People

‘I Find Freedom in Constraints’: Aura Rosenberg on Making Art That Transgresses the Bounds of History, Sexuality, and Memory

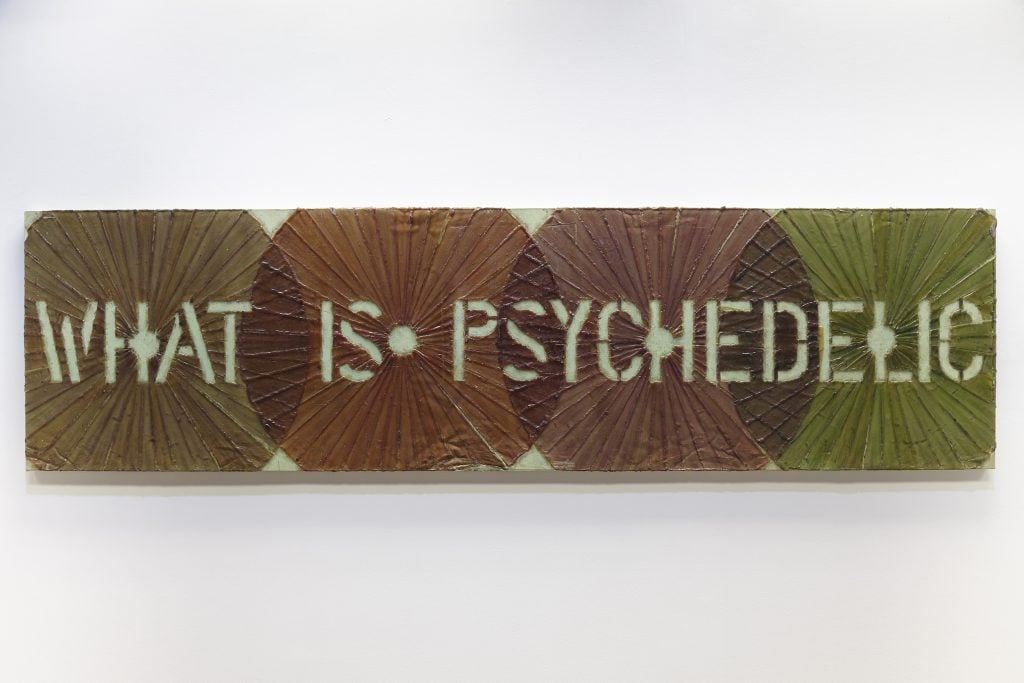

The artist's two-venue survey, 'What Is Psychedelic,' runs through June at Mishkin Gallery and Pioneer Works.

The artist's two-venue survey, 'What Is Psychedelic,' runs through June at Mishkin Gallery and Pioneer Works.

Meka Boyle

Throughout her groundbreaking five-decade career, Aura Rosenberg has built an idiosyncratic vocabulary of references and ideas. Themes from sexuality to history to motherhood push up against each other in dynamic ways, exposing underlying tensions. Now for the first time ever, her oeuvre comes together in an institutional survey. The two-venue exhibition, “What Is Psychedelic,” opens this month at Mishkin Gallery and Pioneer Works.

“What Is Psychedelic” follows the New York- and Berlin-based artist’s expansive trajectory and features previously unseen works. The survey is accompanied by an eponymous publication dedicated to Rosenberg’s practice—another first. The monographic reader features essays old and new by a range of writers, artists, and curators including Lena Dunham, Laura López Paniagua, and John Miller.

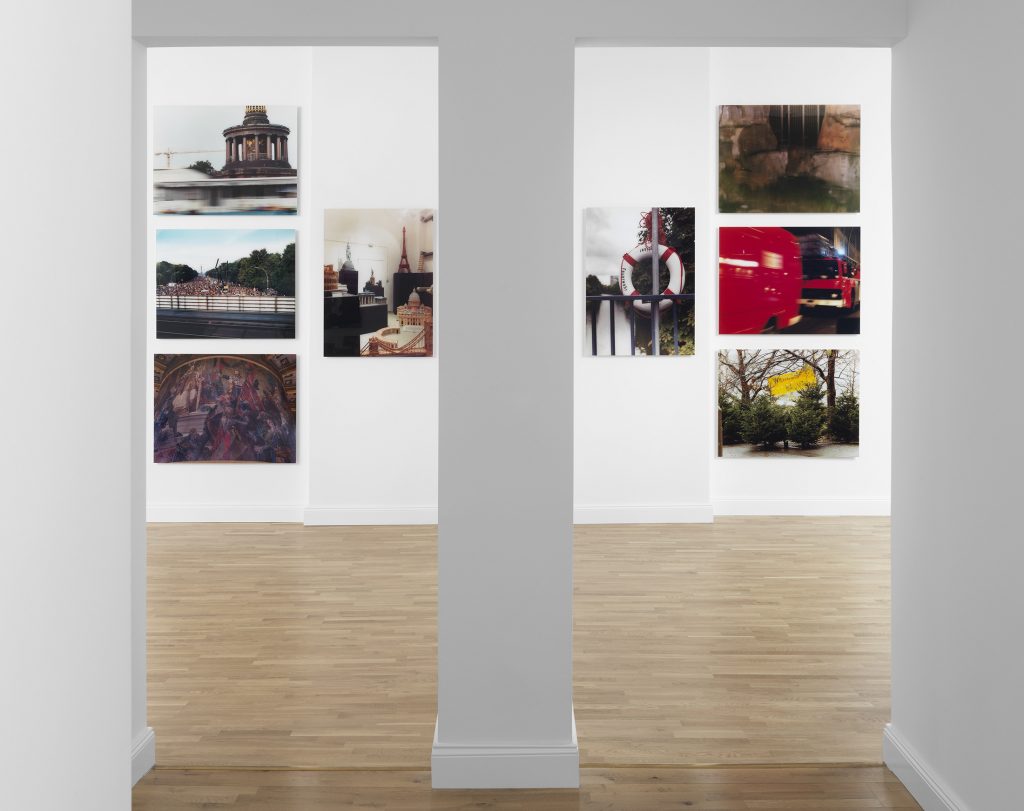

Installation view of “Aura Rosenberg: What Is Psychedelic,” Mishkin Gallery, 2023. Photo: Isabel Asha Penzlien.

The exhibition is a homecoming of sorts for Rosenberg, who found her footing as an artist in New York in the ‘70s alongside her peers Marilyn Minter, Laurie Simmons, Mike Kelley, and her husband John Miller. Her early image-text paintings rearranged formal ideas of modernism to create a new visual language; her boundary-pushing series “Dialectical Porn Rocks” in the late ’80s ignited her lifelong exploration of the dialectic between high and low.

When Rosenberg moved to Berlin in the early ‘90s, she discovered a kindred spirit in the late 19th-century German philosopher Walter Benjamin. She created a visual companion to Benjamin’s memoir Berlin Childhood by photographing her surroundings, the city of Berlin, and her daughter Carmen; later she began an ongoing collaboration between the philosopher’s granddaughter and great granddaughter.

Installation view of “Aura Rosenberg: What Is Psychedelic” at Mishkin Gallery. Photo: Isabel Asha Penzlien.

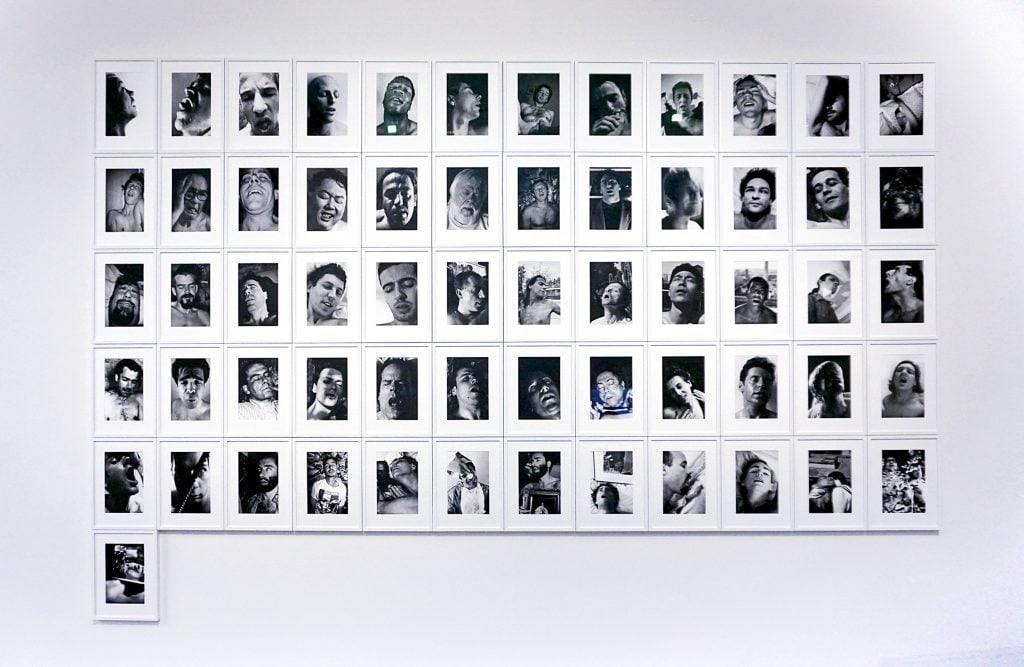

Over the years, Rosenberg has referenced everything from the Golden Age of Porn to Classical sculpture to critical theory. She nimbly examines ideas around gender, family, sexuality, history, popular culture, and memory. While the subject matter varies, her work is always grounded in everyday life. It is also inherently collaborative. In “Who Am I? What Am I? Where Am I?” Rosenberg paired her daughter and her peers with artist friends to produce moving, and at times controversial portraits. When a male critic wrote of her work as exploitative, she subverted the male gaze with “Head Shot,” a series where she collaborated with the male subjects including the artists John Baldessari and Mike Kelly to stage portraits mid-orgasm.

A multidisciplinary artist through and through, Rosenberg moves fluidly between painting, photography, film, sculpture, performance, and installation; she often combines all of these mediums within a series. It goes without saying that most of Rosenberg’s projects are ongoing. Even the series that have end dates affixed to their titles are fair game for revisiting, if and when she feels inspired.

Installation view of “Aura Rosenberg: What Is Psychedelic” at Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica, courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Rosenberg’s oeuvre is difficult to categorize upon first attempt, her subject matter seems incongruent on the surface level. Upon closer look, “What is Psychedelic” reveals a multitude of connections; binaries become slippery as layers unfold. As she prepares for the survey, she is more interested in what interpretations others will make from her work than identifying these connections on her own.

Below, Rosenberg sat down with Artnet News to discuss her work, her life, and the fertile space in between.

Aura Rosenberg, “Dialectical Porn Rock” (1989–93). Photo courtesy of the artist.

When you first began working with pornographic images in your “Dialectical Porn Rock” series, porn was still on the fringe and depicting sexuality in art was considered shocking and provocative. What drew you to this?

When I started working with porn imagery in the late ’80s, I wanted to do something provocative. The work of John Miller, now my husband, and Mike Kelly, his close friend, inspired this approach. Their work was transgressive, and I wanted to do the same. This led to my first photo series, “Dialectical Porn Rock.” Here, I took images from porn magazines, decoupaged them onto rocks, then photographed the rocks in various landscapes. Twenty years later, when I revisited that work, the magazines I took clippings from had ceased publishing. When I searched for similar pictures online, I discovered that the images I used had come from what now was called the Golden Age of Porn, a period roughly from the ’70s until the AIDS crisis. It was a time when porn went mainstream. Photographers staged porn shoots in high-class homes. In the background, surrounding the porn stars were all the accoutrements of culture: books, wine on the coffee table, plants, little statues. Perhaps they were staged this way to make them seem like art films and avoid censorship.

Making the porn rocks also made me more aware of the long history of figurative stone statues. The desire to make stone into flesh goes back at least 30,000 years to the Venus of Willendorf. I started to see the Dialectical Porn Rocks as ready-made figurative sculptures.

Once you took this idea and drew it out, did you find that there was more to it?

Yes. As I photographed the rocks in landscapes, I began to see a certain poetry and pathos to these bodies. The naturalness we usually associate with sexuality was highly mediated, as were the surrounding landscapes. For example, I photographed porn rocks over the Grand Canyon, an area designated as natural for us but one which must be actively maintained as a nature preserve. When we moved to Berlin, I placed the altered rocks in historical locations like Marx-Engels-Platz or at the site of the Berlin Wall. These locations felt threatening and suggested bodies under state control. So, the provocation of this series accrued significance beyond its initial shock value.

Aura Rosenberg, “Berlin Childhood” (1996–ongoing). Photo courtesy of the artist.

After you had your daughter you transitioned to other material and worked on two long-term projects involving childhood: Berlin Childhood and “Who Am I? What Am I? Where Am I?” How did your practice evolve in relation to your life?

I didn’t explicitly decide to stop working with porn because of my daughter—it was more that I became involved with projects that grew out of motherhood. I was immersed in raising a child and that, of course, shaped my work. In ’98, I showed “Who am I? What am I? Where am I?” a series of collaborative portraits of children, for the first time. The idea came from face-painting, something children typically love to do at school fairs. I would invite another artist to paint a child’s face. Robert Mahoney reviewed my show, writing, “Are you a woman artist? Are you a mother? Are you pressed for time? Well, make your art out of your kid. Problem solved for the art, but what that says about the state of modern motherhood is another thing.” He went on to rip my work apart. For instance, he said Laurie Simmons had become so ego-crazed that she turned her daughter into one of her puppets, not knowing that the photo was Lena’s idea. Lena calls it her directorial debut.

“Who am I? What am I? Where am I?” was really about giving artists the opportunity to play while giving children the opportunity to express their fantasies. I think of my work as good-natured, but what often happens, even with the best intentions, is that it also exposes underlying tensions.

I also think that reaction reveals more about broader cultural fears and obsessions around sexuality and youth. It also feels inherently sexist that making art about your child was framed as a bad thing when it is nothing new that artists draw from their lives for inspiration. How did you respond?

Women artists face many of these prejudices, and while getting that kind of a review is upsetting, I chose not to focus on it. I preferred to take a different direction, away from victimization. For example, my portrait series “Head Shots” allowed men to represent themselves in ways that revealed their vulnerability, which I felt the conventional representation of masculinity denied them. In a way, “Head Shots” felt like a gift to men. It felt empowering to give something rather than focus on myself. It felt good, and that’s where I put myself as much as possible in my work and life.

Aura Rosenberg, “Head Shots” (1991–96), installed at Kunstmuseum Stuttgart. Photo courtesy of the artist.

It seems like even as you move between different mediums and subject matter, you often take ideas from one series and rework them in the next. Does reworking an idea revitalize the process of creating?

Absolutely. I can give you one recent example. I worked on my series “Dialectical Porn Rock” from around 1988 to 1993; then, I moved on to other work. Around five years ago, there was renewed interest in “Dialectical Porn Rock.” I didn’t have much of that work left, so the question was whether I would make more rocks. I wasn’t opposed to that, but I wanted to try something different.

I started to think about the eroticism and violence in Renaissance marble statues, like those of Giambologna or Bernini. I thought, why don’t I photograph those statues instead of using porn pictures and decoupage them on marble instead of rock? Pictures of marble statues on actual marble had an uncanny feeling. The fragmented images of the figures felt like ruins.

I recalled Pygmalion and the age-old desire to bring stone figures to life. It inspired another ongoing series titled “Statues Also Fall In Love.” Here, I’ve shot videos where statues transform into performers who enact a short scenario before becoming petrified again. The series also includes lenticular prints that flip between images of statues and porn actors in similar poses. I try to match the two, so they flip back and forth seamlessly.

Installation view of “Aura Rosenberg: What Is Psychedelic” at Mishkin Gallery. Photo: Isabel Asha Penzlien.

Did that influence your exhibition “The Bull, The Girl + The Siegessäule” at Efremidis Gallery where you showed prints of statues alongside miniature monuments and what looked like bits of rubble?

Yes. It’s funny how ruins have come into my work in different ways. After working with classical marble figures, I became interested in the wildly popular Bull and Girl statues in New York’s Financial District. My work often involves a dialectic between high and low. Laura López Paniagua discusses this in “Passions Set in Stone,” an essay she wrote for What is Psychedelic, a book published in conjunction with my upcoming exhibition. Laura describes it as a debate between Apollonian classicism and Dionysian debauchery.

The Charging Bull and the Fearless Girl are both unauthorized statues. Arturo Di Modica placed the bull secretly in front of the New York Stock Exchange in the late ’80s to celebrate the entrepreneurial spirit of Wall Street. Later, the city moved it to Bowling Green. After this, an advertising agency commissioned Kristen Visbal to make the Fearless Girl. On March 7, 2017, they installed it facing off the bull—one day before International Women’s Day. Di Modica went crazy. He felt that this subverted the meaning of his statue, but people loved it. When I tried to film or photograph the two, tourists were always hanging all over them. Did you ever see them together at Bowling Green?

Not in person, but I saw photos and read all of the discourse, which I thought was interesting. Like you were saying, statues are everywhere. Lately, people are starting to pay more attention to them and even challenge them. Why do we still have statues in the South of politicians who were former slave owners? It feels like this reckoning with statues is everywhere right now.

It is everywhere. Right after the fall of the Berlin Wall, authorities tore down statues of communist leaders. Statues mean a lot to us. They embody our desires. That’s why we want to surround ourselves with them. I wasn’t interested in the Bull and Girl statues as emblems of capitalism. Rather, the charged space between them that people were caught in, almost unaware, intrigued me. It was a psychosexual space connected to ancient mythologies like the Minotaur. Picasso, for example, identified with the Minotaur during his relationship with the young Maria Therese. So, there were many different layers that I wanted to play around with.

When Tenzing Barshee suggested a show of this work at Efremidis in Berlin, I added another element. I’ve lived between New York and Berlin for 30 years and wanted to bring some of my personal history into the show. My father fled Germany during the war and lost his citizenship, but later I claimed mine. So I proposed to Tenzing that we include the souvenir I made of The Victory Column (Die Siegessäule), a well-known Berlin monument. I made this souvenir as part of Berlin Childhood because Walter Benjamin wrote about it in his memoir.

Installation view of “Aura Rosenberg: What Is Psychedelic” at Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica, courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

I was thinking at first how this series was referencing your earlier sculptural works because of the rocks on the floor. I didn’t even realize there was a connection to your Walter Benjamin work as well. Can you explain that connection?

Berlin Childhood starts with the sentence: “O brown-baked victory column with winter sugar from the days of childhood.” I first assumed that this was a gingerbread Victory Column his mother made for him—and only realized later that it was a metaphor. So I decided to bake a Victory Column sculpture for my show at the Daadgalerie in Berlin in 2001.

I searched for a souvenir of the Victory Column to give the baker as a model but couldn’t find one anywhere. I wondered why there were no souvenirs because it’s such a prominent monument. It commemorates German victory in the Franco-Prussian War. I looked into its history, and found that in the ’30s, Hitler and Albert Speer moved it to the middle of the Tiergarten, anticipating the victorious Nazi troops would march past it on their way back from Russia. And “souvenir”—the word means to remember, right? People want to repress the column’s fascist past. Even now, nobody is making Victory Column souvenirs. Efremidis has huge windows; people would stop and look in partly because they were unaccustomed to seeing these souvenirs. I put the Bull, the Girl, and the Victory Column together so we could see their intended meanings in new ways.

This practice of taking apart and putting back together seems to run through your work. As you’re preparing for your upcoming show, what has it been like to think of all of your series together? Are you noticing new connections?

Many of these connections arise in the context of conversations like ours. Telling you about it, I unearth things I hadn’t thought about before. That’s why I told Alaina Claire Feldman, the curator of the shows, that the most important thing for me is to produce a book where writers can discuss this heterogeneous body of work. My work has always consisted of themes that would seem mutually exclusive. I can’t and don’t necessarily want to try to make everything fit together.

Installation view of “Aura Rosenberg: What Is Psychedelic” at Mishkin Gallery. Photo: Isabel Asha Penzlien.

You’ve told the story before of how your porn rock series was born from a joke. You took pages from porn magazines your friend, the artist Mike Ballou, used in his sculptures, pasted them on rocks, and hid them in the river in hopes he would see them and think he was hallucinating. This comes to mind when I think of the title of your survey, “What Is Psychedelic.” Is this a question that you have asked yourself throughout your career? Or a statement directed to the audience?

That never occurred to me! “What Is Psychedelic” is a question both for me and the audience. As a young artist, I met my first husband, David Hatchett, in the Whitney Independent Study Program. We were both interested in the formal ideas of modernism that sought to define painting in terms of its inherent properties. But purification for its own sake seemed too patriarchal.

That’s what led me to make my image-text paintings What Is Psychedelic and Spaced. I was trying to conflate the message and the experience of the paintings. I wanted painting to be a psychedelic experience. I wanted to invoke a purely optical experience free from all of the constraints modernism championed. For a very long time, I’ve worked with those ideas because I find freedom in constraints. I like to have something to hit up against. Rather than rejecting limitations, I look for ways to bring them into my work that both uphold and overturn them.