Books

87-Year-Old Artist Barbara Kasten on How Her New Career-Defining Monograph Shows She’s More Than Just a Photographer

The book unpacks the multidimensionality of the artist's practice.

The book unpacks the multidimensionality of the artist's practice.

Taylor Dafoe

Barbara Kasten’s best-known work is, in a sense, all about flattening. So good is she at this technique, though, that her successes have had a flattening effect on how her work has been received, understood, and supported.

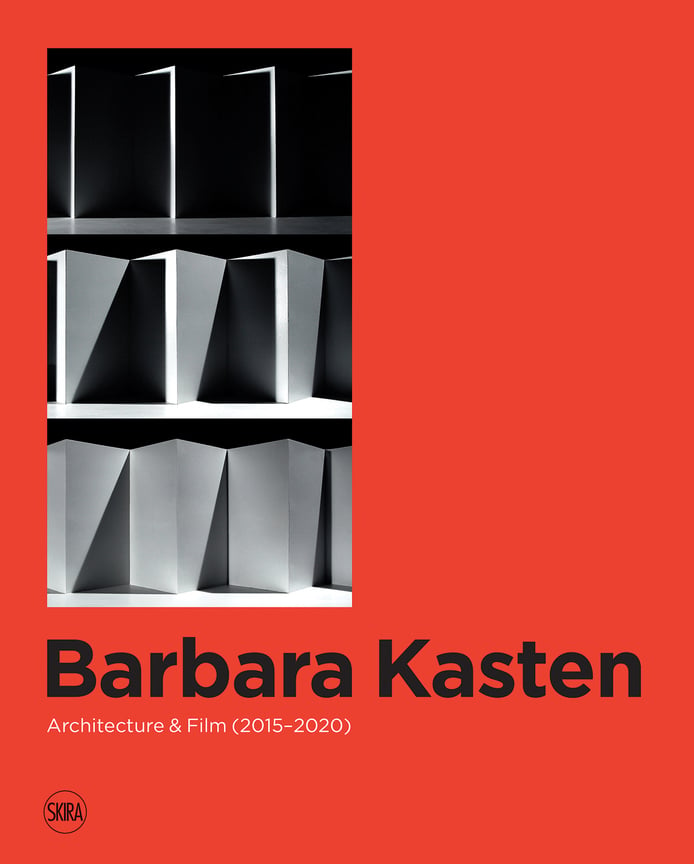

Fortunately, a new monograph from Skira looks to expand the narrative around the now 87-year-old artist. Called “Barbara Kasten: Architecture & Film (2015–2020),” the book looks at the most recent chapter of her five-decade-long career—an ultra-fruitful period for the artist that coincided with a newfound interest in her work from a young generation of curators and critics—outside the limiting lens of photography.

“Barbara Kasten: Architecture & Film (2015–2020),” 2023, published by Skira.

If you’ve ever read an article or review about Kasten, chances are it contained a line like this: “In her studio, Kasten stages makeshift tableaus with angular pieces of plexiglass, mirror, and other industrial objects, then lights and photographs them.”

You probably also learned about the illusive quality of her pictures and their supposed debt to the geometric abstractions of the Constructivists, say, or the material preoccupations of the Light and Space movement. You almost certainly read that she prefers old-school, analog processes, and never uses Photoshop.

This information is all accurate. It’s even useful, offering readers ingress into the artist’s reference-laden world. But you’ll notice that in the passages above, as with almost every piece of writing about Kasten, the descriptions of the artist’s work are actually just descriptions of her process, and they’re recounted largely through the language of the photographic. That hasn’t always sat well with her.

“The reality is that I never thought about myself as a photographer,” Kasten said in an interview over video chat. She was in London at the time, prepping for her new show at Thomas Dane Gallery, and wearing a pair of effortlessly chic, pistachio-colored glasses.

Photography, she went on, is “sort of circumstantial to what I do. The core of what I do is really sculpture—sculpture that incorporates the use of space and color and light and form. All of those things are more important to me than the production of a photograph that ends up being the object that you see.”

But, Kasten conceded, “sometimes you get identified one way and people have a hard time letting go of it.”

Barbara Kasten, Collision 5E (2016). Courtesy the artist and Bortolami Gallery, New York.

Indeed, much of the criticism around Kasten tends to focus on how her work exploits the flattening and compression effects of the camera to turn three-dimensional scenes into two-dimensional objects that play with perspective. And that makes sense. One of the joys in looking at a Kasten photograph is figuring out how they were made—and the artist, to her credit, often gives viewers just enough clues to solve the puzzle: Even as scale is distorted and perspective muddled, the materials are recognizable, as is the setting in which they were arranged and documented.

But with so much attention paid to her ability to turn photographic properties in on themselves, her work has historically been portrayed as though it was fundamentally about photography. Kasten is painted as a kind of dogmatic formalist who erects temporary installations just to take a picture of them. The installations themselves, and the work that went into them, are subordinate to the final picture.

If this is the only aperture through which you think about Kasten, then her work will merely serve to reaffirm what we already know about photographic images—that they can be manipulated in the name of aesthetics or politics, that they lie. Such a single-minded approach lowers the ceiling of her creations. It also decenters the artist’s own role—and her body—in our understanding of her work.

This, Kasten said, is a masculine approach to thinking about photography that has been baked into the medium since its creation. “It was a mechanical, technical achievement rather than an artistic one that brought photography into our lives,” she said.

Barbara Kasten, Scenario (2015). Photo: RCH | EKH. Courtesy of the artist.

The limitations of the labels foisted on Kasten were apparent to curator Stephanie Cristello, who edited the Skira book. “When we started having these conversations,” Cristello said of her preparatory meetings with Kasten, “she was pretty vocal about a dissatisfaction of being lumped into a medium.”

For the curator, Kasten’s ephemeral, in-studio installations—not the photographs of them—are at the core of the artist’s practice.

“The camera figured into her work only insofar as it could document what was there before she had to take it down,” Cristello explained, adding that the book was borne from a question that doubled as a challenge: “How can we… provide a different perspective to where the photographs came from?” The book, she said, “is almost like a different origin story, but through the conversation of new work.”

With the monograph, Cristello posits new ways of situating Kasten’s work, drawing connections to architecture, theater, choreography, and film. “I was trying to situate it as a phenomenological project—that is, a conceptual abstraction project,” she said. “Sometimes there are photos, sometimes there are sculptures, sometimes there are installations, sometimes there’s film. But in the end, it’s all part of the same project.”

The monograph’s many plates document Kasten’s recent creations, including the elaborate plexiglass and metal installation she built for the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe-designed Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology, as well as the sculptural video pieces featured in her 2020 solo show “Scenarios” at the Aspen Art Museum. An essay by Cristello, meanwhile, looks back to some of Kasten’s earlier, lesser-known bodies of work, such as a series of intimate cyanotypes and the stage set she designed for a 1985 collaboration with choreographer Margaret Jenkins.

Barbara Kasten, Artist/City (Crown Hall) (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Bortolami, New York.

These artworks—the old ones and the new—do not easily fit the prescribed, process-obsessed descriptions so often found in writings about Kasten. But they’re certainly not anomalies either. That these non-photographic creations haven’t been seen as much is, for Cristello, a question not of quality, but support.

“I don’t think the way she’s worked has changed,” the curator noted. “I just think the opportunities provided to her at this stage of her career have changed immensely.”

In the interview, Kasten said she’s “enjoying a renaissance” in terms of how her work is being appreciated—and who is doing said-appreciating.

“It’s a younger generation,” she explained, “that has been open to thinking differently and giving credit to other experiences that aren’t so rigid, so conservative. I’ve found an audience that relates to what I do. Age has nothing to do with it. We happen to be in different generations and are still able to speak to one another.”