Art World

How Do I Write a Statement About My Exhibition That Isn’t a Total Cliche? Art Professionals Offer Real, Actionable Advice

Hint: read other good writing, be original and find a good editor.

Hint: read other good writing, be original and find a good editor.

Francesca Gavin

When presented with a blank page on which to write their exhibition text, many artists will respond with one strong emotion: horror. However, the process doesn’t have to be so painful. There are many ways to reflect an artistic practice or a body of work through a piece of writing—interviews, poems, lists, creative essays, glossaries. And in the worst case, there is always the well-chosen quote.

Olivia Radonich, of the gallery ReadingRoom in Melbourne, recommends an intuitive approach. “Read poetry! Don’t compromise. Don’t write press copy. Don’t follow a format. Be vulnerable, be open,” she advises. “Try to get to the heart of what compels you to make work, and share that. Getting to that place, close to it, capturing it and bringing it into focus can be difficult, so use whatever format helps capture that feeling: talk with someone you trust, read widely to find examples of what moves you, keep text messages, voice notes, writing on scraps of paper, notebook.”

Radonich recalls an experimental text the Melbourne-based artist Emma Phillips wrote for her 2019 show. “Emma used a bricolage approach to assembling her exhibition text; it was very grueling watching her refine each draft; the result was layered, complex, funny, haunting and poetic. It revealed so much about her subjects, her way of working and her chosen medium for that particular exhibition—photography, specifically very intimate large-scale portraits.”

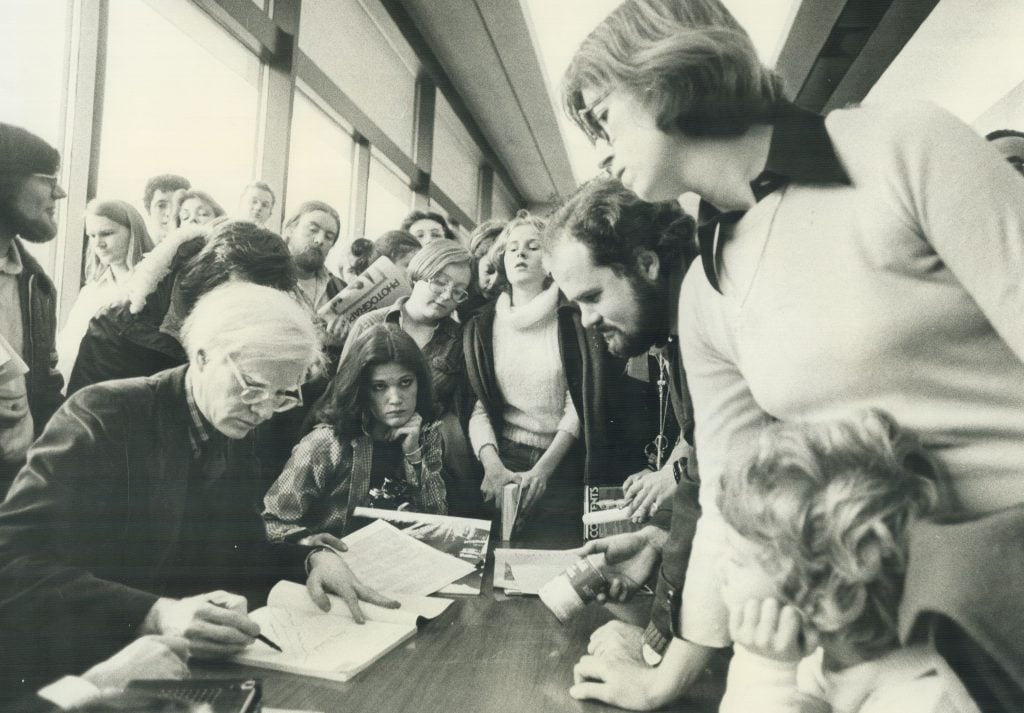

Staged between the cubicle-like glass partitions of Brookfield Place’s atrium, in downtown Manhattan, Ernesto Pujol’s performance 9-5 (2015) paid homage to city office workers. © Nisa Ojalvo 2015.

The artist Sam Jablon, who also has an academic background in poetry, finds working alongside someone else can help. “Have a good editor who you can bounce ideas off, and write something that explains the show without over-explaining it,” he says. He also recommends describing the work rather than relying too much on a theoretical angle. “The purpose of a text is to create an entry for people into the work,” he says. “It’s like an introduction to the ideas behind the show.”

Christian Egger, a Vienna-based visual artist and author whose book of collected criticism is published by Floating Opera Press, agrees that it can help to ask another writer for input. “Someone who follows your work, who is a writer and not necessarily within the field of art,” he says. “Somebody who might be able to lay new tracks or contextualize, deconceptualize or just misunderstand everything—but in an interesting way.”

Originality should be the aim of any writer. “Avoid dialectics and stereotypes, instead go for the mythic, surprises, hilariousness and ahistoricism,” he adds. “I am always allergic to opening lines such as, ‘Artist X is…’ or enumerations of what is in a show. Also, predictability of references can be annoying.”

Egger suggests looking at how some great artists have approached the job, citing Claire Fontaine, Pauline Boudry/Renate Lorenz and the defunct London collective BANK as good examples. “Back in the early 2000s, the creative collective Reena Spaulings serialized and distributed extracts of their bootleg translation of Situationist Michèle Bernstein’s 1959 novel Tous les Chevaux du Roi during exhibition openings at their gallery in New York,” Egger adds.

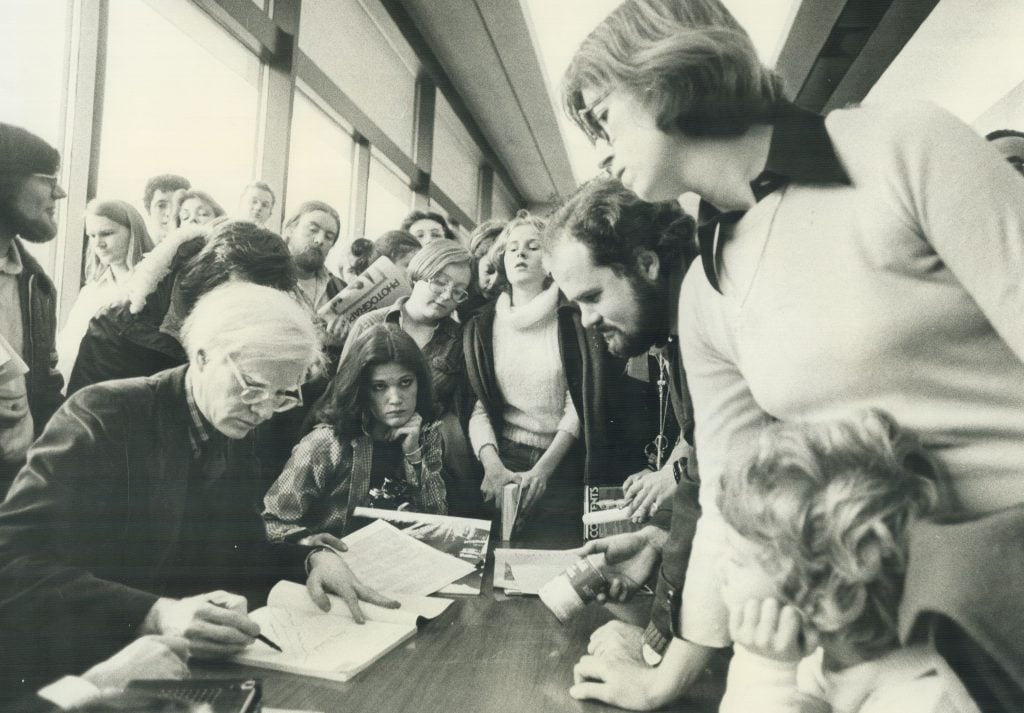

Tim Youd retyping Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar at the Armory Show, New York, for “100 Novels.” Photo courtesy of Cristin Tierney Gallery.

For those still stuck, one suggestion is to collate a collection of existing texts and examine their approach. In some cases, you’ll notice there is a formula to writing. You’ll see it in every paragraph in a good newspaper. The first line is a statement. The next two or three lines expound on that initial statement. The last line is a conclusion. It can be that basic.

Historic, scientific and literary references or events can also be good openings to ground a show. And when in doubt, just start with a question?

The central thing is not to stress, since half the time, people take the papers they pick up at an exhibition and stick them in their pockets, or just throw them away. “The text is the companion” rather than the main event, Radonich notes. It is just another way to bring an audience in. And as Jablon points out, that audience can widely vary, with the general art-loving public joined by press, collectors, curators, and other artists. Remember, the exhibition text is, Jablon says, just “breadcrumbs to follow.”