Style

Banks Violette Adds His Hardcore Touch to Celine’s Rock-Influenced Fall Collection

The artist talks about the dark side of Americana and his Hedi Slimane collaboration.

The artist talks about the dark side of Americana and his Hedi Slimane collaboration.

William Van Meter

It’s easy to see why Celine Homme’s fall/winter 2022 outing was dubbed the “glam rock” collection by the fashion press. Titled “Boy Doll,” there was certainly a lot of metallic gleam to catch the eye: silver-fringed capes, lustrous gold trousers, knee-high boots. But the shine obscured the actual theme which was much darker. Celine creative director Hedi Slimane—who has long moved past his signature super-skinny menswear silhouette—actually sent out a fabulously bleak post-punk vision. That vibe is very on-brand for Banks Violette, whom Slimane tapped to collaborate on some of the garments.

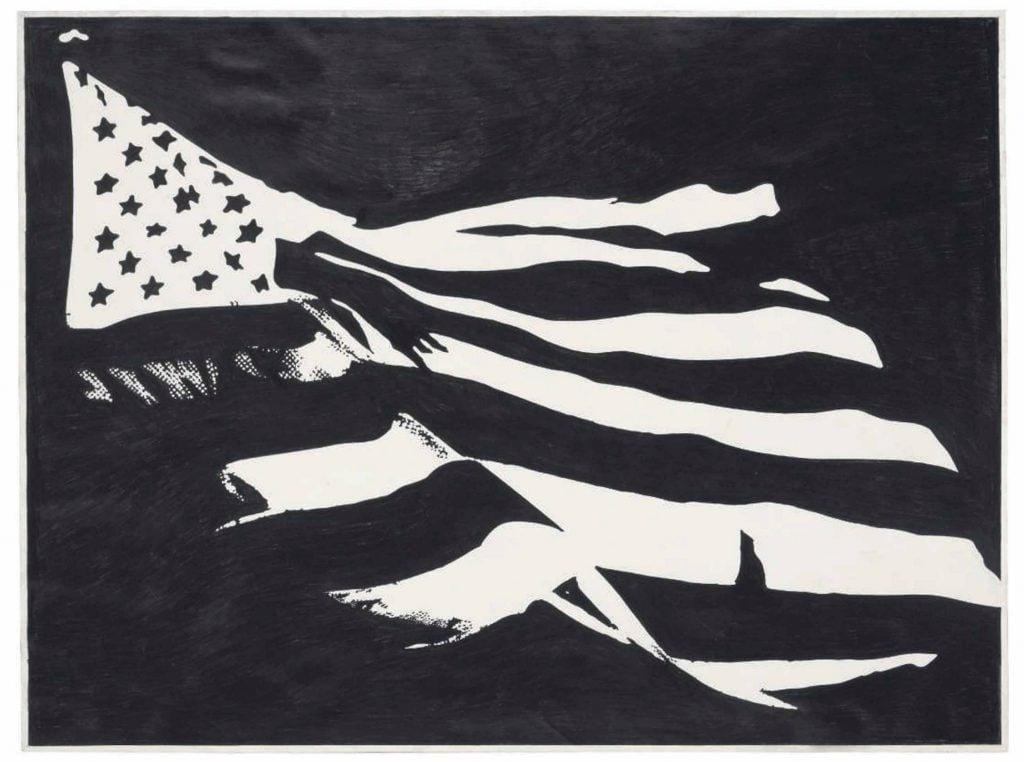

Violette has made a career channeling glam gloom and chic dystopia. The multimedia artist’s tattered, black American flags and ghostly horses adorn select leather jackets, sweaters, and hoodies in the collection (which was released this week online and in Celine stores). Violette wields both subjects with an understanding of the evolving complexity of such traditional American iconography. He sees Slimane as an understanding compatriot.

“He’s legitimately invested with the history of art,” Violette said of Slimane, whom he’s known since 2005. “He and I were communicating a great deal, but in recent years, not at all. Out of nowhere, Celine approached me about doing this.” Violette took a break from working in his upstate New York studio to chat about the Celine collaboration, life, and, of course, death.

How did you narrow down your extensive catalogue for the art that would be used for the Celine project?

Hedi selected a bunch of images, so I had an idea of what sort of visual vocabulary he was interested in using. I just went ahead and made a couple variations of images that I thought he’d be attracted to, that I thought would also work in different media if it was enlarged or embroidered. He gravitated to one sort of set of imagery, which is what I describe as American romanticism. So, I did a couple variations on horses that I thought would just be iconic images. I’ve known Hedi for a while, so I had a pretty good idea of what would and what wouldn’t work.

Banks Violette’s eerie horse adorns a “Boy Doll” leather jacket on the Celine Homme fall/winter 2022 runway. Courtesy of Celine.

A horse and the American flag are the zenith of Americana. But what do these images mean to you?

A lot of the imagery that I’m attracted to is, for lack of a better description, kind of cliché. Something that’s just so overused and kind of stripped bare [of meaning], like a sunset or horses, and you’re like, ‘This can’t possibly be anything but saccharine.’ There’s something about the condition of an image that doesn’t look like it could have the capacity to mean anything.

If imagery is so overused, then the meaning can be diluted. There is a blankness to saturation, and that can be wielded in a purely graphic sense.

Yeah. And there’s something in the way they get reanimated, as a factor for somebody’s belief or faith in something. It doesn’t matter if it’s a romantic ideal or some bullshit notion of patriotism. Usually something ugly happens as a consequence, and I’m super-fascinated by that.

As Yet Untitled (Flag) (2006). Courtesy of Banks Violette and Gladstone Gallery.

As a consequence? Can you be more specific?

Do you know The Sorrows of Young Werther, by Goethe?

Yes, I wrote a paper about that in college. Werther is a drama queen, besotted and forlorn in a state of hysteria.

That kind of prefigures what I grew up with, which was satanic panic—this idea that Dungeons & Dragons is gonna cause you to kill your mom! The idea that artifacts of culture can function as a landmine: that if the wrong person engages with it, fiction can become literal fact. There is something fundamentally fascinating about that. And it doesn’t matter if it’s Goethe or Dungeons & Dragons or some lunatic obsessive relationship with the American flag. They’re all part of the same continuum.

In the last few years for many, the flag has become symbolic of violence. A Jasper Johns flag didn’t have those visceral connotations. But with this Celine collaboration, I see that aspect negated, and it’s being reclaimed in a sense—especially within a glam-tinged collection called “Boy Doll” that questions notions of masculinity. It kind of diffuses the flag.

I’m excited that you picked up on that. I live in upstate New York in a liberal college town, but I’m surrounded by a lot of real ugly shit. I see American flags, and it makes me think of racism, which is a fucked-up way to relate to your national identity. So seeing Hedi use that flag in the way he engineered that collection is great. This gives me some faith that you can sort of jimmy the meaning a little bit sideways.

Or even go back to the original meaning or the positivity within. An American flag is such a charged emblem.

After the past few years, you and I have a very specific response when we see that. Just to see somebody respond to it, I’m imagining with this kind of, like, romantic valance attached to it—wow, that’s refreshing. [Because] I look at that, and I think like you’re a racist lunatic. I forgot that there’s another dimension to our national character that is redemptive.

Once you gave Celine the images, was there back-and-forth developing the garments, or did Hedi Slimane just run with it?

I trust Hedi. I really enjoy what he does. I’m not interjecting what I think the fashion should be. That’s not my job. It would be kind of silly. So, I was just super-fascinated to see what he ended up doing with it. And I’m really pleased with it. The work is cool.

Behind-the-scenes process kind of stuff is a nightmare. It’s cool you could just hand in your art and then see the finished product in a show with shiny boots and music.

I make stuff for a living; I’m not particularly engaged with watching other people do the same thing that I do. I know what that looks like.

Banks Violette’s graphite on paper burnout (fadeaway), vol. 1 (2003). Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The oversized leather jacket is dope. That’s gonna be so cool for you to see someone wearing it on the street.

It is, but I’ve worked with enough bands in the past where I’ve had these random occurrences where I’m sitting next to somebody and they’re wearing a T-shirt that I’ve done.

What’s your history designing band merch?

When I was a teenager, I did a bunch of stuff for hardcore bands, like Earth Crisis and the Victory Records label, and then later I collaborated with musicians for art projects—I did a couple things here and there for Sunn O))) and some other bands. But periodically, I’ll be in the airport and see somebody with this T-shirt and be like, I know that there were only 20 of those things made. Who are you? It’s really weird when those kinds of things happen. Seeing it on a Celine jacket, that’s just gonna be a much different demographic than I’m used to engaging with.

Installation view of the 2007 exhibition “Banks Violette” at Gladstone Gallery. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

I’ve been to the upstate town of Ithaca where you live with your wife and stepchildren; it is a very rural area. But besides the Americana vibe in the Celine collaboration, I don’t really see your surroundings reflected in your work, which doesn’t exactly scream ‘pastoral existence.’ Your installations are more modernist and sleek.

Ithaca’s got this Thomas Mann [Death in Venice] kind of history. If you go, you’ll see that Ithaca is gorgeous. You’ve got an ivy league university [Cornell University] with a bunch of these giant ravines. For a very long time, there was a string of suicides with people falling into this landscape. Robert Smithson—the very first Land Art group show was put on at Cornell. There’s a salt mine here. So all these kinds of things like entropy, decay, social disillusion—that’s upstate New York. The aesthetic manifestation of it, the slickness, those don’t correspond to the landscape. But the logic of it is absolutely informed by the landscape.

When you mentioned the mass of suicides, I immediately pictured the tragic ballet of the David Wojnarowicz buffaloes.

The Mormons are from here. Branch Davidians are from here. It’s this lunatic strain of American millenarianism: the world is gonna end and you’re all gonna die, and Jesus is super pissed at you. That has its origins in this area, this over-investment with faith and a specific species of American credulity. We also have the Cardiff Giant. It was this hoax where this guy convinced everyone he dug up the body of a giant.

O.K., now it really makes sense how things like the occult speak to you when this dark mysticism is interwoven with this wondrous landscape. It sounds like H.P. Lovecraft’s vision of New England. What are you working on now?

The next big project is a museum show, which is kind of functioning as a retrospective, in Belgium [at the Musée d’art de la Province de Hainaut in Charleroi]. There’s potentially gonna be other institutions involved with it. Otherwise, I’ve been working on a bunch of drawings, trying to change how I make them.

It’s just trying to mechanically figure out different ways to produce these things—that’s what I’ve been doing, because I’m older. Projecting something and sort of scrunching over and twisting into weird positions to trace it out, I can’t physically do it. And I’ve been working on a few sculptural maquettes as tests. I’m just trying to make a bunch of different things so I can stare at them and get an idea. Ideally, this fall I’ll have a bunch of things of fabricated.

What are you listening to now?

I’ve been listening to Slaves a lot, which is super goofy. It’s like the history of English punk rock in one band, sort of like if you compress Wire and the Avengers together. It’s really catchy. I try not to listen to my metal stuff in the house, because it definitely scares teenagers.

Banks Violette, Not yet titled (proposal for a burning drum kit) (2007). Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.