Pop Culture

As Seen on ‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off’: Seurat’s Pointillist Triumph

Director John Hughes once dubbed the movie his "love letter" to Chicago. A scene at the city's museum bears out that affection.

John Hughes’s beloved 1986 film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off follows three students, Ferris, Sloane, and Cameron (Matthew Broderick, Mia Sara, Alan Ruck), as they skip school and spend a wonderful day in Chicago. That’s it. That’s the movie. Sure, there are occasional sour notes here—Cameron, for one, can’t stop fretting about them stealing off in his father’s car—but nothing that dampens the trio’s romp through the city. Why worry? Life already moves pretty fast, don’t you know?

So, with class cut, the threesome roll into Chicago in a borrowed Ferrari, finesse a table at a fancy restaurant, attend a baseball game, and, in the film’s climax, gatecrash a float at the Von Steuben Day Parade. In between, Ferris persistently breaks the fourth wall to drop bon mots like: “Only the meek get pinched. The bold survive.”

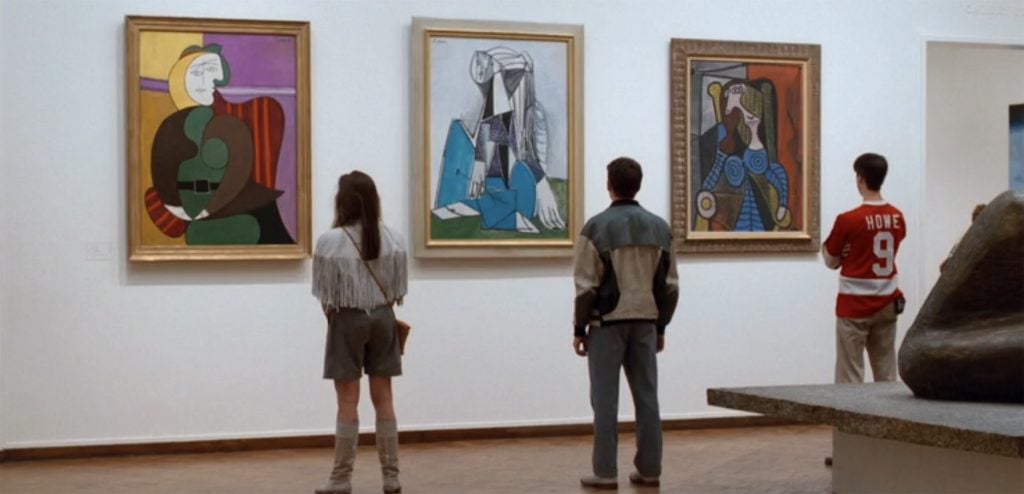

Amid the hijinks, the gang spends a relatively quiet interlude at the Art Institute of Chicago, taking in artworks by the likes of Hopper, Picasso, Pollock, and Giacometti. It’s a wordless sequence: Ferris and Sloane make out beneath Marc Chagall’s American Windows (1977), while Cameron has a moment with Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884).

Mia Sara, Matthew Broderick, and Alan Ruck in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). Photo: Screen grab.

The late Hughes once dubbed Ferris Bueller his “love letter” to Chicago, and this scene in the museum bears out that affection. The camera lingers on paintings as the score swells with surprising tenderness.

Speaking on the film’s DVD commentary, Hughes called the sequence “a self-indulgent scene of mine,” and the museum “a place of refuge for me… This was a chance for me to go back into this building and show the paintings that were my favorite.” (It marked the big-screen debut of the Art Institute of Chicago, too.) Actor Jennifer Grey, who plays Ferris’s sister, also recalled the director telling her, “There are going to be more works of art in this movie than there have ever been before.”

Alan Ruck in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). Photo: Screen grab.

In particular, the Seurat work is showered with special attention, its Pointillist detail intercut with Cameron’s questioning face. His meeting with the painting appears to roil up emotions in the teenager, whose angsty relationship with his father, we learn, has shaken his confidence. “I can’t handle anything—school, parents, the future,” he tells Sloane.

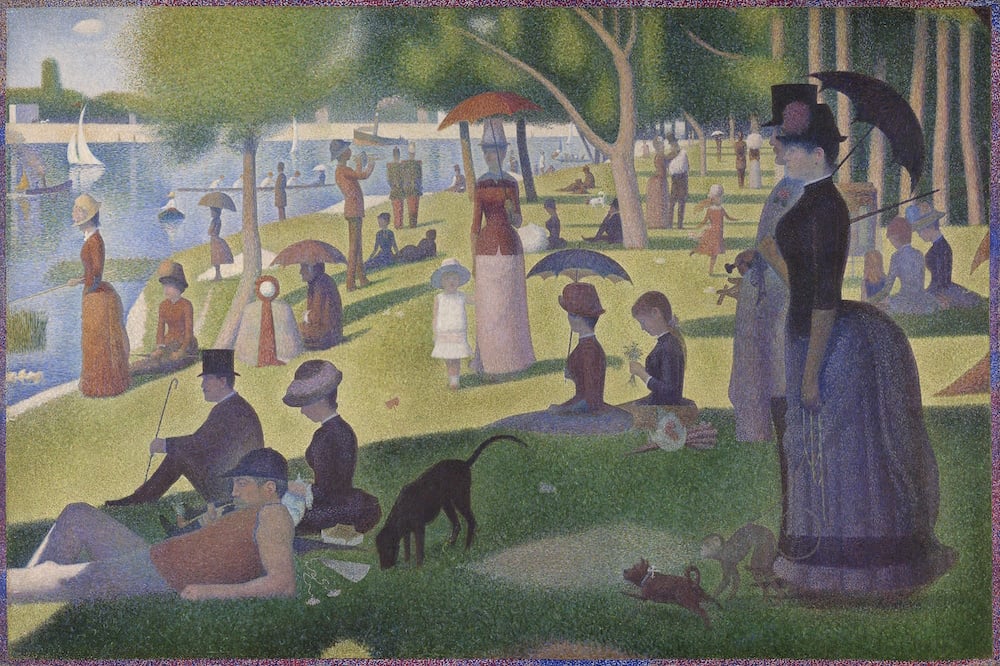

Against Cameron’s anxiety, Seurat’s masterwork offers a serene, almost sedate, counterpoint. The French painter famously spent years meticulously arranging the composition, then executing it with a technique that enhanced its light and color. While most of the figures in the scene gaze tranquilly toward the left at the River Seine, a single girl is depicted facing out, toward the viewer, with an inscrutable gaze. It’s her face that Cameron is fixed upon.

Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–86). Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

“The more he looks at it, there’s nothing there,” Hughes said of the character’s encounter with La Grande Jatte. “He fears that the more you look at him, the less you see.”

Indeed, as the camera closes in on Seurat’s painting, its forms grow indistinct. “I always thought this painting was sort of like making a movie, the Pointillist style,” Hughes reflected. “You don’t have any idea what you’ve made until you step back from it.”

It’s a sentiment that won’t be lost on our protagonist, who, throughout the movie, simply refuses to sweat the small stuff. Life, in Ferris’s immortal words, passes us by fast. “If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”