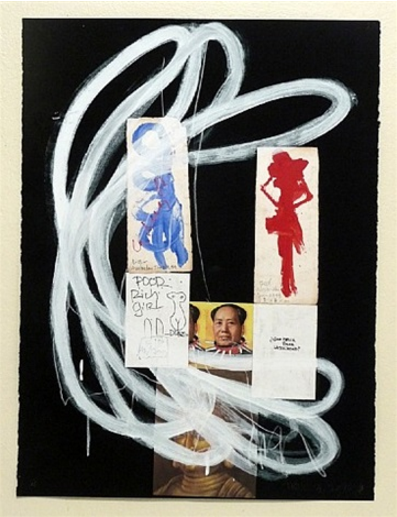

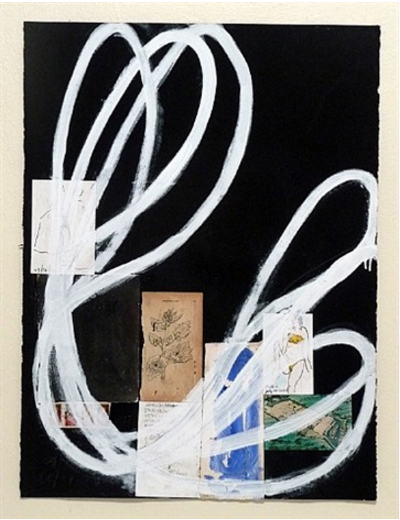

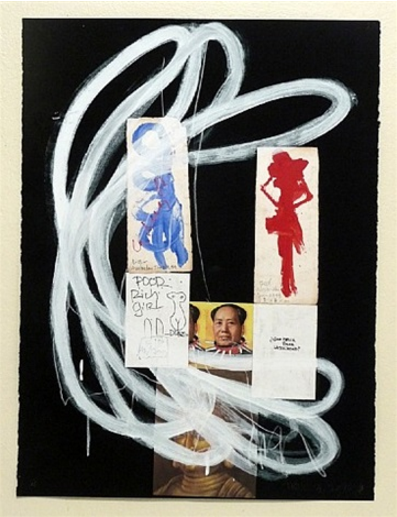

Raimundo Figueroa (1998–2001). Courtesy of the artist.

Raimundo Figueroa is one of those painters that can make the gestural and the slap-dash not only seem deliberate, but evocative, vital, and essential. You might not have heard of him yet, but you can expect to notice his name more and more as his work finds a greater foothold in the United States, as he is already more established in Central and South America, with his work already appearing in the collections of Mexico City’s Museum of Modern Art, Museo Tamayo, and the Museo de Arte Moderno in Sao Paolo.

Here, we had a chance to ask Figueroa about his artistic practice, collecting habits, and the importance of letting your paintings talk to you.

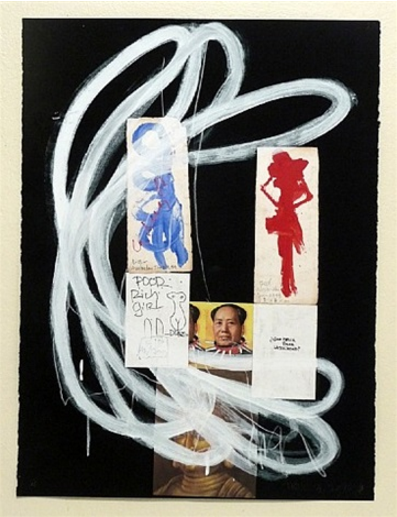

Raimundo Figueroa, Marshmellow (2012–2013). Courtesy of Space SBH.

Describe your creative process. What kinds of patterns, routines, or rituals do you have?

I dream most of my paintings. They are in my mind, and come out during my sleep. I think about painting quietly, and I do many drawings that are not a sketch of a painting—perhaps there are more than a dozen or two dozen drawings related to a particular subject matter—and then I start painting. But, the drawings are individual works, not reflecting the painting itself. Some icons may be part of the drawings and the painting at the same time—I am discovering, studying, sizing, and finally understanding subject matter, form, and color.

I see the works on paper as part of a whole group in the series. I like to explore the theme and subject in depth, and therefore that includes works on paper, drawings, collages, paintings, and sculptures.

Do you ever experience artist’s block? What do you do to overcome it?

No, I have not experienced such bad dreams—discipline does not give room to other action. I overcome all my lack of creativity by going back to basics: I think about drawing, the line, the form, and the color, how does this combination affect my daily life.

You mentioned that you are no longer in a collecting phase in your life, what is your reason for this? When you did collect, what did you like to collect and why?

After collecting actively over a period of more than 35 years, I have to evaluate how my life, taste, and knowledge have changed. What will I do with my collection? Who is going to take care of the works? What should I buy next? How can the collection be catalogued? And so on… Should I give it to a museum or create a foundation? These questions are on my mind constantly. As you may well know, we change as we grow in many directions. My taste is not the same in art as it was 30 years ago. I like young art, fresh with ideas that turned my head when I look at it, regardless of the media. I still buy art when I can, and my career as an artist permits me to contribute to the developing of the art market.

I collected in relation to my generation as an artist, and generations after. Previous generations were of major interest to me, of course, but the price tag was out of my pocket. I started out by collecting works on paper and multiples, then paintings, sculptures, and photography. Later on, I collected African “fetish sculpture” from Yoruba, Bakongo, Berber, Dogon, Songye, and other tribes. Today, I am most interested in discovering young artists for my collection.

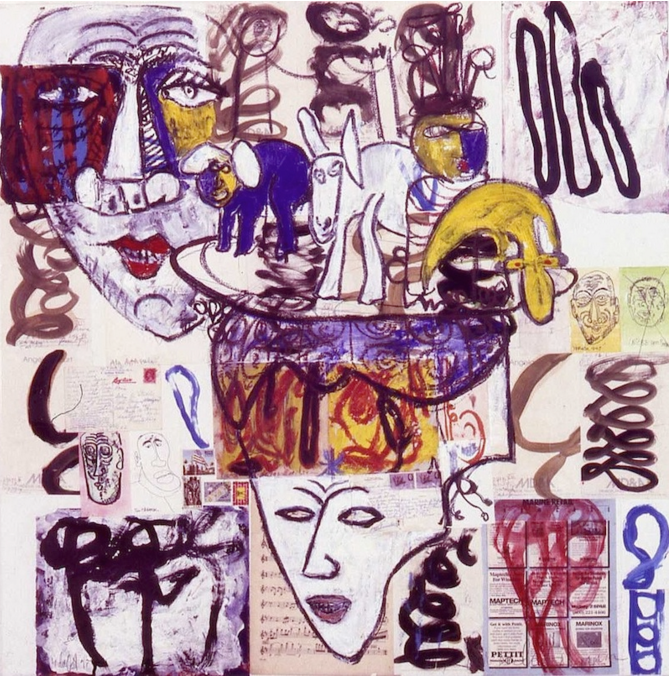

Raimundo Figueroa, La Congelacion de la Idea (2012–2013). Courtesy of Space SBH.

What do you think makes an artwork good?

The simplicity of reading it, capacity to communicate, the way it vibrates, the uniqueness of the idea. It is a given that it most be done with excellence.

How do you think the art world has changed since you first started showing work in galleries?

The Internet has changed all our communication habits, and that includes the art world. Everything has gotten closer via the cyber space.

When I grew up, the protagonist was the artist, the actor, the musician, the scientist, and the athlete, whereas today, the artist shares that protagonist role with art dealers, curators, museum directors, and art critics.

The art industry is not a regulated one, and due to the interest generated by the media it has turned into a very busy place. The gallery community has grown to an extraordinarily big one, and there are so many galleries and art fairs for discovering talent or following the trendsetters.

I feel that the most important change is that some intelligent gallery owners today are taking full care of the artist they represent, by making proper documentation of the creative process: books, catalogues, films, and historical archives are created for future generations to enjoy and study the artist.

What does an average day in the studio look like for you?

My day starts normally at 5:00 a.m. with coffee or tea, reviewing the day’s agenda, exercising, writing, drawing, and finally getting to the larger canvas. I play tennis almost every day—that keeps my mind fresh and organized. I like painting in the morning when my mind is not yet occupied with other matters. I use the late afternoons to communicate with the art world, with galleries, curators, dealers, collectors. I love finishing my workday with music.

How do you know when you are finished with a work or series?

There are some subject matters and themes that are ongoing in my mind, and therefore it makes a series based on such themes always unfinished. That is the case with the “Secret Dialogues,” a series I started many years ago and, little by little, transformed my relationship with own paintings through the dialogue with imaginary or real people. That is why some of these works have titles like; “Secret Dialogue with Plato and Cy Twombly on Infinites,” or “Secret Dialogue with Miles Davis, Mozart, and Robert Ryman on Solitude.”

The works are finished by the viewers. As I told you at the beginning of the interview, I normally dream my paintings, and there is a finish in the dream that I then have to reproduce. I never achieve the quality of my dream. When one is submerged totally in creativity from the very first light of the day, one goes to sleep thinking of your work. It has a flowing action. That is discipline in creativity.

I never discuss my work when in process, since I don’t want another mind involved in my own work. I don’t show work in progress to others. I know when work is finished when I don’t see the need to keep going to it and adding more. Lately, applying layers of pigment to create surfaces and transparency has taken longer than expected, and at the end I am never ever in a hurry. I like hanging around my paintings to see how they talk to me: I put them upside down, sideways, and back to normal. Finally they talk back to me, and I can see the story.