Art & Exhibitions

Watching Art Conservators Work Their Magic Has Become a Hot New Museum Trend. Here’s Why

The Huntington has drawn an enthusiastic audience for its "Project Blue Boy." It's not the only one.

The Huntington has drawn an enthusiastic audience for its "Project Blue Boy." It's not the only one.

Janelle Zara

At the Huntington Art Gallery, a small crowd forms around senior paintings conservator Christina O’Connell’s miniature makeshift arena. As part of “Project Blue Boy,” a year-long exhibition on the restoration of the titular 18th-century Thomas Gainsborough painting, she dabs a pin-thin paintbrush loaded with custom-mixed adhesive on the edges of the canvas. Over the course the next year, she’ll be painstakingly restoring Gainsborough’s “The Blue Boy” to its original splendor, peeling back layers of yellowing varnish, repairing flaking paint, and dusting off decades of dirt and grime.

On Thursdays, Fridays, and first Sundays for the next three to four months, O’Connell will be working in a gallery in front of a live audience, which mainly watches in rapt silence, until she breaks for a 15-minute gallery talk. The Q&A session temporarily transforms the gallery of adult visitors into a classroom of excited children, some waiting patiently with their hands raised, others unceremoniously interjecting with questions: What are those clear pieces of plastic you’re using? Are you worried about dust in the gallery? What painting are you working on next?

An older gentleman in a black cowboy hat compares the precision of O’Connell’s work to that of his surgeon, and asks, “How does it feel to have a responsibility of this magnitude?”

O’Connell frames it as all part of a day’s work. “I’m a steward of all the collections,” she replies. “I have another Gainsborough in my lab right now, and no one’s really excited about that.”

The man in the black cowboy hat wishes her “all the success to make it last for generations to come.”

“Project Blue Boy” installation view. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen Studio. Image courtesy Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington initiative, funded by a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project with additional support from the Getty’s Conserving Canvas initiative, is putting a public face on this normally closed-door profession. But it is not alone.

Chicago-based conservator Julian Baumgartner had his Instagram account surprisingly go viral. The following for his close-up footage of restorations-in-progress has grown by leaps and bounds to 91.1 thousand since he first opened the account in 2016. Similar to “Project Blue Boy,” Baumgartner’s posts create a public arena not just for observing, but for active interaction. He describes its appeal as “process porn.”

“Do you think that the varnish from the surface of the painting should be removed completely?”, one user in Baumgartner’s comments section recently asked, suggesting that the thin layer would add “the effect of antiquity.”

“When you launder your shirts would you prefer they have a thin layer of dirt on them…?”, Baumgartner responded, stressing the difference between fine art and artifact. “If the artist wanted the painting to be ‘dirty.’ they would have paint[ed] it so.”

The intimate look at a normally aloof field is key to the appeal. “For many people, art is kind of magical and mysterious, and it’s also at arm’s length: it’s expensive and elitist,” Baumgartner theorizes over the phone with artnet News. “When you peel back the curtain, it’s a look into how that magic is cultivated and kept alive. That, coupled with [conservation’s] 100 percent analog nature in a digital era, of social media and ASMR—it’s a perfect storm.”

In the gallery, exhibitions like “Project Blue Boy” reveal conservation as an art form in itself, one that combines chemistry, art history, and studio practice, plus a lot of detective work.

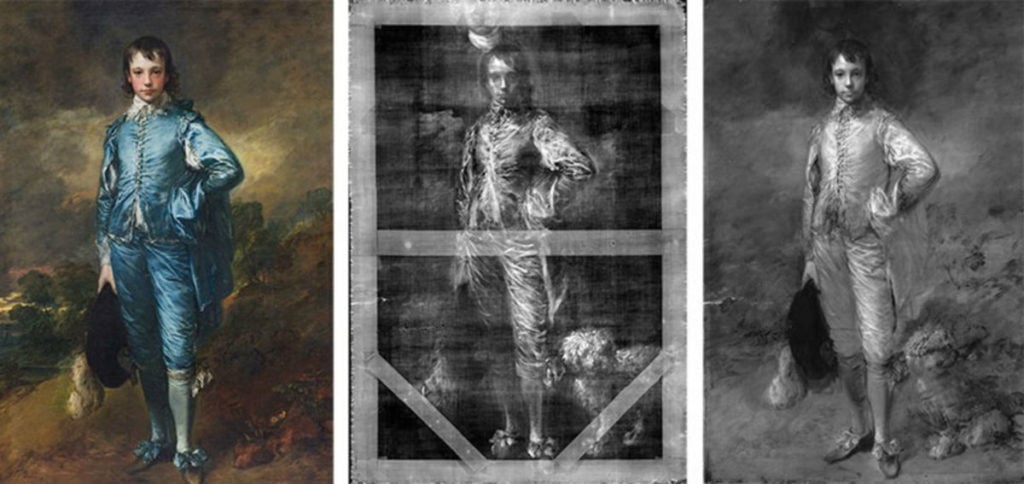

In addition to restoring Gainsborough’s painting, O’Connell’s mission is to build a greater understanding of the British artist’s materials and processes. There’s a lot of potential new information to be gained: X-rays of previous conservations revealed not only an older man’s face but a white dog in previous iterations of the composition.

Thomas Gainsborough, The Blue Boy (ca. 1770) shown in normal light photography (left), digital x-radiography (center, including a dog previously revealed in a 1994 x-ray), and infrared reflectography (right).The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Earlier this year, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles’s offered up Jackson Pollock’s Number 1, 1949: A Conservation Treatment. For this display, conservator Chris Stavroudis was able to offer up a number of new discoveries of his own, in this case about the celebrated Abstract Expressionist. For six months, thanks to the Modern Paints Project of the Getty Conservation Institute, he cleaned the painting Number 1, 1949 (1949) publicly, in the museum.

Beneath the painting’s layers he discovered not only cigarette butts and hidden nails, but the startling fact that Pollock had originally created a much brighter painting that had faded significantly over time. At some point, Stavroudis found, the composition included tendrils of bright cadmium orange.

Installation view of Jackson Pollock’s Number 1, 1949: A Conservation Treatment, courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest.

For Stavroudis, the fact that Pollock had expertly covered the orange by dribbling paint over it was a revelation. “It shouldn’t be a surprise to me, but by this point in his career, he had become an expert in his technique and had tremendous control over it,” he says.

Discoveries like these are the highs of the profession, but it has also had its shares of low, which have also contributed to the public interest. Bad conservation abounds, the most famous instance being Cecilia Giménez’s comically creative infilling of Ecce Homo in 2012. The case was so high-profile that it drew a reference on Saturday Night Live. But contemporary conservators contend with the corrosive effects of lower-profile cases of older treatments with unstable chemicals all the time.

Baumgartner calls such missteps the “uninformed efforts of well-meaning people.” Stavroudis is less generous, stressing that the consequences of bad restoration are very real, sometimes to the point of unethically misrepresenting the artist’s original intentions.

He cites one example of 1960s conservators saturating a Max Beckmann painting with varnish to match the Pop sensibilities of the time. The result literally glossed over the subtle nuances of color that the German Expressionist had intended.

Stavroudis also points to the dull, smoky colors long associated with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes as a result of bad conservators trapping candle soot into the composition with glue. A late 20th-century restoration revealed Michelangelo’s composition to have employed “bright, garish, almost nauseating color to his work”—a big shift in perspective for the public and art professionals alike.

(While some art historians argue that Michelangelo had intentionally dulled his colors, Stavroudis sides with the conservators’ actions here: “Any artist in any period of time isn’t an idiot,” he said during a public Q&A in the gallery this spring. “If you want to paint something with dull colors, you make dull colors. You don’t paint something bright and shiny and put black over the top.”)

Such examples predate modern ethical codes that began to favor minimal intervention in the 1980s, though these present their own dilemmas.

Conservators are now being taught a much narrower repertoire that excludes older, more invasive methods, which means “critical skills in the structural conservation of canvas paintings are disappearing,” according to Getty Foundation senior program officer Antoine Wilmering, explaining the impetus for the Getty’s conservation initiatives.

“Project Blue Boy” installation view. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The possibility of ethical codes changing over the years is a constant in the back of Stavroudis’s mind.

During his own Q&A at MOCA in the spring, he expressed his fears to a museum audience. “I want this treatment to stand up 50 to 100 years so that no one will say he did an okay job, but we would do it better now,” he said.

He described taking comfort in imagining that the painting itself will outlive him. “The highlights of being a conservator and dying,” he quipped, “is that you don’t have to worry about this anymore.”