Pop Culture

As Seen on ‘The Crown’: A Churchill Portrait Despised by Its Sitter

The work was destroyed within a year of its unveiling.

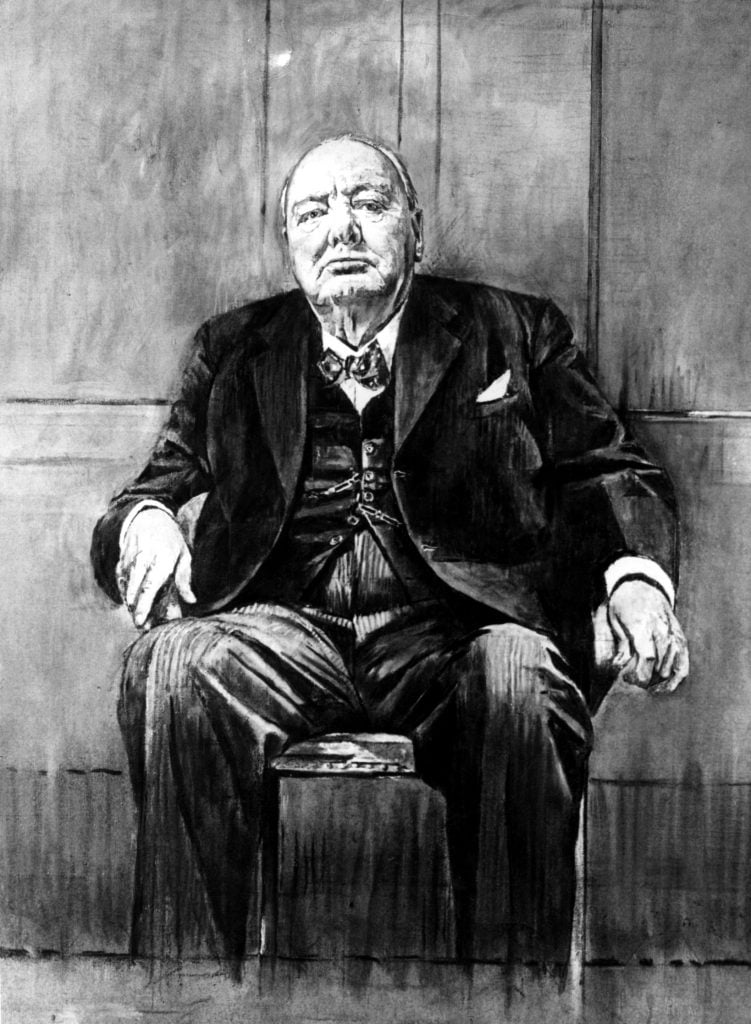

This June, Sotheby’s London is offering a portrait study of British icon Winston Churchill by Modernist artist Graham Sutherland, with a high estimate of £800,000 ($995,000). In the painting, said Andre Zlattinger, Sotheby’s head of modern British and Irish art, “Churchill is caught in a moment of absent-minded thoughtfulness, and together with the backstory of its creation, it gives the impression of a man truly concerned with his image.”

Graham Sutherland’s portrait study of Winston Churchill at Blenheim Palace, the U.K., 2024. Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Sotheby’s.

Zlattinger isn’t kidding when he says Churchill was concerned with his image—the painting would not survive its first year. And it does harbor a hell of a backstory from its creation to its eventual destruction, which was depicted in the season one episode, “Assassins,” of the hit Netflix series The Crown. Over six seasons, the Emmy- and Golden Globe-winning historical drama spanned six decades of British history, from the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten to the marriage of Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles in 2005.

Churchill, himself an accomplished painter, was no fan of the painting, commissioned by the House of Commons and the House of Lords. “It makes me look half-witted, which I ain’t… Here sits an old man on his stool, pressing and pressing… I look like a down-and-out drunk who has been picked out of the gutter in the Strand.”

The painting was unveiled on a grand occasion marking Sir Winston’s 80th birthday, the entire proceedings broadcast on national television—an event recreated in The Crown. Churchill’s audience laughed when he pronounced his public assessment, archly calling the painting “a remarkable example of Modern art.” While Churchill can hardly keep from laughing after delivering the line, Sutherland’s hand rises to his face in humiliation.

Still from The Crown, season one, episode nine (2016). Photo: Netflix.

The painting was delivered to the Churchills’ home and promptly vanished from public view. The family would later reveal that the portrait had been destroyed within the year, supposedly by Churchill’s wife Clementine. Sutherland later called the destruction of the work an “act of vandalism.”

On The Crown, John Lithgow plays the prime minister, while Harriet Walter portrays Clementine and Stephen Dillane plays Sutherland. The episode follows the tense negotiations between artist and subject about how Churchill will be portrayed. “I paint a bit myself, you know,” said Churchill, seeking a flattering portrait, “and I never let accuracy get in the way of truth if I don’t want it to.” In the explosive confrontation between the two men after the unveiling, Sutherland defends himself: “If you’re engaged in a fight with something, then it’s not with me! It’s with your own blindness!”

Graham Sutherland’s portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, unveiled on November 30, 1954. Photo: NCJ – Topix/Unknown/Mirrorpix via Getty Images.

Speaking at a 2015 conference organized by the Telegraph, historian Sonia Purnell, author of the 2015 biography First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, explained that Madame Churchill would have seen it as her duty to suppress the painting.

“Clementine’s work, in the last few years of her life, was all about protecting [Churchill’s] legacy,” she said. “When his career was no longer important, it was his legacy that counted. Just as she was fastidious in promoting his career, so she did the same with his legacy. She saw that painting as not being the kind of heroic, warrior statesman kind of image she wanted to project. So she was ruthless about it; it had to go.”

New evidence emerged in 2015 that Lady Churchill’s private secretary, Grace Hamblin, was the one who actually torched the canvas.

Purnell recounted the conversation between Hamblin and Clementine Churchill. “The next day, she told Clementine what she’d done,” she said, “and Clementine said: ‘We’ll never tell anyone about this because after I go I don’t want anyone blaming you. But believe me, you did exactly as I would have wanted.’”