded of our lopsided trade when I’d see my works hanging in the Paris Bar where Martin showed off his collection.

Jared Deery ended up giving me a painting that I co-curated (with Ashley Garrett) into a show at Underdonk gallery, in Brooklyn. The show was called “Paul Klee” and the works in the show were loosely inspired by the Swiss-born German artist.

The painting is called Awake in The Night, and it happens to be my favorite work from that show. Recently, the artwork showed up on Amazon, as it seems that a group of entrepreneurial techno-crooks stole the image and were trying to sell it as a shower curtain, bath towel, tote bag, and a few other things. Jared asked me if I had done it!

Jared Deery, Awake in the Night. Photo courtesy of Jared Deery.

Oskar Dawicki’s Speech is Silver. A sculpture inspired by tales of a medieval torture method which entailed pouring molten metal down the throat of a perjurer. It consists of a silver cast of an anatomically correct fully rendered negative of the mouth cavity and a fragment of the esophagus—the sculptural imagination of such a radical punishment. The process of creating the sculpture—as the artist’s preferred method of suicide—is one of the themes and climaxes within the award-winning film Performer (2015), directed by Lukasz Ronduda and Maciej Sobieszczański, on Dawicki’s oeuvre.

Oskar Dawicki, Speech is Silver (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

While trades with artists can be blissfully free of any monetary transaction, it’s not always the case. It’s important not to brush aside the potential financial implications of a trade for a given artist: from structural inequalities to differences in market value to other considerations. On more than one occasion, we’ve traded a work of lesser (market) value and supplemented the difference with money.

We have been friends for a long time. We traded prints, and I think I gave him three for two. It was one of his first reflective series. It’s a black man tied to a whipping post with a crowd of onlookers. It’s hanging in my living room.

When you trade art, by and large the question of value falls out of the equation. It’s more, “I like this.” “I like this.” If I’m trading with a younger artist, I’m trying to give him stuff that takes a similar amount of labor. The big thing for trading is I wish I had started earlier. There are some artists who I was friends with and now they are a really big deal. Now I can’t really approach them and say, “Man, can we trade?”

We each made an original work for each other on an 11 inch-by-11 inch hankie. This is part of a larger project by Claudia and her collaborator Cecilia Mandrile called The World Is a Handkerchief, in which each of them printed a work in an edition of 25 on a handkerchief and traded it to 25 members of their “creative and created family” willing to do the same.

Mano di Claudia Panuelo, traded to Betty Tompkins. Courtesy of the artist.

Claudia and I traded work when we first met in 1975. Since then, she has done very large projects like Women of the World, which has a piece from each country in the world made by a woman. So it is a lot of fun to do it again.

My most memorable trade is a swap with New Zealand (and Los Angeles-based) artist Fiona Conner in about 2013, in which she raised (by 500mm) and replicated my bedroom floor (in a rented home) as a surprise gift for my wife’s birthday. We lived on the platform-work for about a year before sadly having to move.

Remember to document temporal architectural interventions when renting.