People

At 31, the Painter Avery Singer Is a Bona Fide Art Star. She’s Trying Very Hard Not to Let That Get in Her Way

Singer is included in this year's Venice Biennale—the latest in a steady stream of major institutional shows for the young artist.

Singer is included in this year's Venice Biennale—the latest in a steady stream of major institutional shows for the young artist.

Taylor Dafoe

In 2011, Avery Singer was an artist without an art form. She was sitting in an empty studio, hard up for money, wondering what to make. Fast forward eight years later, and she is one of the most successful young artists of her generation—a painter, equally popular with collectors and curators, who merges an innovative high-tech process with classical painting tropes.

In an art world desperately asking itself how painting can remain relevant in a hyper-digital age, many have converged on Singer as the answer. At the same time, she has become the art market’s latest golden goose. Last November, one of her paintings sold at Sotheby’s for $735,000, more than six times its high estimate. In 2018, seven of her works ended up at auction, a high number of a young artist who is looking to develop her craft outside the harsh spotlight of speculation.

Her latest work—large paintings she created by rendering images with sophisticated modeling software and then airbrushing them onto canvas with a computer-controlled printer—are now on view in Ralph Rugoff’s Venice Biennale exhibition, her most high-profile outing to date.

“I love painting technique and thinking about what it means to physically paint,” the artist told artnet News on a recent spring afternoon ahead of the Biennale. She was sitting at a messy desk in her studio, a large Brooklyn storefront next to a laundromat. “Those meanings will change over time as we have different politics and different ways of looking at art, and as media continues to expand and explode.”

Singer’s commitment to pushing the definition of painting is exactly what piqued Rugoff’s interest. “Is it digital art, it is analogue art?” Rugoff asked of Singer’s work. “I was looking for things that jam up against the usual cookie-cutter type of thinking.”

For the Biennale, the curator selected seven recent works from Singer, half of which are rendered in the gridded, geometric style that has become her signature. They are based on illustrations originally done in SketchUp, a free 3D modeling software used by architects, designers, and engineers.

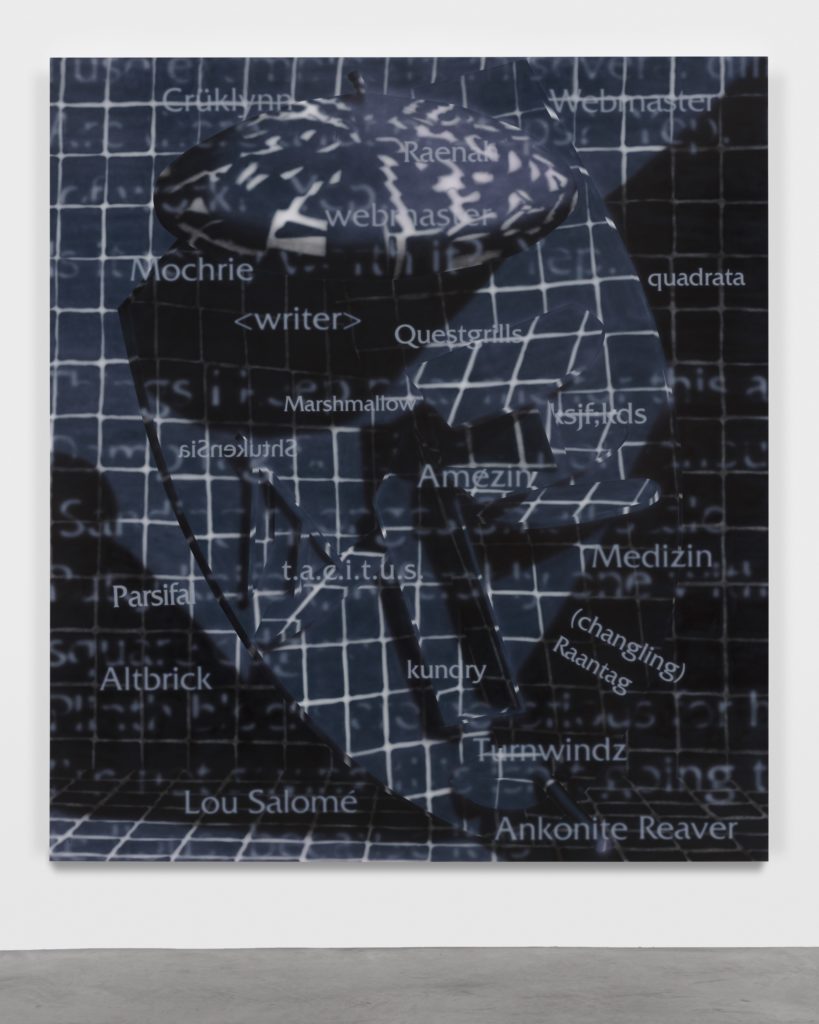

The second batch of works represent a new direction for the artist: Produced with more sophisticated modeling software, her new paintings look like windows onto a video game—a cross between painting, photography, and CGI. In one, Self-portrait (summer 2018), the artist peers through what looks like a fogged shower door. Her finger is outstretched, as if she is either about to draw a doodle on the glass or flip through images on her iPhone.

“I want to make work that explores something that I haven’t seen in painting before,” Singer said. “I guess it’s really a question of being generational—making art that belongs to your generation in some way.”

Singer’s studio used to be a juice bar, and the back room still has all the trappings of its former life—large air vents, the warm corpses of cavernous refrigerators long since unplugged. The manager sits back there, secluded. Singer prefers to work alone. You can catch brief glimpses into her studio from the above-ground train nearby, yellow light filling the window as she works late into the night.

Avery Singer. Courtesy of the artist.

Singer was born in New York in 1987, the daughter of two artists. They lived in a downtown loft, half open-plan apartment, half art studio. As a kid, she recalls her mom blasting music and dancing around while she painted; her dad was more solitary, like Singer is now.

“I’m lucky—I have this example because my parents were artists,” she says. “They lived in a rent-controlled loft for $500 a month, worked as film projectionists, got health insurance through it, and made art. This was my model for life.”

Growing up, she experimented with a number of media—photography, film, drawing—but painting wasn’t one of them. “I grew up with my parents being painters and it seemed like everyone in my neighborhood downtown was a painter,” she said. While she always felt she would become an artist, “I never in my life thought I’d be a painter.”

Avery Singer, Untited (2019). Courtesy of Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler.

She attended Cooper Union, where she dabbled in video and performance but spent most of her time in the wood shop teaching herself carpentry, bronze casting, and welding. After graduation, she worked at a bar on the Lower East Side and secured a studio share in the Bronx. But she was fretting more than she was making art. “I was just wondering, ‘Okay, what do I want to make now that I’m here?’” she said. “I just had leftover materials and no money.”

She made some pencil drawings on an old pad of paper she’d had since high school, but didn’t think they were interesting enough, so she decided to spray them with an airbrush. Around the same time, she was making her first illustrations in SketchUp. Before long, she fused these elements, rendering the digital illustrations with the airbrush. For the first time, she recalls thinking, she might be developing a body of work.

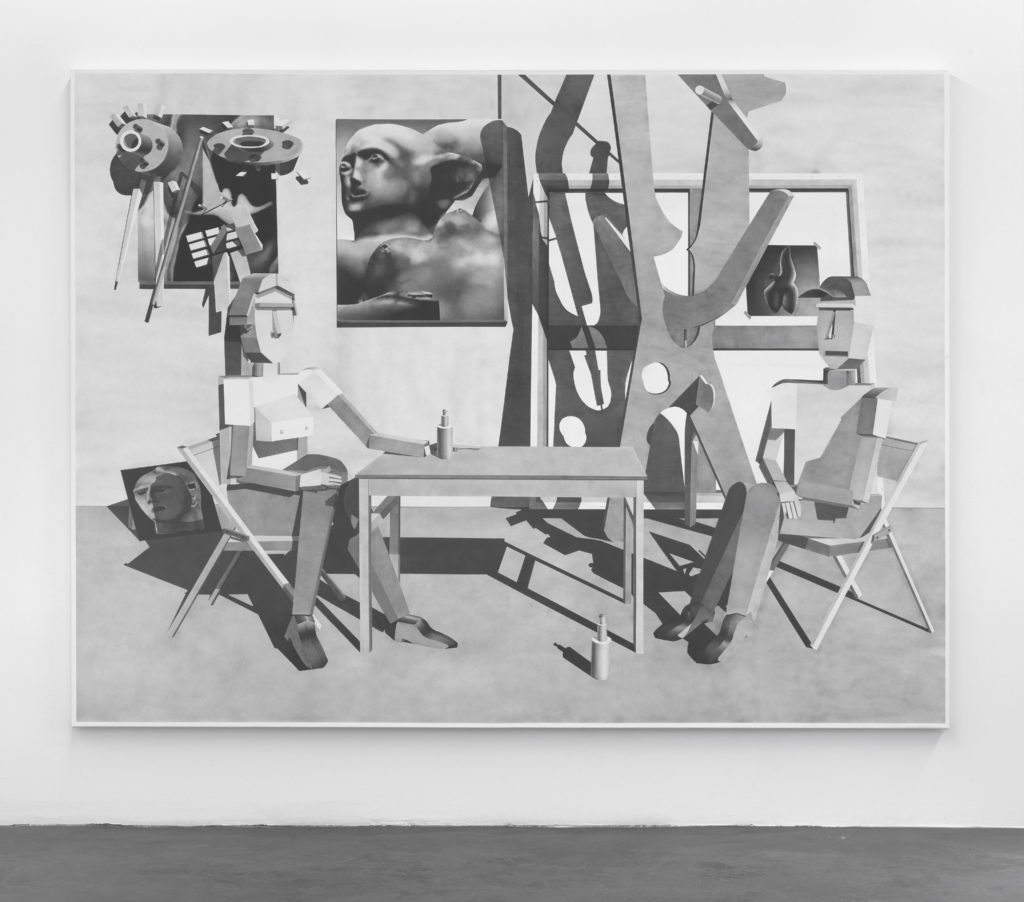

Avery Singer, The Studio Visit (2012). Courtesy of Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler.

As the child of two artists, it’s perhaps not surprising that Singer was drawn to depicting art-world rituals in her work, from life drawing classes to studio visits. (She made her first painting of a studio visit before she’d ever had a real studio visit to speak of.) Charmed by the work, a friend showed it to his dealer, Amadeo Kraupa-Tuskany of the Berlin-based gallery Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler.

Before long, Singer’s imaginary encounter became a reality—and it went off without a hitch. “She was so mature and thoughtful and intelligent, and very aware of the conventions of this studio visit—even though I think it was the first one she’d ever had,” Kraupa-Tuskany told artnet News. “Avery made all these very brilliant moves. She broke the ice by giving us these press releases to read that had nothing to do with her work; she would do them as a writing exercise. I was blown away by how current her work and process was.”

Avery Singer, Performance Artists (2012). Courtesy of Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler.

Singer had her first show at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler in 2013 during Berlin’s Gallery Weekend, one of the best-attended events on Europe’s art calendar. All five works in the show sold, and during opening weekend, Singer received offers for solo exhibitions from three major European institutions.

“Some curators came back twice,” Kraupa-Tuskany recalled. “That was really what impressed me—the show of a young painter having such an impact on a curator.”

Singer remembers getting a call from Amadeo after leaving the gallery one afternoon. “He said, ‘Oh, Avery, you have to stay because Beatrix Ruf is coming to see the show now,'” she said. “And I was like, ‘I don’t know who that is.’” The decorated curator, known for her ability to spot young talent, ended up organizing a solo exhibition of Singer’s work at Kunsthalle Zürich in 2014.

Looking back, Singer refers to that gallery exhibition as the “most impactful thing for me and my career to this point.” It’s led to a steady stream of increasingly high-profile institutional shows, including solo outings at the Stedelijk Museum in the Netherlands and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. She was included in the 2015 New Museum Triennial and the 13th Biennale de Lyon (also curated by Rugoff). She joined the elite gallery Gavin Brown’s enterprise in 2016.

Avery Singer’s work at the main pavilion of Giardini at the 58th International Art Biennale on May 07, 2019 in Venice, Italy. Photo: Simone Padovani/Awakening/Getty Images.

Singer is the rare young artist who attracts institutional interest and market interest in nearly equal measure. But the former can be dangerous; curators often shift their focus if they feel an artist’s work has become too commercialized, and collectors are tempted to cash in, flooding the market and causing a young artist’s prices to crater before they’ve even found their footing.

All eight of Singer’s paintings to hit the auction block to date have sold for more than their estimates—sometimes as many as six times more. While her dealers try to avoid speculation by selling only to museums or collectors they trust not to flip, this dynamic can constrict supply even further, driving up prices more. Art advisor Lisa Schiff admits that Singer’s market has been subject to “some intentional manipulation,” leading some of her work to sell for more than $1 million on the private secondary market.

But the advisor isn’t too concerned. “She’s going to be fine,” Schiff said. “When it’s dangerous is when it happens to an artist of non-quality, because then it’s really just a wave to ride and then buyers just want to get out as fast as they can. But Avery is an artist of quality and has always been very savvy. She’s a real New Yorker and a tough cookie. Her market will go up and down—it happens to everyone—but I think she’ll persevere through it. She gets it, and I’m sure she has a plan.”

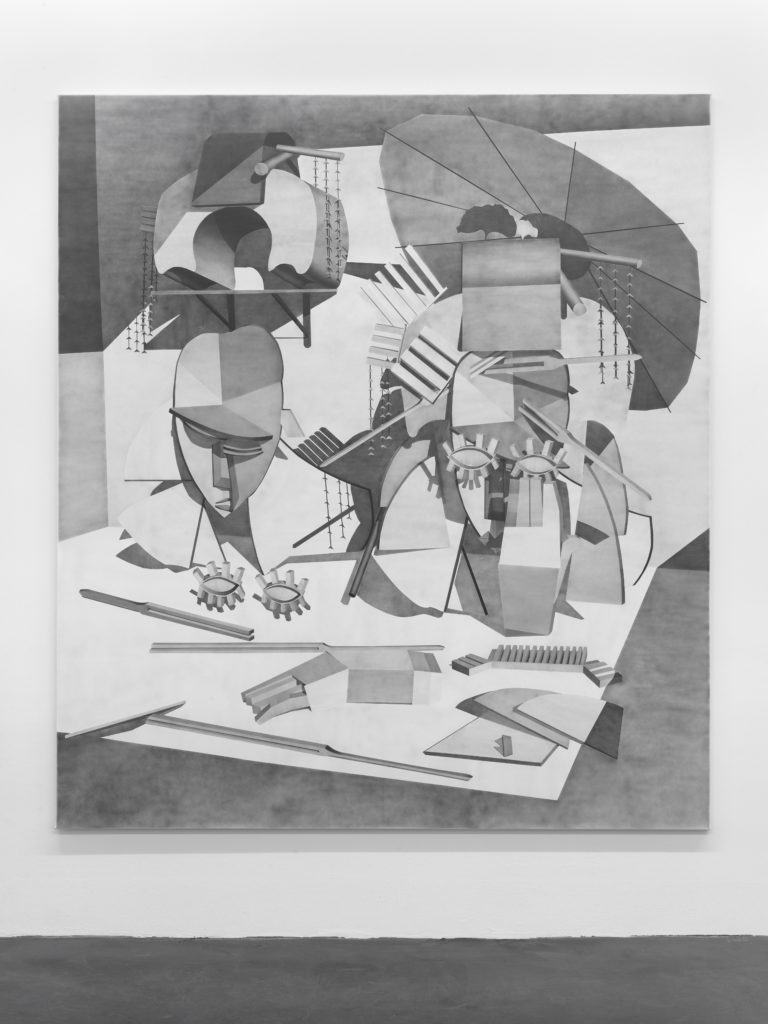

Avery Singer, The Great Muses (2012). Courtesy of Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler.

Singer may indeed have a plan—but that doesn’t mean she wants to talk about it. She says the “art market is essentially insider trading” and that there is a “complete imbalance of power” between collectors and artists. To cope, she’s all but refused to discuss the market for her work publicly; privately, she’s adopted a zen attitude.

“Because you can’t predict it, you can’t plan for it,” she said. “Maybe the best thing you can do is just accept that you’re going to have a moment where people will care more, people will care less.”

Given the amount of success she has found so early in her career, it would be tempting to make the same style of black-and-white geometric paintings for years to come—and make a lot of money doing it. But Singer says she has already left that behind.

“If you give up on yourself and you become lazy and you decide, ‘Hey, this style works for me, it sells, it gets attention, I’m done’—that’s not the way to think about it,” she said. “Once you become lazy with your own work, I think it’s sort of over. I didn’t become an artist to become bored with myself.”