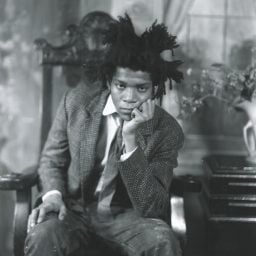

In the mid-1980s, a young Jean-Michel Basquiat, struggling with addiction, rented a studio from Andy Warhol at 57 Great Jones Street. The bar across the street became an unlikely refuge, where the street artist bonded with bartender Randy Gun, a fellow musician and downtown scenester (real name Randy Burns).

“[Basquiat] came in when we weren’t really open yet. I would be setting up between 3 and 4 [pm]. If anyone else tried to come in, I would ask them to come by a little later. But when Jean-Michel came by, I’d let him in,” Gun told art critic (and Artnet News contributor) David Ebony in an interview for an online exhibition from New York dealer Janis Gardner Cecil. “He would have a margarita, straight up.”

“Right above his head where he sat was the original Cassius Clay vs. Sonny Liston poster from 1964. Maybe that’s where they got the idea for the Basquiat and Warhol poster—with them wearing boxing gloves?” Gun mused, referring to the promotion for the artists’ famous 1985 collaborative exhibition at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery.

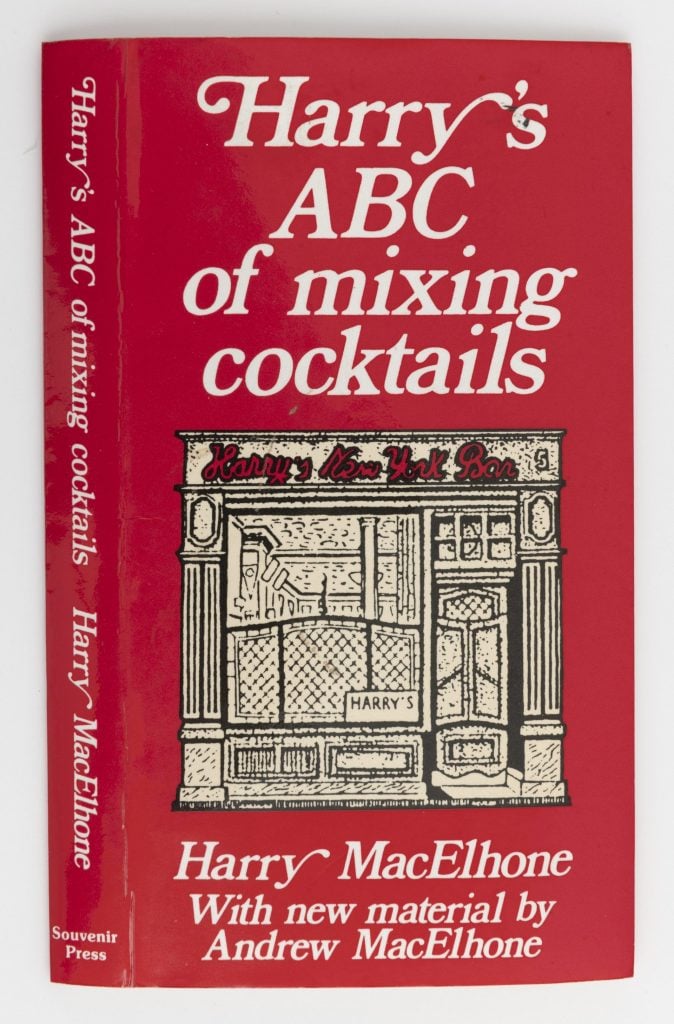

In the show, Gun is sharing with the world for the first time a personal gift that Basquiat—known for his generosity—gave him after returning to New York from a trip not long before his death. The present was the book Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails, from Harry’s New York Bar in Paris, where the Bloody Mary was said to have been invented.

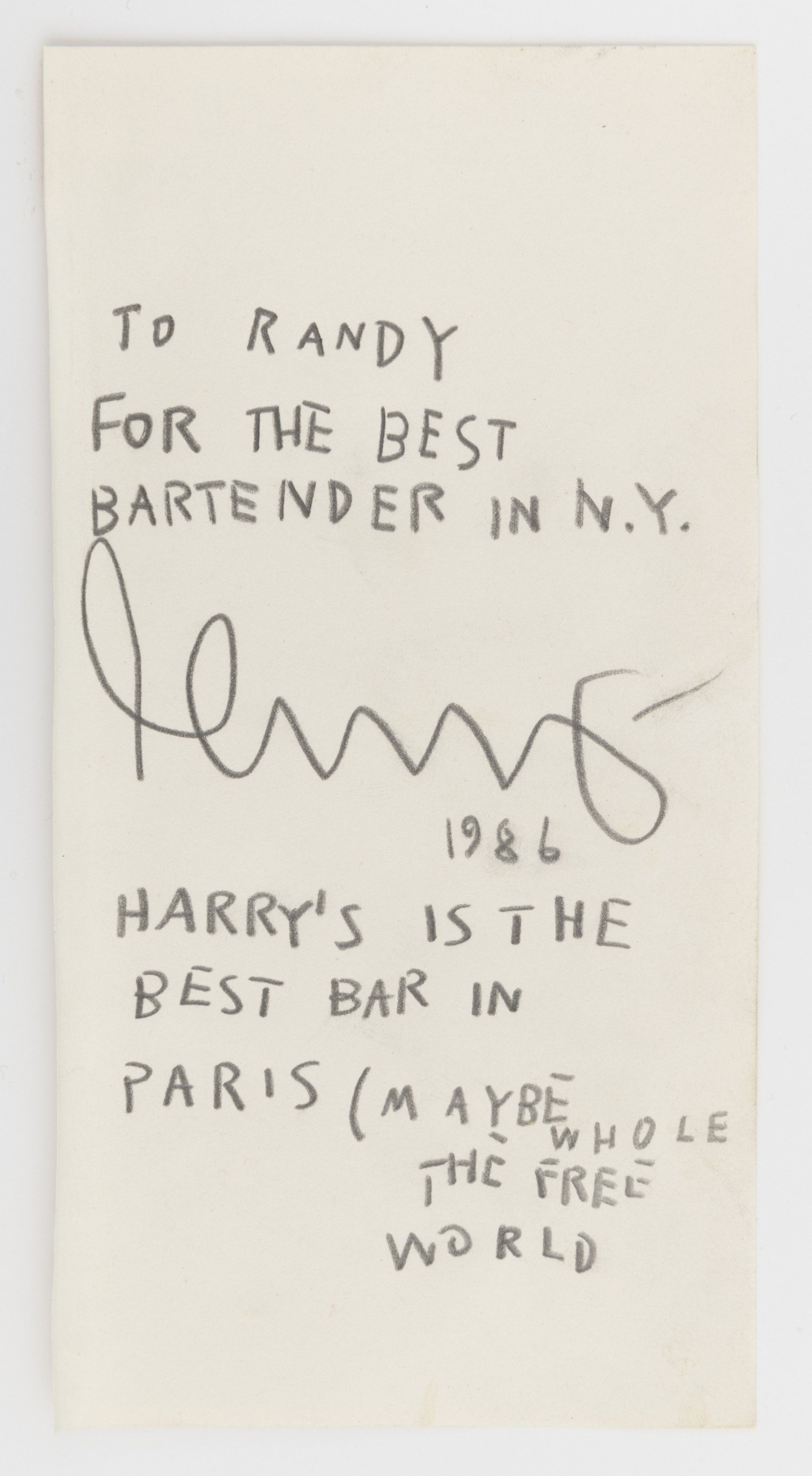

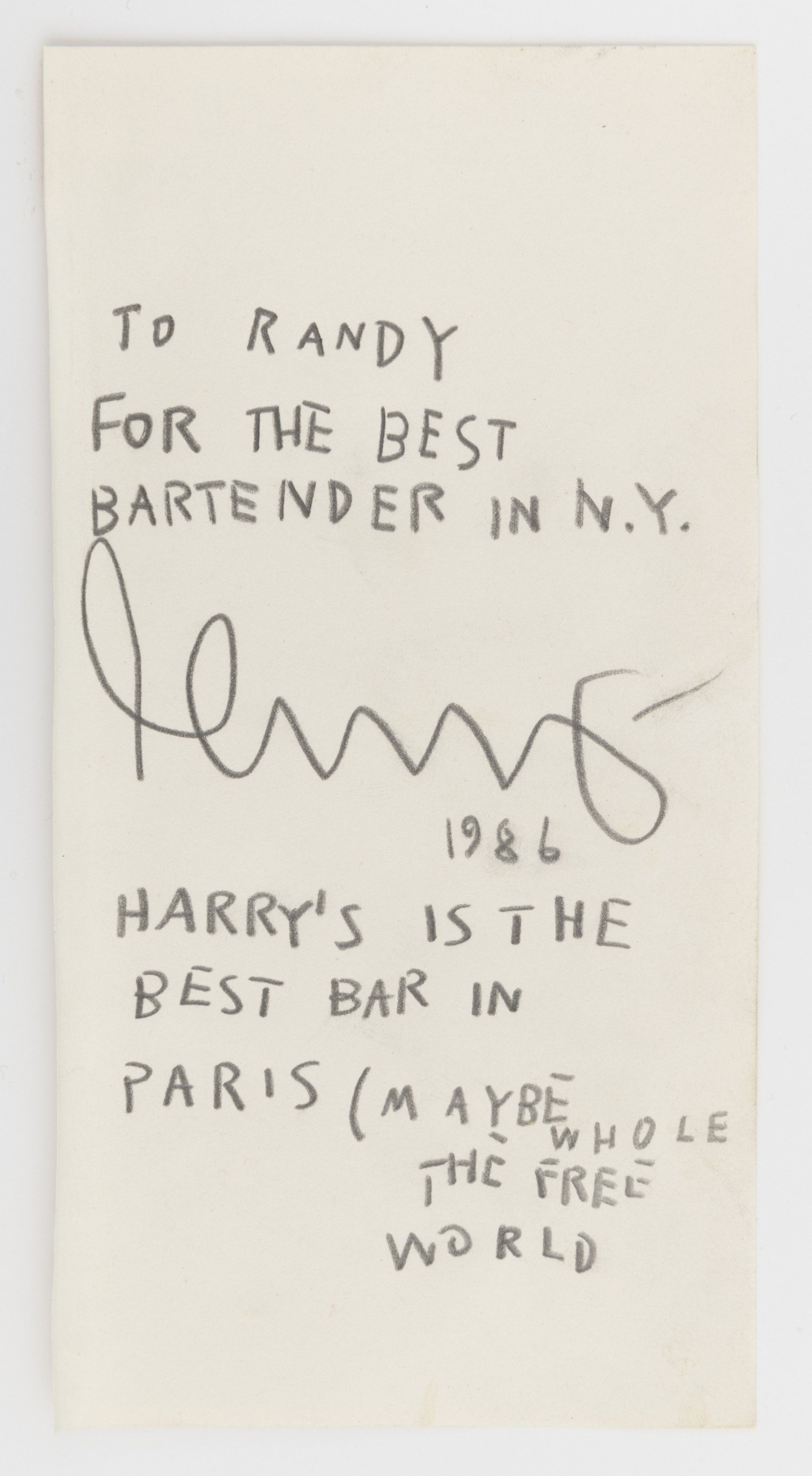

Basquiat hand embellished the copy with six drawings and an inscription reading “To Randy, for the best bartender in New York,” and dated 1986.

Harry MacElhone, Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails: More Than 300 Famous Cocktails (1986), from Souvenir Press Ltd., London. This copy was a gift from Jean-Michel Basquiat to bartender Randy Gun. Photo courtesy of JGC Fine Art.

The artist and the bartender first crossed paths in the late 1970s at bar and nightclubs in downtown Manhattan. Basquiat had cofounded experimental band Gray, while Gun was the guitarist for the punk band the Necessaries. But it wasn’t until a few years later, when Gun was bartending at the Great Jones Cafe, that their acquaintance deepened.

“Sometimes they would chat. Sometimes they would just be there, exchanging atoms in a kind of nonverbal communication,” Cecil told Artnet News. “I think Randy gave Basquiat his space, gave him respect—they obviously built a relationship.”

How Basquiat got his hands on the book, a 1986 anniversary edition of the 1930 tome by a small London publishing house called Souvenir Press (an imprint of Profile Books since 2018) remains a mystery. But the gift underscores the significance of the relationship between the two men, who had both fought to stop abusing the drugs that were so prevalent amid the New York art scene.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails) (1986). A gift from Jean-Michel Basquiat to bartender Randy Gun. Photo courtesy of JGC Fine Art.

“I knew the pain he was experiencing if he was trying unsuccessfully to stop,” Gun told Ebony. “That he came back to visit at the bar after I encouraged him to stop drugging is a testament to his being open to the possibility of change at that time.”

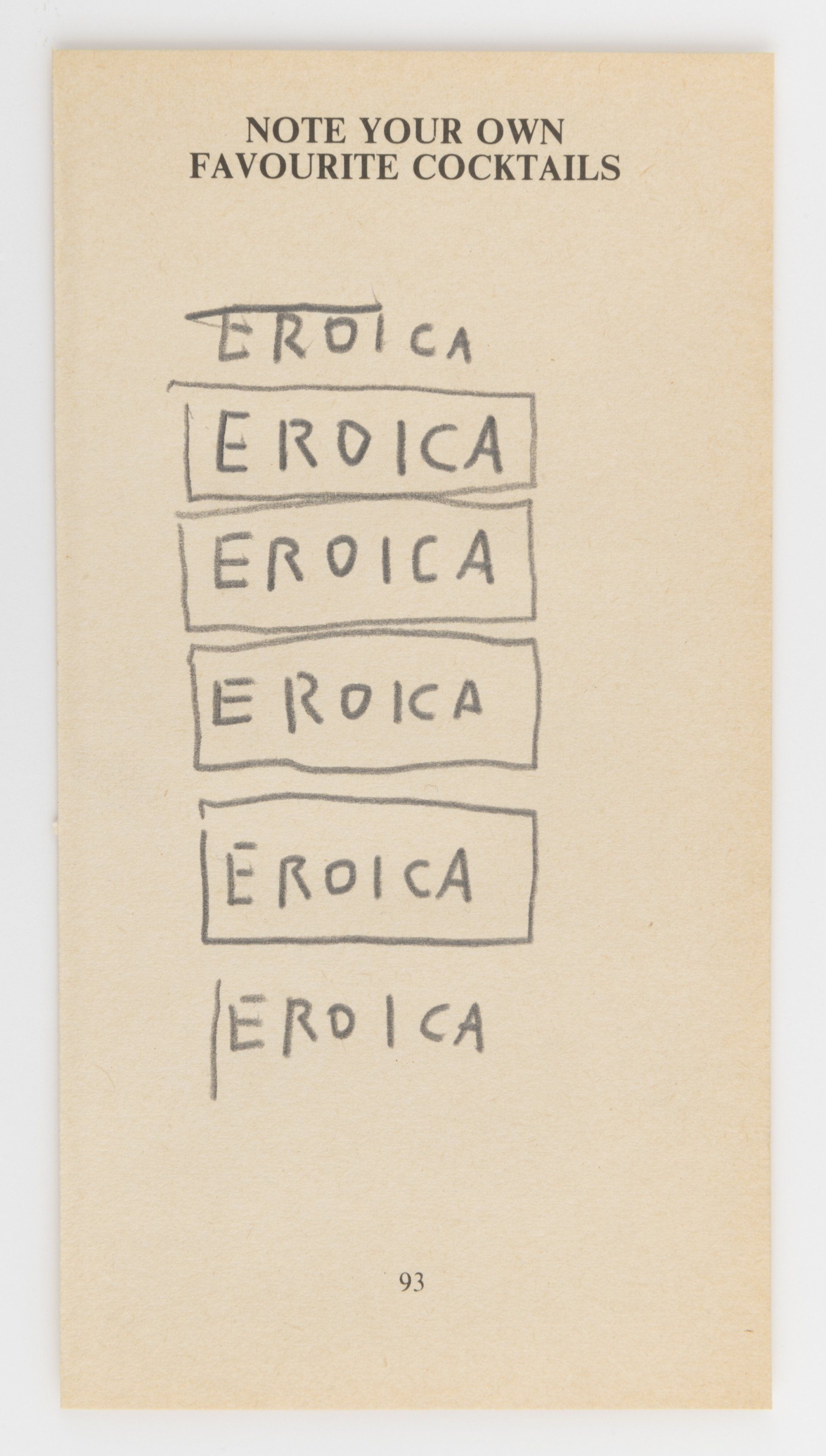

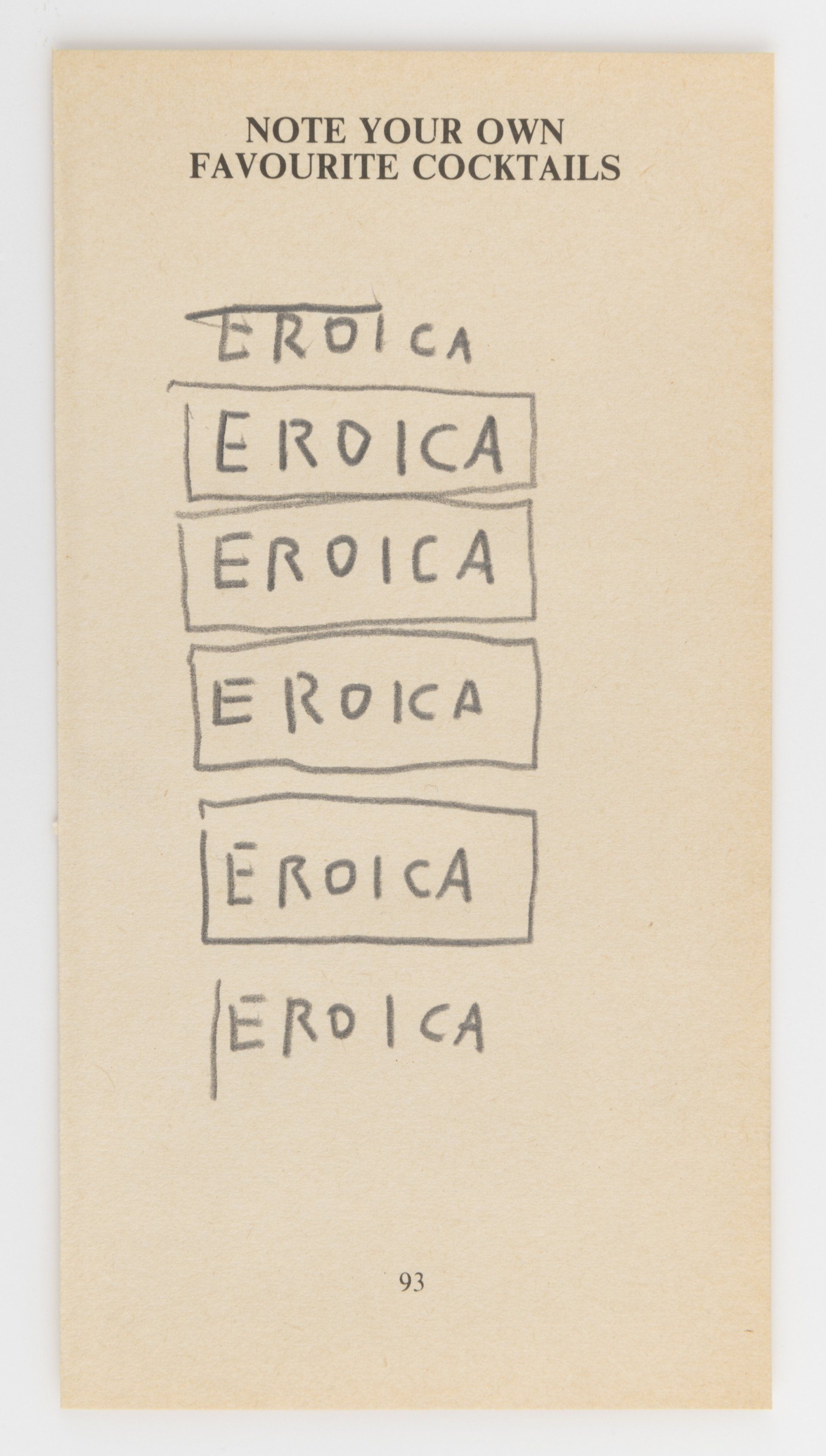

The artworks also feature elements that appear elsewhere in Basquiat’s work, such as the phrase “HONER H,” likely a reference to the harmonica company Hohner; the repeated word “EROICA,” possibly meaning the Beethoven symphony; and a drawing of a Xerox machine, one of the artist’s favorite artistic tools.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails) (1986). A gift from Jean-Michel Basquiat to bartender Randy Gun. Photo courtesy of JGC Fine Art.

A dealer offered Gun a tempting $5,000 for the book shortly after Basquiat’s death. Decades later, his decision to hold off on the sale is likely to prove a prescient one, given Basquiat is now the most expensive U.S. artist of all time. Cecil is hoping to sell the pages from the book, now individually framed, but declined to name a price for the artwork, focusing instead on what it says about Basquiat and the time in which he worked.

“I hope that it illuminates a world that no longer exists in New York, this downtown scene where musicians and artists were polymaths doing lots of different things—that was just what creative people did,” Cecil said.

But the tragic circumstances surrounding Basquiat’s death from an overdose the following year also serve as reminder of the dark side of that creative milieu, she admitted: “As much as it was exciting and creative, it was also dangerous and precarious.”