Art & Exhibitions

‘I’m Not Giving People What They’re Used To:’ Awol Erizku on the Challenges Inherent in Remixing His Own Work

The artist's wide-ranging practice refuses easy categorization.

The artist's wide-ranging practice refuses easy categorization.

Naomi Rea

For his latest exhibition, Awol Erizku has transformed the white cube at Ben Brown Fine Arts into a Black space.

Even if you think the artist’s decision to literally paint the walls black is a bit on the nose, the actual content of the exhibition is certainly less heavy-handed than his last outing with the gallery in 2017, which included a graffiti-laden door emblazoned with Trump’s name and a swastika. In “Cosmic Drill,” on view through April 6, Erizku revisits many of the same issues evoked in that earlier show, albeit with a little more trust in the viewer to do the work of unpacking them.

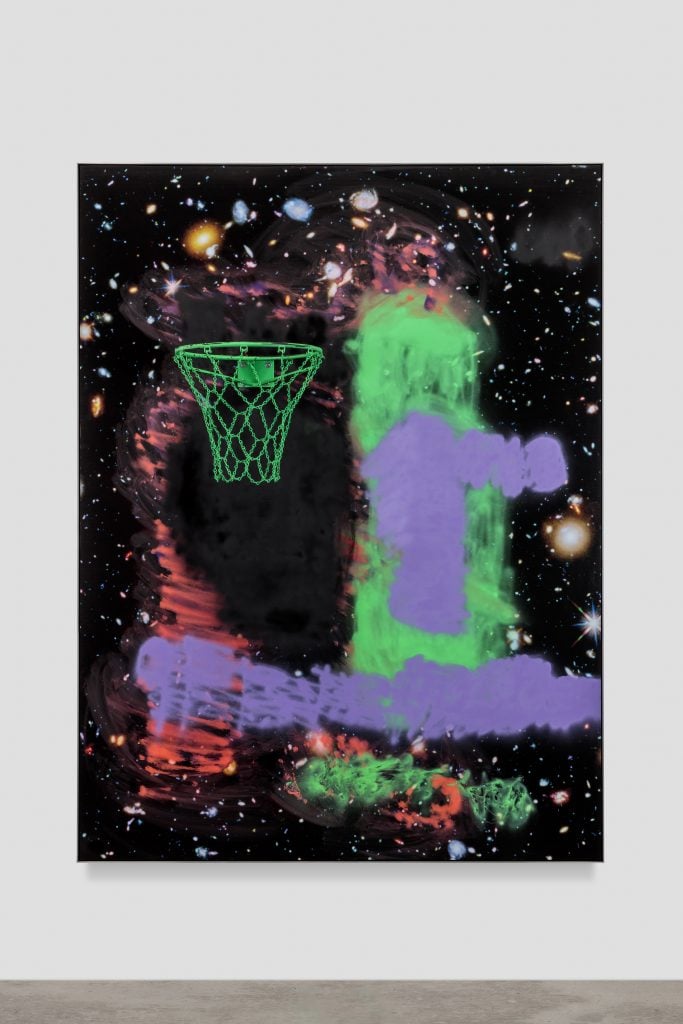

Anchoring the exhibition is a series of artworks that merge photography, painting, and sculpture. On first viewing they’re cool-looking backboards for a series of colorful basketball hoops. Photographs of space, sourced from NASA and printed on aluminium panels, are overlaid with hand-painted patches of buffed-out graffiti markings.

A large-scale marble sculpture of three stacked dice in the colors of the pan-African flag, titled Head Crack [Stack or Starve], monumentalizes cee-lo, a popular dice game often played in inner city parks, including those in the South Bronx, where the Ethiopian-American artist was raised. Erizku has also produced a conceptual mix-tape to score the exhibition, featuring drill music—a subgenre of nihilism-imbued hiphop reminiscent of trap but slower (and, if you can imagine it, more blunt).

Installation view, “Awol Erizku: Cosmic Drill” at Ben Brown Fine Arts London, 2023. ©Ben Brown Fine Arts. Photo by Tom Carter.

In the seven-odd years since he was buffeted to fame after shooting a pregnant Beyoncé, the Los Angeles-based artist’s practice has matured. He has distinguished himself as a multidisciplinary artist while maintaining his profile as an important name in photography. In 2021, he photographed poet laureate Amanda Gorman for Time magazine’s “Black Renaissance” issue, even as he himself is also considered part of that renaissance, a generation of ascendant Black artists gaining recognition across the cultural landscape. His art world bona-fides have continued to sprout. Last March, Antwaun Sargent curated an Erizku solo exhibition at Gagosian in New York and, in September, the artist gained representation in the city from Sean Kelly.

The works on view at Ben Brown were made in Erizku’s L.A. studio, where he decamped from New York four years ago, finding the less entrenched art scene to be more conducive to the kind of slippery work he was making. “It felt like a lawless place. I think there’s a kind of freedom there that I didn’t experience or feel in New York,” Erizku told me when I visited him at the gallery. “I felt like because of New York’s rich institutions that uphold a lot of the formal and traditional values of painting, sculpture, and other mediums, you kind of have to conform and bend to those norms.”

In this latest body of work, Erizku has revisited his older works but instead of repeating his most popular series such as the “Reclining Venus” or “Hand and Rose” works for which he is well known, he has sampled and re-mixed lesser-appreciated work from his archive, folding in new layers.

Earlier versions of the basketball hoop sculptures were shown in 2017, executed on plywood and adorned with Black Panther Party motifs and African masks. “I think this time the direct diasporic signifiers are stripped as a way to get to a more universal kind of reading,” Erizku told me about these more subtle manifestations.

He has dubbed this process retroactive continuity. He doesn’t mind how it is interpreted, either. “The challenge is that now I’m not giving people what they’re used to,” he said. “But for me, it’s far more rewarding to fail in a big way and learn from that as opposed to succeeding in some small fashion, and then being stuck to being that person who only does X, Y, and Z.”

Awol Erizku, Kyrie’s Lament (Shawny BinLaden Type Beat) (2022). Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts.

Trying to encapsulate in explicit terms what Erizku is doing would limit the work on view at Ben Brown, which exists somewhere between the hard edges of pre-ordained categories, like the buffed-out street markings that have inspired it. Erizku sees these as representing a “beautiful and poetic” tug-of-war between the mark maker and the eraser—as both vie for control of the narrative, neither succeeds totally in their aim. “In that erasure process, this other thing sort of emerges and that’s what I’m after,” said the artist.

That “other thing” has been described in critical discourses surrounding Black artistic production in different ways: in a public conversation Erizku had with visionary curator Ekow Eshun and poet Caleb Femi, they evoked what Toni Morrison referred to as “Black liquidity,” a fugitive entanglement of art forms that can take on an improvisational quality.

The layered titles of Erizku’s work also resist straightforward readings. Instead, they raise even more cosmic knots. For instance, Kyrie’s Lament (Shawny BinLaden Type Beat) references the competing narratives engulfing NBA star Kyrie Irving after he platformed an anti-semitic documentary film on social media.

Erizku himself said that his work is trying to touch upon “the Black imaginary,” making references to his own self-expression as well as the art of David Hammons, or the explosive beats of Shawny BinLadin.

“I’m just expressing things I have seen and felt. And I can only speak for myself, so it’s not some sort of collective trauma, it’s none of that,” he said. “This is just all very internal and very personal, really.”

Speaking of his relationship to drill, the violent subject matter of which has become a target of politicians, Erizku said he considers himself a sort of visual “griot”—keepers of oral history in parts of West Africa—who hopes to help preserve the music as an art form by giving it a visual component. “I think there’s rich history in it. I’ve followed it since I can remember, and I see where it’s going,” he said. “At the end of the day it’s an expression, and it’s Black expression, first and foremost.”

Incorporating references to it in his work is a way of “protecting it and making sure that it’s not looked down upon or it’s not considered low brow, simply because other people don’t understand the depth and the complexity of what’s being said,” he noted.

When it comes to the wider narratives surrounding the “Black renaissance,” and his place within that particular canon of artists, Erizku was ambivalent. “I don’t know where I fit in that because I feel like I’m just getting started. I just finished my first monograph literally last week. Yes, I’ve been making work for close to 12 years now, professionally, but at the same time, it feels like chapter one for me.” In a way, then, it’s no wonder that the exhibition feels somewhat like an unfinished thought.

“Awol Erizku: Cosmic Drill” is on view through April 6 at Ben Brown Fine Arts, London.