People

‘The Kids Will Be Fine,’ Larry Clark Says Ahead of His Upcoming LA Retrospective

The show will include Clark's rarely seen paintings.

The show will include Clark's rarely seen paintings.

Henri Neuendorf

Known for his shockingly frank and provocative depictions of youth culture, the photographer and filmmaker Larry Clark has divided opinion for over five decades.

Clark rose to prominence in the early 1970s for capturing the casual drug use, sexual exploits, and violence propagated by himself and his peer group in his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The resulting publication, Tulsa, which documented their lives between 1963 and 1971, earned him fame and notoriety by disrupting the wholesome stereotype propagated by suburban Americans.

UTA Artist Space, the Los Angeles-based talent agency’s 4,500 square foot exhibition space. Photo: courtesy UTA.

His subsequent photography throughout the 1980s and 1990s explored the sexualization and demonization of youth culture by mainstream society and the mass media, culminating in his legendary cinematic debut, Kids (1995).

Since that time, he has made a host of award-winning movies, including Another Day in Paradise (1998), WASSUP ROCKERS (2005), and Marfa Girl (2012), which won the Marcus Aurelius Award for Best Film at the 2012 Rome Film Festival.

On September 17, Clark will inaugurate the talent agency UTA’s new 4,500-square-foot art space in downtown Los Angeles, in a show that will survey his films, photographs, paintings, and collage. Ahead of the exhibition, artnet News sat down with the artist to speak about the differences between film and photography, the value of “shock” in the digital media age, and Clark’s own fascination with youth culture.

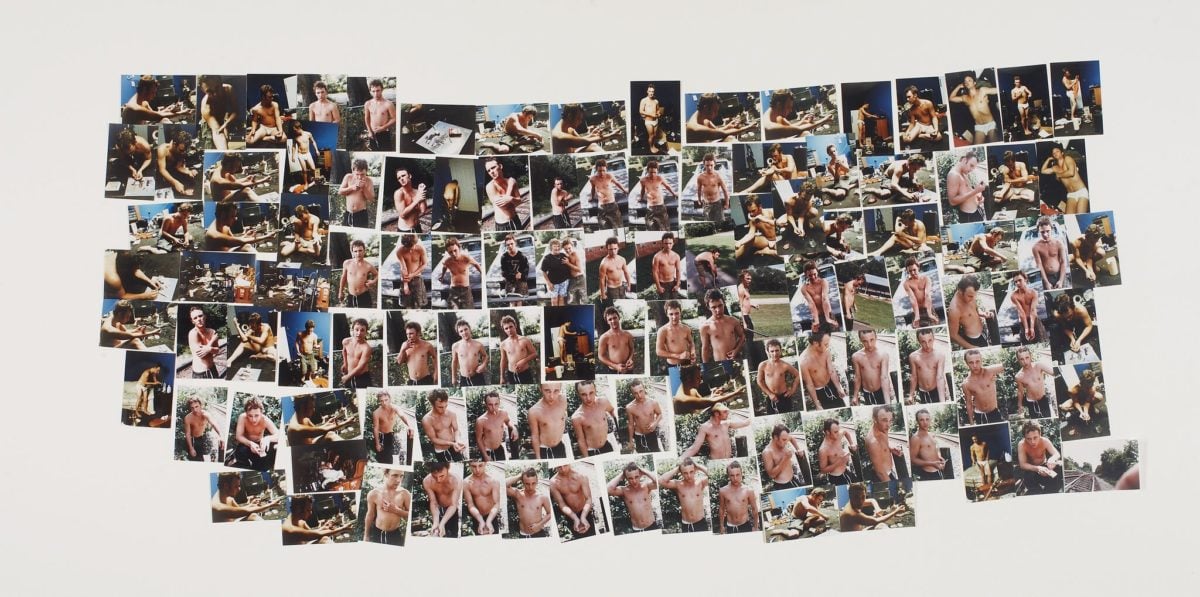

Larry Clark homage to Brad Renfro (2011). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

Would you say you’re an artist-photographer or a filmmaker?

I would say I’m an artist. I’ve never really thought of myself as a “photographer,” it just happened to be the tool I had in my hand. Back in the day, I used to wish I was a painter, a sculptor, a writer—I think I originally wanted to be a writer, or a filmmaker—but I had a camera so that’s what I used. The first work, Tulsa, is laid out like a film. It covers a continuous period, a cycle, and it’s like a circle. It begins with these kids, and it ends with other kids, and there’s very few words.

When I joined Luhring Augustine Gallery 26 years ago, I had said no to a number of photography galleries because I didn’t want to be in a gallery with a bunch of photographers. It’s obvious by now that I’m not just a photographer.

What is it that attracted you to the medium of film?

I’ve always been a storyteller, and I always wanted to make films, but I was just too fucked up for so many years living the outlaw life that I really had to clean myself up—to be able to have someone to give me a couple million bucks to go and make a film. So I really wanted to make film, and there came a time when I said, “Well, it’s now or never.” I cleaned up, got married, had a couple of children, and started really thinking about making a film.

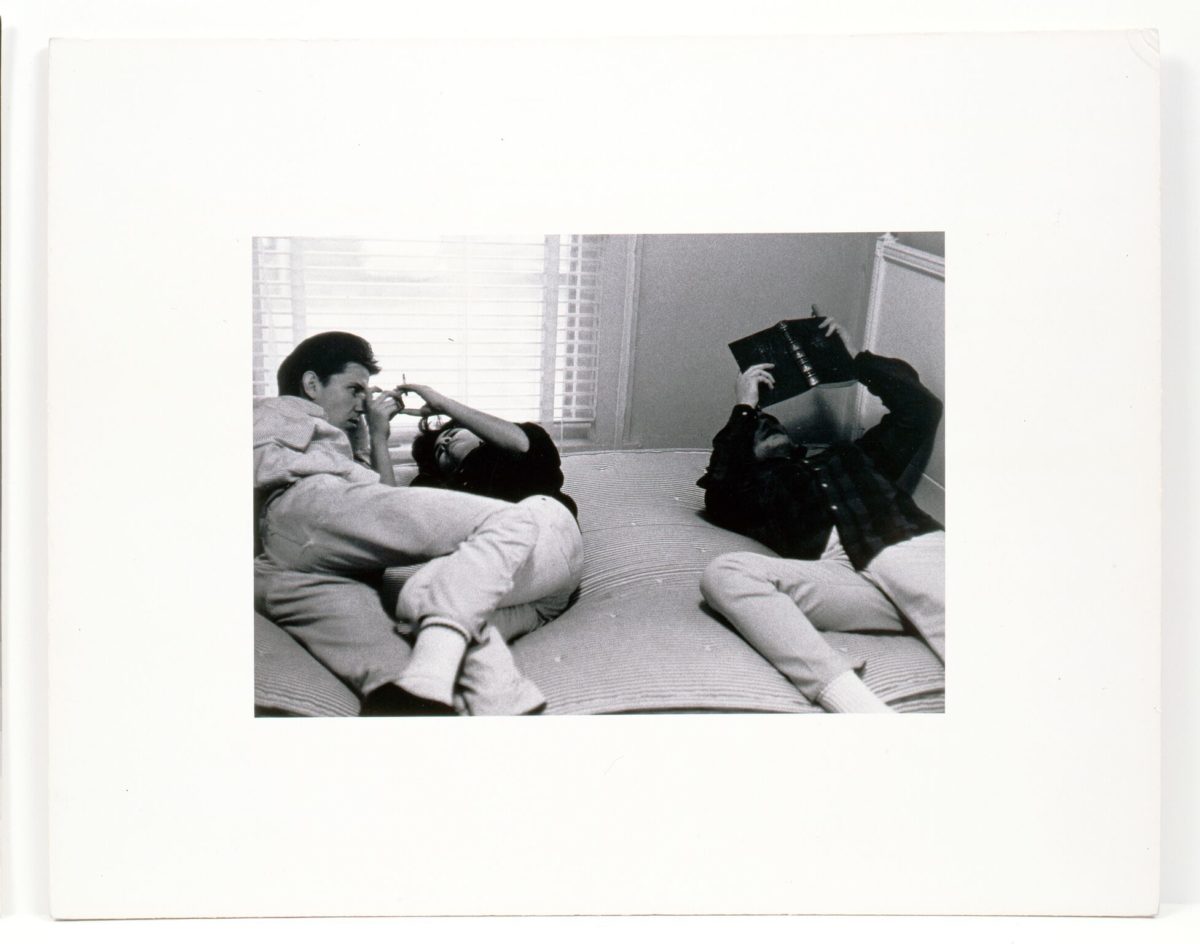

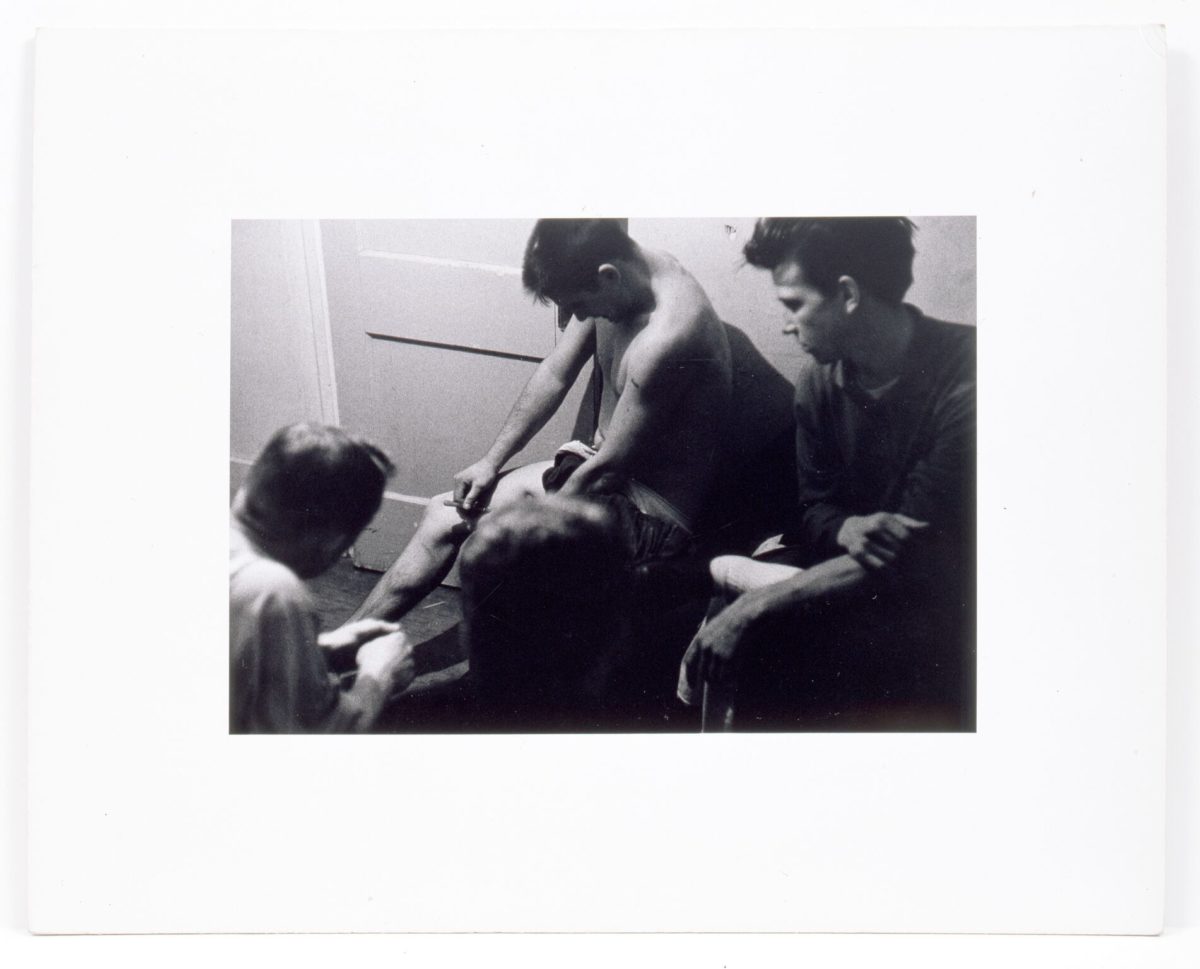

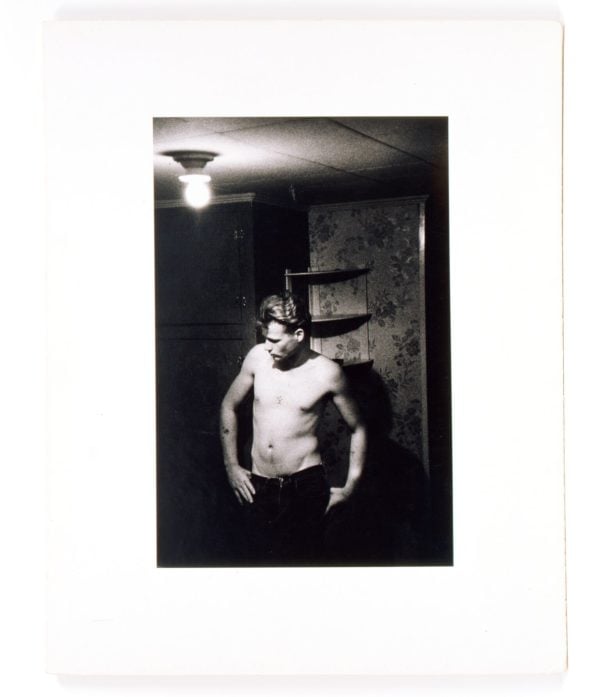

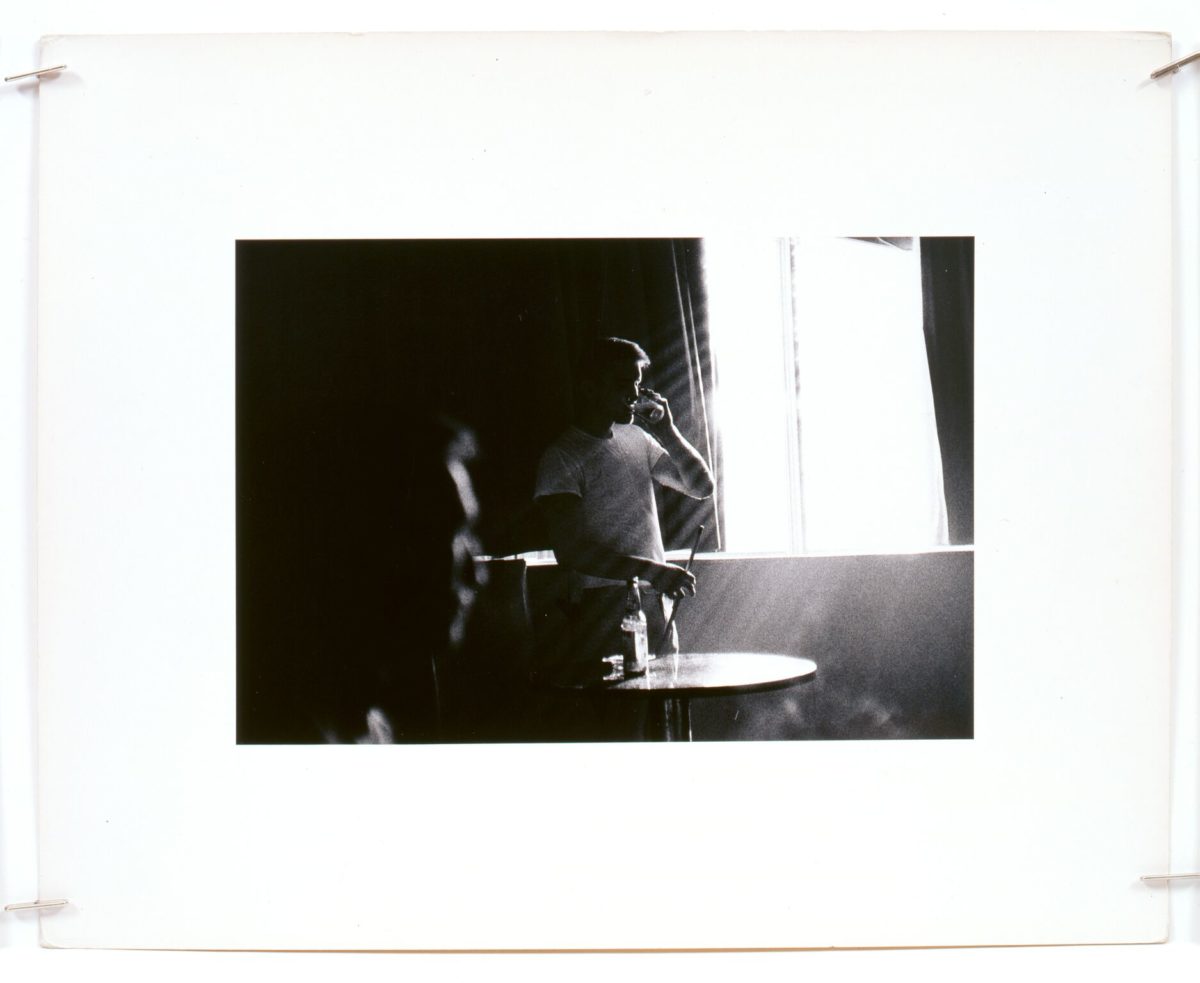

Larry Clark Untitled (1963). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

Do you think the medium of film, being multiple images, is superfluous given that a single image can captivate an audience?

No, there’s a slight difference. It was very hard to be a photographer, but nowadays everybody’s a photographer, everybody’s a filmmaker, everything has changed, and it’s a new world. But with film you can do more because people are moving, you can say a lot more in film.

What attracted you to depicting marginalized youths and youth culture?

I was a marginalized youth. I was one of the kids in Tulsa, and so I started showing what was going on from the inside. Nobody could have come in from the outside and photographed them or have been allowed to be with us. It was such a closed, secret world back then. It was so secret because it wasn’t supposed to be happening in America. But it was happening! It’s like you can’t photograph hell from the outside. It’s kind of like that. And then I just kept being fascinated by the way different kids were raised up in different situations and different environments, and it just kind of became my turf.

In the first film, when I made Kids … most of my early work had been autobiographical and I didn’t want to do that anymore. I thought I’d taken photography as far as I personally could take it. I wanted to make a film about the secret world of kids—where adults aren’t allowed—not unlike my world in Tulsa that was so secret.

Larry Clark Untitled (1963). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

I thought visually the most exciting kids were the skateboarders, and so I was drawn to them. I met some. And after a certain period of time, they let me in and treated me the way they treated each other. So I had to learn how to skate when I was 47 years old. If you’re gonna hang out with skateboarders and photograph them, you can’t run after them—you have to skate. I had to learn at a ridiculous age, and I really hurt myself, but I learned and got a lot of respect from the kids. That’s how the movie started.

It took a couple of years, but I finally had the story. Once I had the story, I needed a screenplay. But I always felt that something coming from the inside is better. I said, “Wouldn’t it be great if one of these kids could write the screenplay for me?” And I met Harmony [Korine], so it was serendipity or fate that we met. I gave him just a page of the story, and I told him this happens, that happens, this is the end; and he wrote a brilliant screenplay. I was very, very lucky. I’ve always been very lucky. Now I’ve made ten features and met people of all ages.

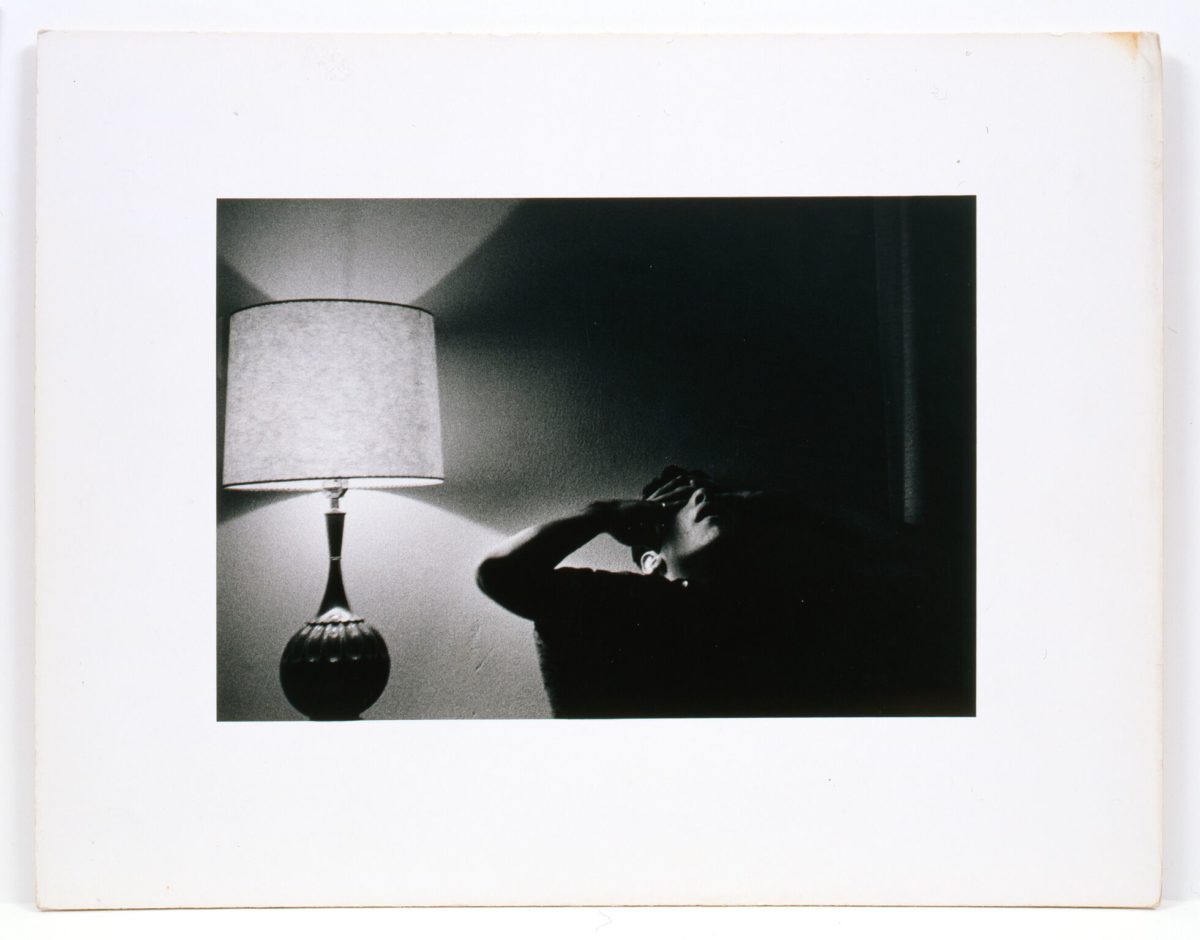

Larry Clark Heroin 6 (2014). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

What preoccupies you now? Are you still intrigued by counterculture and scenes of grit?

I think I’m just interested in the world and its people—and I’m very curious. I also just made a film in France, in French, about three years ago, and it came out in Paris a year-and-a-half ago. It’s quite good, I think—I just approved the English subtitles. There’s been the normal problems with distributors and people like that because they’re all crooks. In the film business, you have to be ready for that—knowing that everybody’s a crook. So it’s normal that the film’s been hung up, but we’re getting it back and it’s gonna be shown.

I like challenges. When I went to Cannes for Kids in ’95, I was talking to some French producers, actors, and directors, and I said, “I would really like to make a film in France about French youth.” And they said, “It’s impossible. You couldn’t possibly do it.” When I asked them why, they said “because you’re not French.” So it was kind of like a challenge, and 30 years later, I made the film—I never forgot that. Now I think I’m going to make a film in Mexico City in Spanish, hopefully. We’re trying to get that going. Then I have another big project in Paris coming up in the spring. A 24-hour podcast that I’m doing. We’ll be on TV 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for one week—so that’s gonna be interesting. I just try to keep working, keep busy, y’know?

Larry Clark Untitled (1963). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

Do you think that the narrative of your early work and Kids is still applicable to the youth of 2016?

Gee, I don’t know. Every generation seems to have seen the film. I was in a skate park recently with some skaters I know, and a 15-year-old kid came up to me and asked, “Are you sponsoring these kids?” And I said, “No, I’m a filmmaker, I make movies.” He said, “What movies?” And I said, “Have you ever heard of Kids?” And he gave me this disgusted look and said, “Everybody’s heard of Kids.”

Each generation has seen it, so I guess it holds up. They showed it at BAM a few months ago, and Chloë Sevigny, Rosario Dawson, and Leo Fitzpatrick—who were all in the film—and Harmony [Korine] and myself went. They showed Kids and we did a panel discussion and spoke to members of the audience. So it holds up I think, amazingly.

Larry Clark Untitled (1963). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

Your work is often graphic, shocking, and controversial. Is there anything you won’t document or show?

As an artist I never had rules. I never knew about rules. Because as an artist there are no rules, you can do anything that want to do. So there’s hardly anything that I wouldn’t film or photograph, except for child pornography or something like that.

There was a scene in this French film […] where this nine-year-old kid gets raped. It was very autobiographical. They were casting for a kid, and this one kid came in with his father, and I told him, “You have no idea what you’re getting yourself into because you’re nine years old. This movie comes out, and you go back to school, the kids are gonna be on you for the rest of your life.” And I told his father the same thing: “This is not something you want your son to be involved in.” I wouldn’t shoot it. Because of the circumstances, I rewrote the last chapter of the film myself. A lot of the things that I shot I threw out, and I rewrote the last half of the film.

It’s scary. I’m scared. I feel that when I’m scared it’s time to put it out. All my books have been that way. When it gets to the point where I’m afraid to let people see it, I always give them the ball.

Larry Clark Heroin 5 (2014). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

Do you think it’s still possible to be shocking and provocative in the digital media age, when everything is available on the internet?

I’m sure it is. It certainly is a different world with everything. One of the things that I wanted to show in the French film is how the internet gets kids in trouble. I was reading in the paper every day about kids getting into trouble when they go to a party. They have sex with a girl who’s passed out drunk. They do everything—and then they post it. Now kids will rob somebody, and then they’ll post it—posing with a gun and the swag in their hand, I mean it’s insane because it’s just so natural for them to post everything. The people that I know now that are in their 20’s automatically post everything they do. So I’m sure that there’s still things that can be shocking. But it’s shocking to me how everything is out there. Whatever is happening the kids will handle it, it’ll be fine. Everything will be fine.

Larry Clark Untitled (1963). Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

Would you say that you’ve always held a mirror to American society, to show it what it doesn’t want to see?

I’ve always been attracted to small groups that you wouldn’t know about, unless I made a film about them. I’ve photographed them from the very beginning. Like when I made the film in Los Angeles, Wassup Rockers, about these 13, 14, 15 year old Latino kids growing up in South Central, the ghetto, where no white people go. It’s all blacks and Hispanics in gangs. Everywhere, man. No white people.

I met these kids by accident. They took me to South Central, and I started photographing them. I ended up taking them skating every Saturday morning for a year-and-a-half. I’d go pick them up at nine o’clock, load them up in the car, and then take them all over Hollywood and LA and everywhere. Their world was pretty much six square blocks in South Central, so I opened it up for them. And I would listen to them tell stories all day—watch, and observe them. I would write in my diary, and after about a year-and-a-half, I wrote Wassup Rockers.

The first half of the film is their own stories, like a documentary, but it’s them playing themselves—but six months younger. In the second half of the film, they go to Beverley Hills, and it turns out it was much more dangerous there than it was in South Central—which is super dangerous.

You would never have known about these kids and the peer pressure on them to be like the blacks in the ghetto. The peer pressure for them was to wear baggy clothes, cut off their hair, listen to gangster rap, and stand on the corner, smoking pot. These kids wanted to grow their hair long, wear their clothes tight, listen and play punk rock, and skateboard.

In that film you see that everybody is afraid of the 14-year-old kids. It was amazing, man! I would take them around, and people were really afraid of them. They had on black t-shirts, and black pants, and were skateboarding, and were brown, and it scared people.

If you go to LA now you see thousands of kids like this. So the film influenced a lot of kids. Plus it influenced a lot of the black kids in South Central. The black kids growing up looked around and there were two ways to go: with the gangsters or with the skateboarders. So now they’re all these skaters. The kids in that film really changed the scene, so I’m happy about that.

But, yeah, I’m always drawn to small groups of people. I’ve always been drawn to that, and I still am.

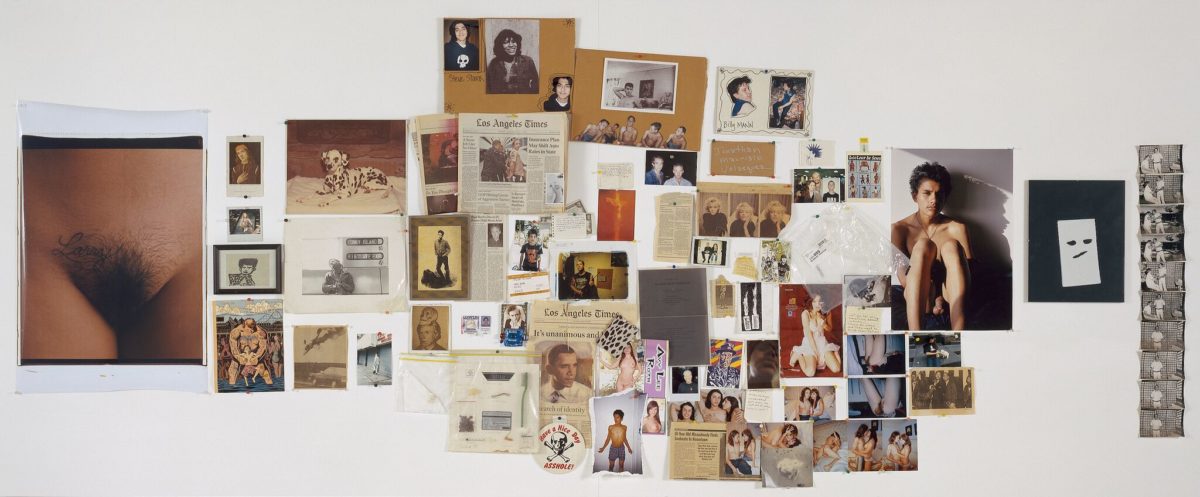

Larry Clark Untitled Collage. Photo: courtesy Luhring Augustine.

What are you showing at your upcoming exhibition at UTA in Los Angeles?

The show in LA is going to cover all aspects of my work. It’s interesting to me because I’ve never really shown my paintings, and people don’t really know me as a painter. And I’m showing photographs from 1961, the first series of pictures I ever took, as a teenager. And then some early material I made in 1963 from Tulsa, a Tulsa film that I shot in 1968 that’s one hour [long]. And it’s silent. It has only been shown in a couple of places. I showed it for the first time in Paris a few years ago for a big retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, and so we’re going to show that in a room on a loop.

At the show in the museum in Paris where we had the film, you walked in to see the photographs. Then there were these two really large gallery rooms where people would stop and watch the whole hour long film. And I’d watch the people watching. It was [shot] in ’68, and so you’d see the people from my first book alive. It’s going to be an interesting show. There’s going to be lots of different things going on.