Art World

Belgian Collector Returns 1,000-Year-Old Wood Carvings to Nepal

"It has restored my faith in the art trade to know that there are still people out there who are willing to do the right thing."

"It has restored my faith in the art trade to know that there are still people out there who are willing to do the right thing."

Adam Schrader

Two wooden carvings have been voluntarily repatriated to Nepal by a Belgian collector. Their return comes amid a rising tide of national restitution claims and guidelines in recent years.

“These important artworks are being returned to Nepal today without judicial proceedings, without law enforcement seizures, without a public shaming, and not so much as our usual arm twisting,” said Art Recovery International founder Christopher A. Marinello, who handled negotiations around the return of the items on a pro-bono basis.

Marinello handed the works over to Gahendra Rajbhandari, ambassador of Nepal to Belgium and the Netherlands, in a March 1 ceremony at the Embassy of Nepal in Brussels.

The two carvings are around 1,000 years old and considered important pieces of Nepalese heritage. One item, a cover for the Illuminated manuscript Shivadharmottara-shastram, is believed to have been stolen from the National Archives of Nepal at some point.

A microfilm image of it was featured in the book Hindu Miniature Paintings of the Kathmandu Valley by Sabitree Mainali in 2009, who wrote at the time that it was believed to “have been lost or perished.”

The other item is a carved wooden sculpture known as a Shalabhanjika Yakshi, which depicts a woman, or female nature spirit, holding onto a tree branch as it bends—a representation of fertility and the prosperity of nature. The sculpture is in the form of a strut, which would have been fastened to the roof above a traditional Nepalese shrine. Such struts are often carved in the form of various gods and goddesses.

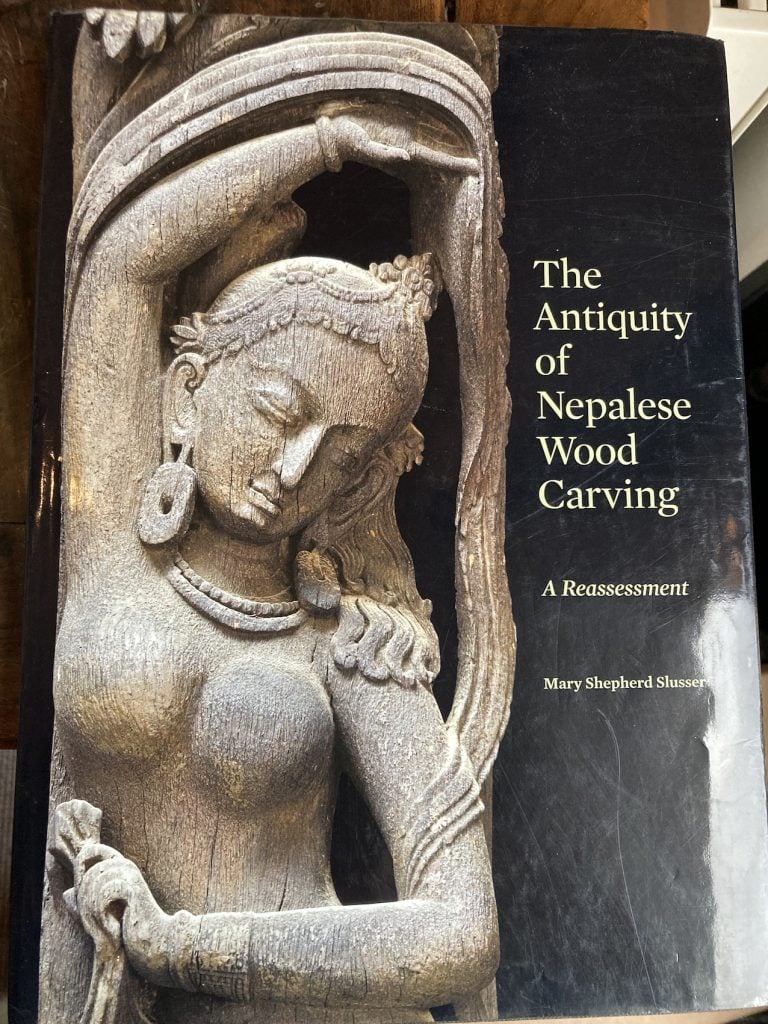

This Shalabhanjika Yakshi strut is believed to have been one of several stolen around 1970 from the Buddhist temple Itumbahah in Kathmandu. The anthropologist Mary Slusser wrote about the struts taken from the temple in her 2010 book The Antiquity of Nepalese Wood Carving. In it, she mentioned that the temple roof collapsed in 1972 and the struts were presumed to have been crushed under the rubble and destroyed.

Mary Shepherd Slusser’s book The Antiquity of Nepalese Wood Carving features one of the wood carvings on its cover. Photo: Christopher A. Marinello.

However, the strut just repatriated to Nepal was also documented by The Huntington Archives in 1970 as one of three that went missing from Itumbahah. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York repatriated one of them in 2022.

The anonymous collector who repatriated the two works had acquired them in the 1990s during a boom in the antiquities trade among Western collectors. Perceptions about such practices and the repatriation of artifacts changed in the decades since, with groups like Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign and The Lost Arts of Nepal leading repatriation efforts in Nepal.

That the collector “simply reviewed the provided provenance and agreed to release the works unconditionally,” reveals a sea change in attitudes toward repatriation, according to Marinello, which has been a hotly contested topic within the art and antiquities trade for decades.

“It has restored my faith in the art trade to know that there are still people out there who are willing to do the right thing without demanding compensation or fees for their attorneys,” Marinello said.

Many European governments have recently introduced guidelines to evaluate restitution claims for objects acquired during colonial periods, among them France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland. In 2021, Germany agreed to unconditionally to transfer 1,100 so-called Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, although it has so far returned only 22.

Last year, in the U.S., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York launched a new unit dedicated to provenance research, following repeated seizures of antiquities by the Manhattan district attorney’s office.