Art & Tech

‘An Echo Chamber of This World’s Order’: Stephanie Dinkins, Linda Dounia, and Marianna Simnett Confront A.I’s Ethical Tangle

The artists explore the ethical gaps and questions that A.I. poses.

The artists explore the ethical gaps and questions that A.I. poses.

Min Chen

This is part of a series on how artists are approaching the age of A.I. Read part one here.

Being a tool for creativity has pretty much paved the way for A.I. to enter the artist’s toolkit—but the technology has also touched off essential debates (and lawsuits) over its ethical gaps. That popular datasets have been trained without consent on a corpus of copyrighted material is but one thing; the tool has also proven to harbor in-built biases that misrepresent and often omit marginalized communities.

And what does it mean for human labor and authorship when machines are part of the creative process? Will A.I. threaten artists’ livelihoods?

In the second part of our series on creative approaches to A.I., artists Stephanie Dinkins, Marianna Simnett, and Linda Dounia tackle the artistic and ethical pitfalls that come with the tool. Just like anyone else, they don’t have all the answers as the technology continues to evolve, but their tangling with the question reveals how the tool is reshaping all aspects of creative work.

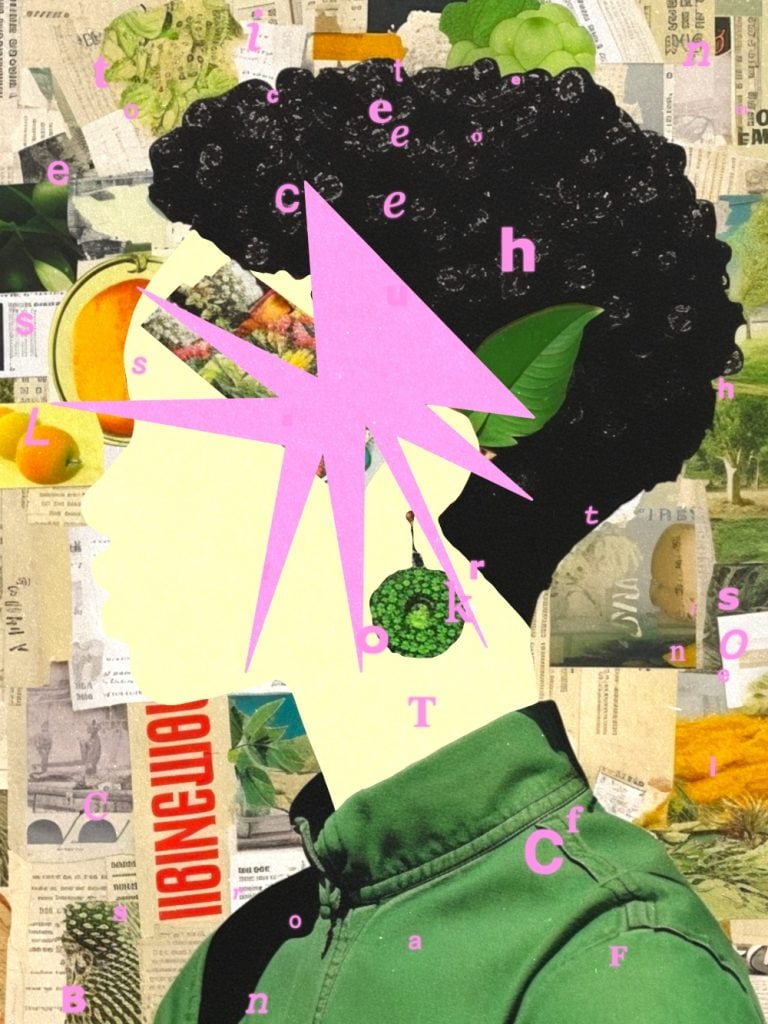

Linda Dounia, Chez Jo. Courtesy of Feral File.

That A.I. bears the biases and prejudices of its makers is not a revelation for the Senegal-born artist. This fact has not stopped—but spurred—Dounia to more actively engage with A.I. She compiled datasets to train her own generative adversarial networks long before the explosion of generative A.I. tools, and, more recently, curated the incisive “In/Visible” exhibition for the digital platform Feral File. Addressing and correcting a tool and space that’s long been exclusionary is work that she views as urgent and political.

What does A.I. mean to you as an artist?

I don’t believe technology exists in an apolitical, post-racial, and post-colonial vacuum. Though autonomous in its workings, A.I. is constructed by humans. The data used to train it is gathered by humans. Humans are political entities. It should therefore be no surprise that A.I. reflects the same biases and exclusionary practices that define our time.

If anyone is doubtful that A.I. is biased, I encourage them to ask ChatGPT themselves. Here is what it told me when I asked it about its ability to represent Black people: “While my training data includes information about Black cultures, I recognize that my understanding is limited by the quality, diversity, and biases present in the data.”

I buy into the promises of A.I. while understanding that it has the tendency to be an echo chamber of this world’s order. This makes my relationship with it complicated but also makes my participation critical.

What considerations do you take into account when using A.I. as a creative tool, particularly with the Black misrepresentation in these models?

I started incorporating A.I. in my practice because I was afraid that if I didn’t, I and everything I represented would be erased from the digital memory of the world. Responding to the biases of A.I. in representing Black cultures felt urgent to me. Then I met other artists who were also brute-forcing A.I. tools to tell their stories. They achieved this with persistence and stubbornness, endlessly re-prompting, correcting distortions, and editing out stereotypes. I was convinced that what we all did was a form of resistance.

How has your work with A.I. changed or impacted your practice?

Having experimented with A.I. in more ways than I could possibly fathom, I feel a deeper sense of progression and connection with my craft. It scratches my itch for divergence and scale, and it’s a bottomless pit of exploration. My chief issue with it, namely its bias towards Eurocentrism, is not one that I believe can’t be overcome. My hope for the future, through my work and that of other Black artists exploring it today, is that it will grow to reflect the vastness, richness, and diversity of the world.

Stephanie Dinkins, Not the Only One, V2 Avatar, Becoming (2020). Photo: Stephanie Dinkins.

For Dinkins, who won the first LG Guggenheim Award in May, A.I. poses disruptions to social realities, but also serves as a useful tool to interrogate its impact. She’s built a “social robot” and a large language model that centers Black voices, among other efforts to probe just how the intersection of technology and humanity could reshape—and challenge—our understanding of labor, storytelling, authorship, and creativity.

How has A.I. challenged you as an artist?

I’ve been using A.I. as a tool and a partner, and it challenges me to see what it’s doing and to be aware of how it’s working. Through touching it and playing with it and getting my hands dirty, I understand more about the way that it is working, which then gives me more liberty in the ways that I use it.

But for artists, it challenges us to be flexible and fluid in the way that we do things. It challenges us to nurture our own creativity through ways that extend beyond what the machine might do or be augmented by what the machine might do. It’s going to challenge us a lot to think about how we make what we make—and our ability to make money. That’s a big question: where is the exchange value? We’re going to have to think hard about what’s important, and then the value of what we do by hand or by voice or by whatever that can be mimicked by a machine. How do we value that in terms of when it’s human-made versus when it’s machine-made?

How do you see the emergence of A.I. generators reshaping art-making?

My work with A.I. has been about experimenting and testing what the system is doing and what seems to be possible. But now, almost anyone can have an idea and then have that work—and they’re using the work of others or museum collections as the basis for that. What does that mean for the way people get paid? Or the way that copyright works? What then does it mean that artists have to shift to work differently? How does A.I. become a collaborator, versus something that’s taking over?

That’s just the tip of an iceberg. How are we going to really deal with it so that things are possible, but people still have the possibility of getting paid for their labor with all the changes that tech has brought. If we were listening to the Uber drivers a long time ago, we would have heard that while [tech companies] are giving us a certain kind of freedom, they are also limiting our income. We need to be prepared to rethink, to a large extent, our systems.

Marianna Simnett, GORGON (2023). Commissioned by LAS Art Foundation. Courtesy the artist, LAS Art Foundation, and Société, Berlin.

In her new work, GORGON, Simnett has embodied her titular monster with all the fears surrounding A.I. today. The flute opera, which recently premiered in Berlin, has been built with help from visual and audio datasets, but more so in its narrative, captures the push-pull between humans (in the main character Greta) and technology (the flutes). A.I. and artists are bound for a joint future, said the Berlin-based artist, but not before “a constant process of intricate negotiation.”

In creating GORGON, how has A.I. challenged you as an artist?

The biggest challenge was, unsurprisingly, learning to lose control. It was really interesting how, with just the slightest prompts, it would make me look like Barbie or an Orc from Lord of the Rings. I guess the enormous prevalence of images posted online was creating a subset of heavily biased images that were feeding into my own data. Trying to synthesize my painstakingly crafted footage and not let the machine totally destroy it with goblin and comic book characters was a battle.

A.I. has also challenged my understanding of chronology and time. I am less and less interested in linear storytelling, and more into the interdependence of knowledge systems across different times, species, and borders.

What ethical pitfalls do you see in the use of A.I.?

I think A.I. is definitely altering the criteria of what qualifies as good art. If your primary concern as an artist is to render perfect, realistic images, then maybe it’s time to jump ship. But artists historically have always found ways to assert themselves against threats of obsolescence, and A.I. is no exception. People are always going to be interested in what artists do, not because of what tools they use, but how they use them. This phenomenon is so inexplicably charged, fundamentally human, and I think sublime.

Artists rights will undoubtedly be misrepresented and their work stolen for nefarious means. Laws around intellectual property cannot keep up with the speed of change right now. But it’s also up to artists to get on top of this rapid acceleration and find their own slipstreams against the tide of capital.

How do you see the relationship between A.I. and human artists evolving into the future?

I see A.I. and humans being friends in the future, maybe even more than friends. Many of us are already using A.I. in our daily lives without even realizing it and it seems clear our future relationship is completely entwined.

For artists, I see the individual “genius” losing status, moving towards a symbiotic, cyber state with other cells, structures, roots, networks and organisms. We will all have to accept our hybridity. That might not be such a bad thing.

More Trending Stories:

Art Dealers Christina and Emmanuel Di Donna on Their Special Holiday Rituals

Stefanie Heinze Paints Richly Ambiguous Worlds. Collectors Are Obsessed

Inspector Schachter Uncovers Allegations Regarding the Latest Art World Scandal—And It’s a Doozy

Archaeologists Call Foul on the Purported Discovery of a 27,000-Year-Old Pyramid

The Sprawling Legal Dispute Between Yves Bouvier and Dmitry Rybolovlev Is Finally Over