Pop Culture

As Seen on ‘What We Do in the Shadows’: A Vampire’s Centuries-Old Portrait

The work recalls a real portrait of a historic Persian ruler.

Hulu’s comedy series What We Do in the Shadows follows the 760-year-old vampire Nandor the Relentless (played by Kayvan Novak), once a general of the Ottoman Empire, now residing in Staten Island. With his roommates—all fellow vampires—Nandor embarks on misadventures in the modern world, best depicted in season one when he leads his compatriots on a mission to “take over” the borough, involving hijinks and local council politics. Age has softened him, though, rendering him less arrogant and almost sweet in his septi-centennial years.

But his fearsome past is revealed in bits and pieces—and through artworks. Nandor’s homeland is Al Qolnidar, a fictional 13th-century state in contemporary southern Iran. We learn that during his tenure as terrible army general, he pillaged innumerable villages, twice turning the Euphrates red with blood. “People would say, ‘Please don’t pillage me,'” he recalls. “And I would say, ‘No, I’m pillaging everyone, you included!'”

Kayvan Novak in What We Do in the Shadows (2019–). Photo: Screen grab.

In the show’s pilot, he admires a patina-ed portrait of himself painted in a traditional Islamic style. In it, he is depicted sitting atop his beloved horse, Jahar. The portrait is a typical example of real-life historical portrayals of Ottoman Emperors.

One such emperor is Karim Khan Zand, founder of the Zand dynasty that ruled Persia from 1751 to 1779. His horseback portrait very likely served as the source for Nandor’s in the show. Under his rule, Iran found peace and prosperity, recovering from the devastation of 40 years of war. The painting is attributed to the artist Abu’l Hasan Ghaffari Mustawfi Kashani, who completed the work in the style of the later Safavid artists, likely during Karim Khan’s reign.

Portrait of Karim Khan Zand on horseback. Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

Karim Khan’s backstory doesn’t quite match Nadnor’s. Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, however, who reigned from 1797 to 1834, is more Nandor’s equal. During the first and second Russo-Persian Wars in the first quarter of the 1800s, Fath-Ali was notorious for invading and pillaging Georgian towns. Also similar to Nandor, Fath-Ali was extremely prolific. With a 1,000-woman-strong harem, he sired 57 surviving sons, 46 surviving daughters, 296 grandsons, and 292 granddaughters.

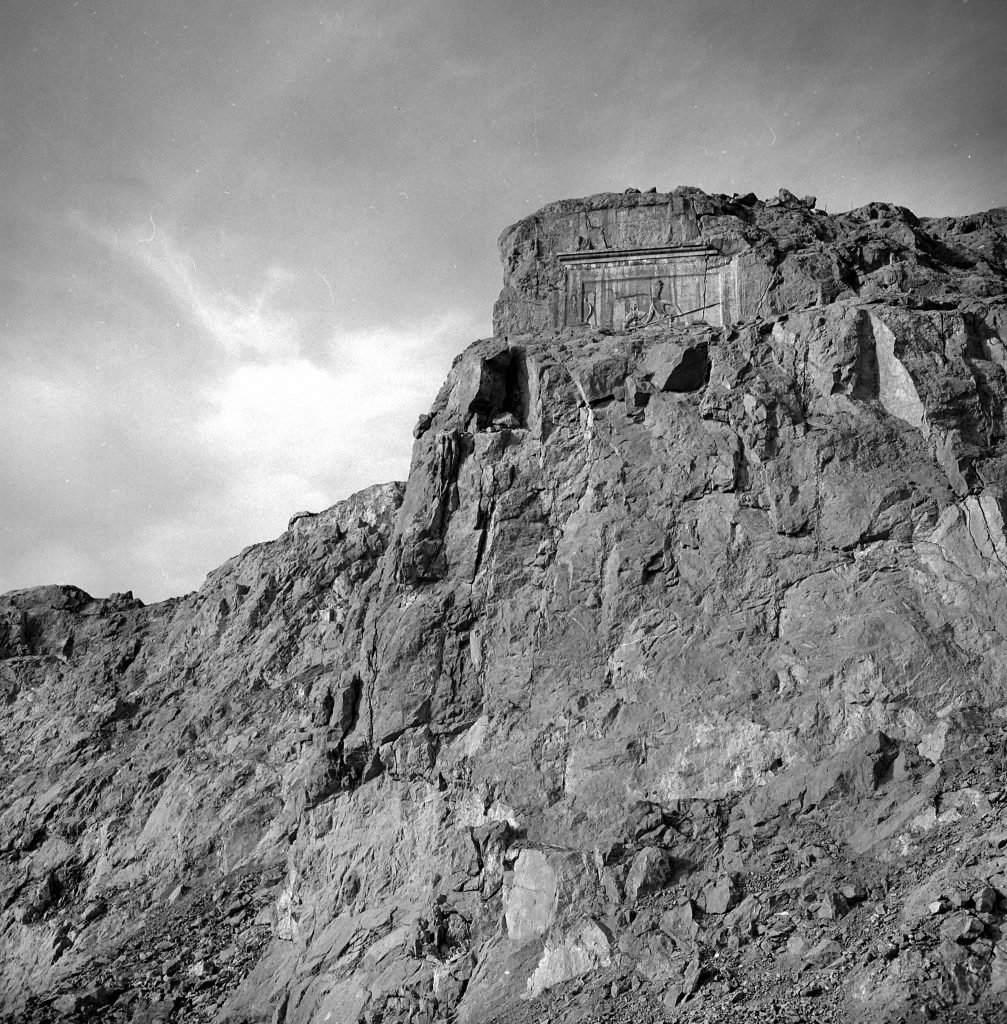

Under his rule, several visual portrayals of Fath-Ali Shah and his court were created as a concerted effort to iconize the crown. Seven of the Qajar rock reliefs, monuments in Iranian art, were commissioned during his time in the pre-islamic Iranian cities of Ray, Fars, and Kermanshah. The reliefs were essentially political propaganda, artistic attempts to solidify his legacy as heir to the ancient Persian empire in the eyes of country folk.

Rock relief depicting Shah Fath Ali at a lion hunting in Qajar (XIXth century). Photo: Roger Viollet via Getty Images.

In the opening credits of What We Do in the Shadows, another regal portrait of Nandor from his human years is on display. In it, he stands authoritatively, dressed in a gold brocade robe with a fur-trimmed sleeveless vest of sorts and a high turban. The painting is an almost exact replica of Portrait of Mirza Abu’l Hasan Khan, Envoy Extraordinary from the King of Persia to the Court of King George III, made by British artist William Beechy in 1809.

Still from the credit sequence of What We Do in the Shadows (2019–). Photo: Screen grab.

Much like Nandor’s assignment to his New York borough, Mirza Abu’l Hasan was Fath-Ali Shah’s ambassador to London. Though he only lived in England for less than a year, the ambassador quickly became an object of fascination and the subject of paintings and poetry. There might be a chance yet for Nandor to follow in Mirza Abu’l Hasan’s footsteps and become the muse of Staten Island.

As Seen On explores the paintings and sculptures that have made it to the big and small screens—from a Bond villain’s heisted canvas to the Sopranos’ taste for Renaissance artworks. More than just set decor, these visual works play pivotal roles in on-screen narratives, when not stealing the show.