They spend more time looking at the museum’s walls than anybody else—and now, for the first time, they’re deciding what art will hang there.

For the Baltimore Museum of Art’s (BMA) newest exhibition, the security guards have taken on curatorial duties. The show, “Guarding the Art,” features 25 pieces from the BMA’s collection—including works by Louise Bourgeois, Grace Hartigan, and Mickalene Thomas—selected by 17 members of the institution’s security team. It opens to the public this Sunday, March 27.

The aim of the show, conceived by BMA board member Amy Elias more than a year ago, is to enliven the museum’s presentation—and invite some new perspectives along the way.

“‘Guarding the Art,’ is more personal than typical museum shows,” Elias said in a statement, since “it gives visitors a unique opportunity to see, listen and learn the personal histories and motivations of guest curators. In this way, the exhibition opens a door for how a visitor might feel about the art, rather than just providing a framework for how to think about the art.”

Alfred Dehodencq, Little Gypsy (c. 1850). Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

To choose the works for the exhibition, the guards began meeting over video chat with members of the museum’s curatorial team last year. They were face with some large tasks: scouring the museum’s collection, narrowing down their selections, writing wall texts and catalogue entries, devising lighting schemes—in short, designing and staging an exhibition from tip to toe. (Each participant was paid for their curatorial work through a grant from the Pearlstone Family Foundation.)

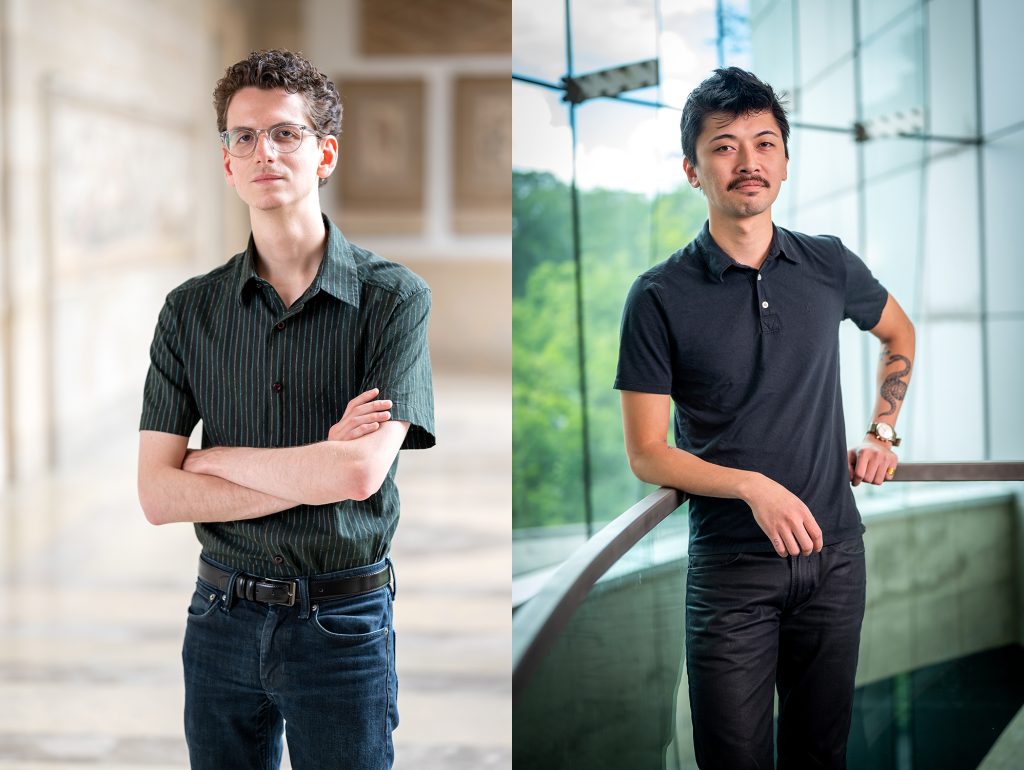

“We were kind of nervous because these are serious folks and this is what they do,” said Dominic Mallari, who has worked at the BMA since 2018. “But it turned out that it was very welcoming and inviting.

For his contributions to the checklist, Mallari selected two artworks: a square, tie-dye-like canvas by Sam Gilliam, and a spare, little-known portrait of a Romani girl by French 19th-century painter Alfred Dehodencq. The latter, he said, stuck out to him among the many ornate paintings in the museum’s Jacobs Gallery of European Art.

“It was the simplest one,” Mallari explained. “You have to use your imagination for it. It was just striking to me.”

Sam Gilliam, Blue Edge (1971). © Sam Gilliam. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Simplicity was the reason that Alex Dicken, another guest curator, found himself drawn to his sole selection, a 1948 blue and yellow landscape by Surrealist Max Ernst. The artwork’s title doubles as a description: Earthquake, Late Afternoon. (Coincidentally, it also looks a lot like the Ukrainian flag.)

“When I think of Max Ernst’s paintings I think of these fantastical creatures and alien landscapes. What interested me about Earthquake, Late Afternoon was that they’re pretty much absent,” said Dicken, a recent philosophy grad from St. John’s College in Annapolis, who began working as a security officer in 2019 and recently switched over to the visitor services team.

“I was interested in the idea that it might have been trying to represent a natural disaster from a non-human perspective, detached from the immediate danger of the situation,” Dicken added. “That came out of investigating it further and thinking about the work.”

Dicken explained that, at the beginning of the process, he and his cohort tried to come up with a cohesive curatorial theme for the exhibition, but nothing stuck. Meetings moved from Zoom to the museum itself, and he even got together with other guards outside of work to tackle the topic. Still the question loomed.

Max Ernst, Earthquake, Late Afternoon (1948).

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

With help from the art historian and curator Dr. Lowery Stokes Sims, who joined the project as a mentor, the group eventually stopped looking for a theme to tie all the curators’ ideas together and instead chose to embrace the multiplicity of perspectives.

“I know someone else started out the same way that I did, investigating the collection for works that had never been displayed before,” Dicken said. “Whereas others had very particular interests—for example wanting to display works from a particular culture or another interest of theirs outside of the museum, another area of study that they are interested in.”

“It really became more about talking about our specific experiences rather than forming a set of themes that would characterize the exhibition,” the guest curator went on. “Over time the focus became, ‘What are the diverse array of selections that various guards will make given their collective time in the galleries?’”

“Guarding the Art” will be on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art, 10 Art Museum Drive, Baltimore, Maryland, March 27–July 10, 2022.