On View

Barbara Kruger Updates Her Iconic Text-Based Works for the TikTok Era

Reinvented for the internet age, the artist's works reveal the technological leaps—and social setbacks—that have occurred within her lifetime.

Reinvented for the internet age, the artist's works reveal the technological leaps—and social setbacks—that have occurred within her lifetime.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

When a serious museum show dedicated to a crowd-pleasing artist like Yayoi Kusama or Olafur Eliasson is branded “Instagram-friendly,” it is usually meant as a backhanded compliment. Yet “Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You,” a new survey of works by Barbara Kruger at London’s Serpentine South Gallery goes one step further: it is proudly TikTok-friendly.

Since rising to prominence in the 1980s, the legendary American conceptual and collage artist has proven that she’s still well ahead of the curve. Take, for instance, the Serpentine show’s TikTok filter that allows users to make their own versions of one of Kruger’s most iconic artworks, Your Body is a Battleground, with their selfie cameras. This savvy conceit takes an eye-catching graphic that was first mass-reproduced in print in the 1980s and jettisons it across the globe at lightning speed thanks to the power of social media.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (No Comment) (2020). Photo: The Art Institute of Chicago, courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers.

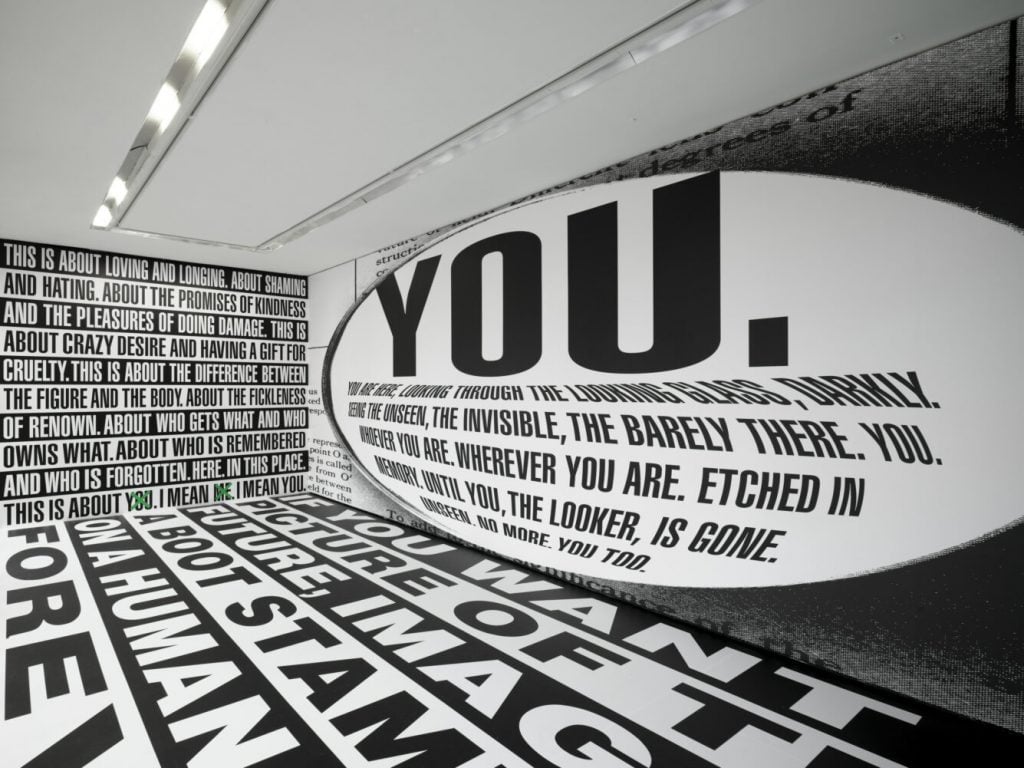

The influence of the internet is present throughout the main show. Unlike the slow-moving, painfully esoteric films that feature frequently in contemporary art museums, Kruger’s newest piece Untitled (No Comment) (2020) is an immersive three-channelled video installation that was born ready to compete in the attention economy. Its unrelenting, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it stream of cats, hair tutorials, flashing slogans, and quotes from thinkers as diverse as Voltaire and Kendrick Lamar manages to simulate the all too familiar feeling of scrolling on our phones “to relax” before bed.

“This digital availability that you have online is just so irresistible and so dominant today,” Kruger said in a recent interview with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Random sounds playing out from speakers in the galleries are intentionally disorienting. “Having rogue audio thread through the exhibition as a sonic intervention was just another way of challenging and adding to receivership,” she added.

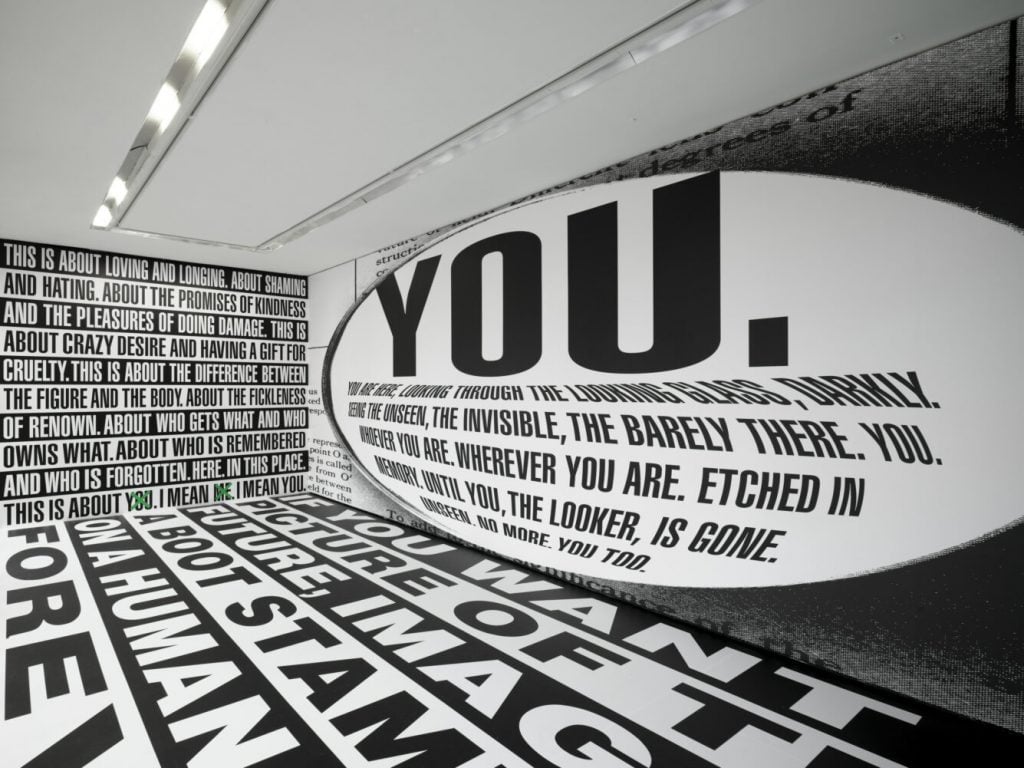

Installation view of “Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.,” on view from February 1 to March 17, 2024 at Serpentine South. Photo courtesy of Serpentine.

Kruger, aged 79, left art school at Syracuse University after just one year and cut her teeth instead working as a graphic designer for magazines in New York during the 1960s. A decade later, she had developed her trademark style of Futura Bold or Helvetic Ultra Condensed font text on black, red, or white banners slapped over black-and-white images. The works had an immediately memorable impact, not unlike that of tabloid headlines. The popular streetwear brand Supreme once admitted in court to being “influenced” by Kruger’s work.

Throughout the London show, one is assaulted with the artist’s directives, flippant propositions, and succinct statements, all of which seem to be a sad reflection on the state of society. Examples like Admit nothing/Blame everyone/Be bitter (1987) are always humorous enough, however, to avoid being too scolding or didactic.

Untitled (Taxis), 2024, outside of Serpentine’s “Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.” Photo: George Darrell.

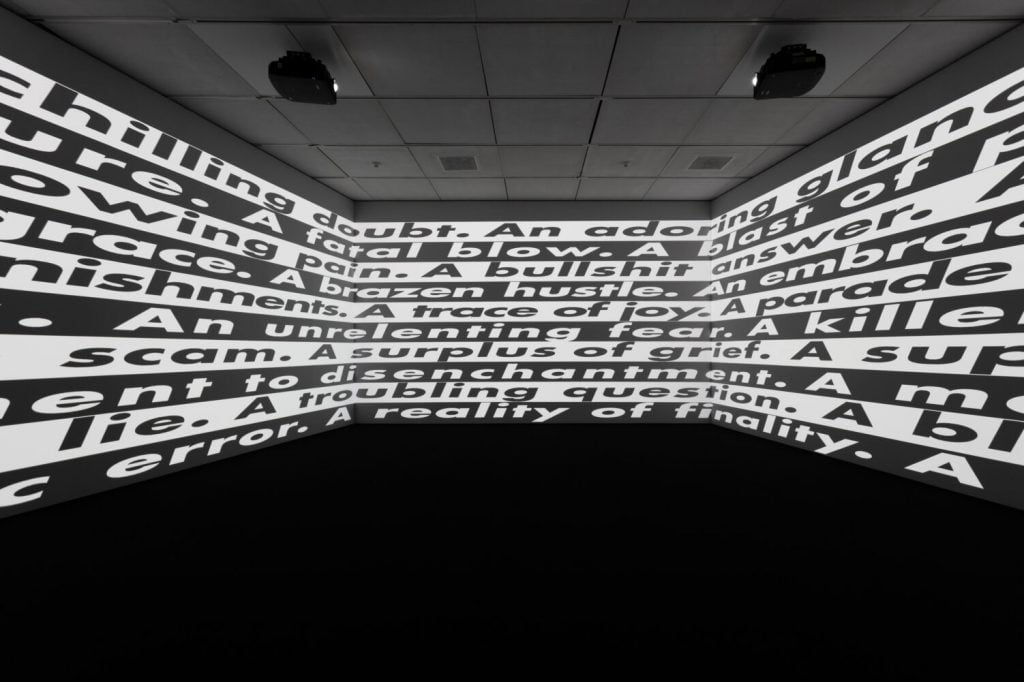

A few of the works have been updated for our present moment through the medium of animation. Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am) (1987/2019), for example, has the words disintegrate on screen before reforming to flash between new variations on Descartes’ infamous philosophical musing like “I shop therefore I hoard,” or “I sext therefore I am.”

Similarly, in Pledge, Will, Vow (1988/2020) Kruger uses a three-channel video stream of classic texts like the U.S. Pledge of Allegiance to highlight the various ways in which a narrative can be constructed. As each word appears on screen, it flickers between several possible alternatives that would imply new meanings ranging from incisive to playfully absurd. “Allegiance,” might therefore become “adoration,” “adherence,” or “anxiety.”

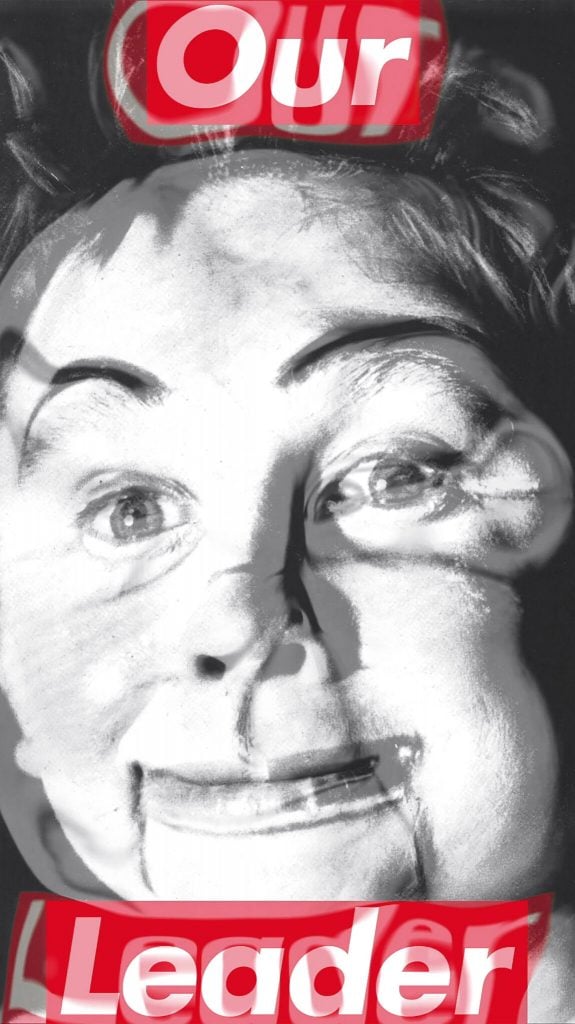

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Our Leader) (1987/2020). Photo courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers.

Kruger’s classic works reinvented for the internet age reveal the technological leaps that have occurred within her lifetime. Yet they also demonstrate that the pace of social change has unfortunately lagged within that same time. For instance, Your Body is a Battleground was originally made for the Women’s March on Washington for reproductive freedom in 1983 but has, if anything, only grown in relevance in recent years.

Similarly, Untitled (Our People are Better Than Your People) (1994) offers a statement of delusional superiority: “Our people are better than your people. More intelligent, more powerful, more beautiful, and cleaner. We are good and you are evil. God is on our side,” and so on. Originally created as sharp satire 30 years ago, today it reads like MAGA-style political talking points nearly verbatim, with very little room for parody.

“It would be great if my work became archaic,” Kruger told Obrist. “But unfortunately, that’s not the case at this point.”

Barbara Kruger’s “Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You” is on view at the Serpentine South Gallery in London’s Kensington Gardens until March 17, 2024.