Art World

‘He Could See the 21st Century Coming:’ Why Georges Perec Is the Art World’s New Favorite Author (Again)

Forty years later, curators are taking note of the late author's prophetic writing about globalization, destabilization, and identity.

Forty years later, curators are taking note of the late author's prophetic writing about globalization, destabilization, and identity.

Hili Perlson

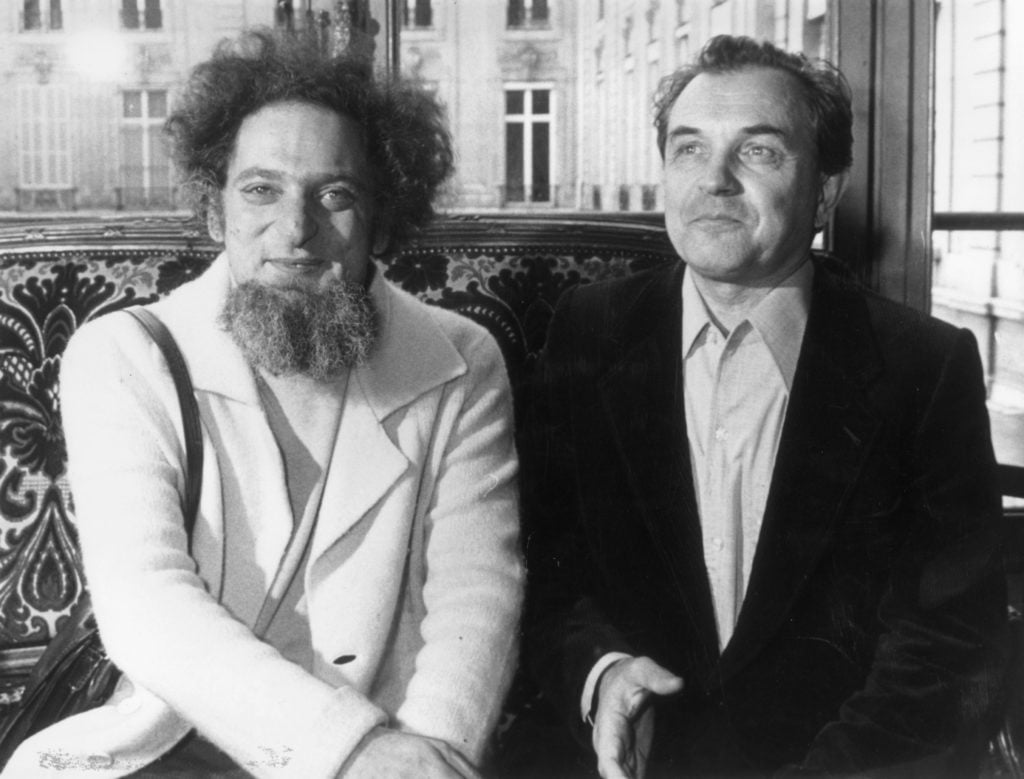

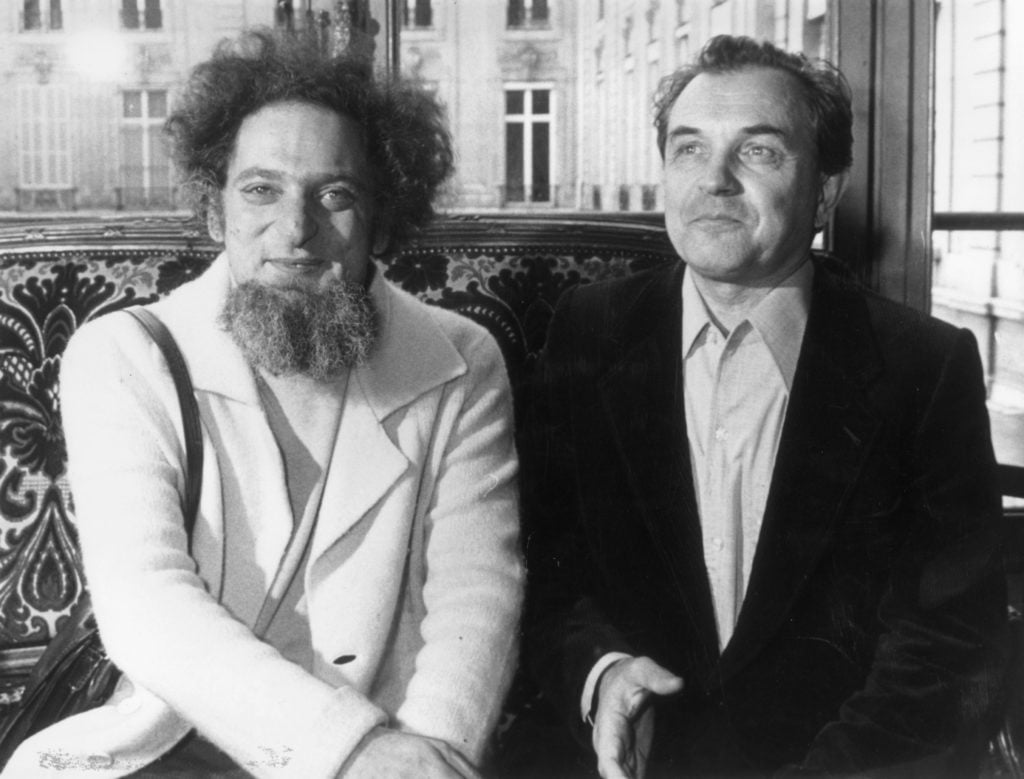

The French novelist, filmmaker, and essayist Georges Perec passed away in 1982, at the age of 45. His novels, however—regarded by many in the literary world as classics on par with Proust, Kafka, and Nabokov—have never ceased occupying the minds of artists and curators in the decades since. This year, almost four decades after the publication of his best-known novel, Life A User’s Manual, the curators of two international biennials—the 15th Istanbul Biennial and Art Encounters, Romania—are citing the writer’s work as a key influence.

So what makes Perec—whose recurrent themes of absence, loss, memory, and transmuting spaces connect to his own troubled biography—resonate so strongly in the art world today?

Perec’s masterful books are characterized by linguistic trickery and self-imposed constrictions, his most audacious being the 1964 novel La disparition (translated in 1994 as A Void), which runs for about 300 pages without ever using an “e”—the most common letter in the French language. (Last year, to mark Perec’s 80th birthday, Google France’s homepage dropped the “e” from the company’s logo.)

Perec was affiliated with a coterie of writers and mathematicians who formed the group OULIPO, inventing axioms as directives for experimentation with word games. But his work, albeit linguistically titillating, is often tinged with melancholy. Born in mid-1930s Paris to Polish-Jewish immigrants, Perec lost both his parents at a young age. His father died as a soldier in World War II, and his mother was later deported by the Nazis, and is assumed to have perished in Auschwitz around 1943. His semi-autobiographical W, or the Memory of Childhood (1975) charts the blurry uncertainty of his memories of his parents.

Erkan Ozgen, Wonderland (2016) at the 15th Istanbul Biennale, presented with the support of SAHA – Supporting Contemporary Art from Turkey. Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren, courtesy of the artist.

In their impassioned catalogue essay for this year’s Istanbul Biennial, the artist-curators Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset describe how Perec’s 1972 novella Species of Spaces shaped their thinking about the (subtly political) exhibition, titled “a good neighbor.” “Perec encourages an unconventional way of looking at what may seem very familiar—be it the space of the home or the world surrounding us,” Elmgreen and Dragset told artnet News via email.

Meanwhile, the biennial Art Encounters, taking place across various venues in Timișoara, Romania, this month, borrowed the title of its 2017 iteration from Perec’s most celebrated tome, Life A User’s Manual (which is, despite its title, hardly something you’ll find in bookstores’ self-help section). Interestingly, the biennial’s curators Ami Barak and Diana Marincu also chose to focus on Romania’s connections with its geographic neighbors. Featuring works by artists including Anri Sala, Dora Budor, Camille Henrot, Julius Koller, and Mary Reid Kelley, Art Encounters looks at works that “survey and compile fragments from everyday life,” a description that is easily applied to, if not created in direct reference to, Perec’s modus operandi.

“Perec wanted to be a painter when he was young but quickly realized he had no talent for it,” David Bellos, professor of comparative literature at Princeton and Perec’s biographer, told artnet News when asked about the writer’s connections to art. “On the other hand, the visual dimension of Perec’s writing is clear,” he says, citing Perec’s first novel Les Choses (Things: A Story of the Sixties) and Life A User’s Manual—both translated by Bellos in 1990 and 1987, respectively.

Life weaves together a plethora of stories, told from alternating perspectives, about the residents of a Parisian apartment block. Only at the very end does it become apparent that the complex prism actually describes a large-scale painting that the central character—tellingly named after a pseudonym Perec himself had used—has failed to complete. “In that sense, the novel is a kind of revenge for Perec’s own failure as a painter,” Bellos says. “It shows he can do in writing what a painter could not.”

“Had he not died so suddenly in 1982 he would most likely have become increasingly involved with the art world.”

View of “Life a User’s Manual” (venue: Timco Hall). Flaka Haliti’s sculptures, individually titled Sochima, Edgar, Daniel, Tshego, Nihal, Oyane, Ms. Dagrou, Anna, Abigail, and Quentin (2015). Photo by Ovidiu Micşa, courtesy of Art Encounters.

Could it be purely coincidental that two curatorial duos working on two different biennials chose, in 2017, to take inspiration from the same writer? Is there an element to his work—which is no light fare—that makes it particularly suited to respond to our current, unstable times?

Elmgreen and Dragset note that in Species of Spaces, Perec prompts the reader—by changing perspectives from one’s bed to the street, out of the city, and into the world—to reflect on what it means to coexist with strangers in shared spaces. This is echoed in the Istanbul Biennial, the curators say, as participating artists create links and parallels between their intimate, personal experiences and larger societal issues. Perec’s style, often shaped by arbitrary constraints, “renders the known unknown,” they add. “By rendering even the most familiar unstable, Perec becomes an advocate for being less afraid of the unfamiliar, a concept we also want to convey through the works exhibited in the biennial.”

In a political climate that is witnessing the advent of nationalism across the world, and the melting away of standards once believed to be pillars of democratic societies—accountability, truth, the right to dignity—destabilization and insecurity are on the rise. “[M]any of the biennial’s works show a great sensitivity towards people’s realities being in constant flux, and towards the human capacity for dealing with unknown circumstances,” Elmgreen and Dragset say.

Similarly, the curators of Art Encounters attempted to show how artists react to the unsettling complexities they confront. “The context [of the novel Life] offered us the possibility to trace a large array of ideas which allow themselves to be discovered gradually,” they say.

Alin Bozbiciu, Ritual, (2017). Photo by YAP studio, courtesy of Alin Bozbiciu and the photographer.

Several works in the Istanbul Biennial also relate to memory and absence, particularly Mahmoud Khaled’s site-specific installation Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man. The work is a museum honoring a fictional Egyptian homosexual man, dealing, as the curators describe, “with traces and forms of memory and how to morph these into narrative and shared spaces.” Sadly, the piece is becoming even more relevant, as Egyptian authorities recently prosecuted dozens of homosexuals on draconian charges.

There’s a recurring theme in Perec’s work, evident in both biennials as well, of the possibility of different, parallel life paths. “Perec’s adult life was lived within the confines of the Latin Quarter of Paris but he was always aware that he could have been someone else,” Bellos says. “As he says in [the novel] Ellis Island and the People of America, it was only by chance that he was not Canadian or Argentinian or Israeli or American, as were many of his more or less distant relatives.” It is perhaps this unique non-reliance on, or rejection of, national identities that resonates so strongly with the curators of both exhibitions. “Perec is a wonderful paradox of an entirely French writer who felt he was not essentially anything at all in national or cultural terms,” says Bellos. “He was at home in words and in books, as he explains in W, or The Memory of Childhood, but not anywhere else.”

“His ability to incorporate minute detail alongside anecdotal sprawl always makes his work so captivating and thought-provoking to read,” say Elmgreen and Dragset, adding that “this push-and-pull between rules, structures, and categorization on the one hand and disobedience, freedom, and multiple identities on the other might be something that resonates particularly well with today’s society though, not least the art world.”

Mahmoud Khaled, Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017).

Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren, courtesy of the artist.

“Like Perec, we are interested in the way that spaces direct our behavior and influence our lives,” say Elmgreen and Dragset. “Also, we like how Perec is not afraid of the banal. We have to acknowledge the banality of life before we can move beyond it.”

“Perec is a fabulous writer,” Barak and Marincu add, “he grasps, enumerates, describes, exhausts everything that refers to the subject and this, per a methodical construction. [His work] both changes and structures the life and the approach of a curator—ours in any case.”

For Bellos, there is yet another aspect to Perec’s observations that makes reading him today feel strangely prophetic. It has to do with his “unrootedness,” which Bellos says “derives in part from his background as a child survivor of the Holocaust. But I think it derives also and perhaps equally from his sensitivity to the globalizing trend of his own time. Life A User’s Manual is among other things a world tour, touching as if on purpose on every continent and on a very large number of different cultures. It’s as if Perec could see the 21st century coming.”

The Istanbul Biennial, “a good neighbor”, is on view through November 12.

Art Encounters Romania is on view through November 5.