Ben Enwonwu has long been a household name in Nigeria and in African art circles. Yet it was only three years ago that the late pioneer of African art—often called “the father of African Modernism” and arguably one of the most influential African artists of the 20th century—was rediscovered outside the continent.

At this year’s digital edition of Frieze Masters, the late artist is being shown by the Lagos-based Kó art gallery, which was founded this year by Indian-born collector Kavita Chellaram, who also founded the Lagos-based auction house Arthouse Contemporary.

Twelve Enwonwu works, including oils, works in gouache and on wood, and bronze sculptures, all executed between 1940 and 1980, are included in the Spotlight section of the fair, which features solo presentations by pivotal artists of the 20th century.

“Enwonwu was widely collected until his death and then there was a lull until we put him in our first auction in 2007,” Chellaram told Artnet News.

“Then there was the Bonhams sale in 2013, and ever since his work has gone up in value due to high demand. Through auctions, exhibitions, and private sales, Enwonwu has steadily earned his rightful place in African art history. Now we need more research, documentation, and representation of his work at institutions worldwide.”

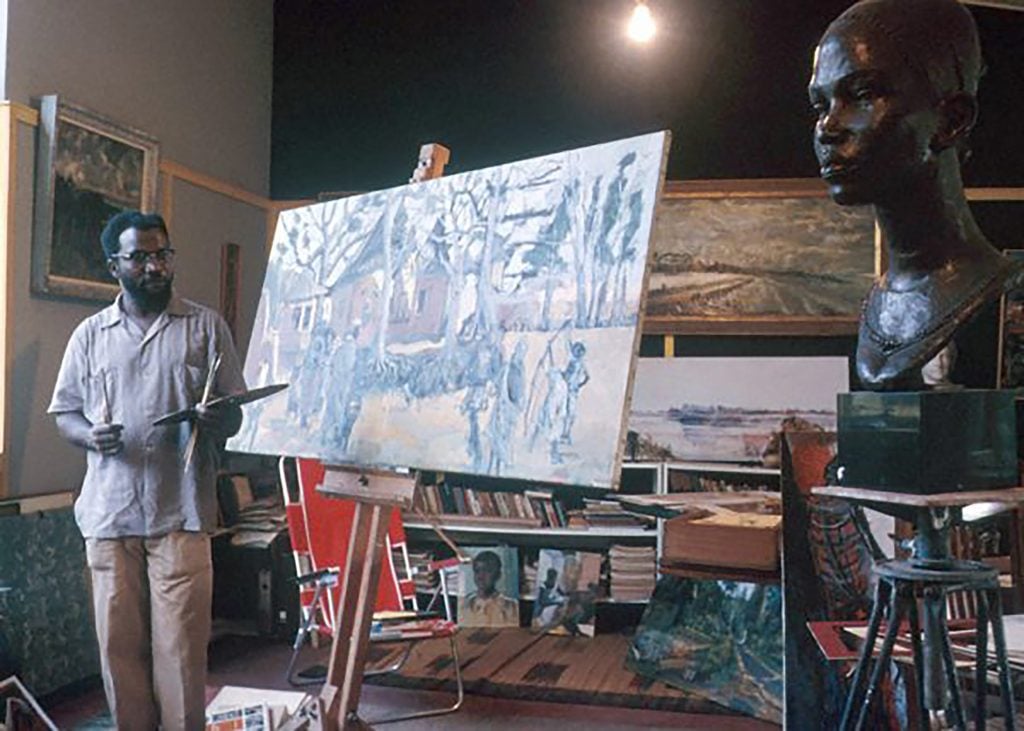

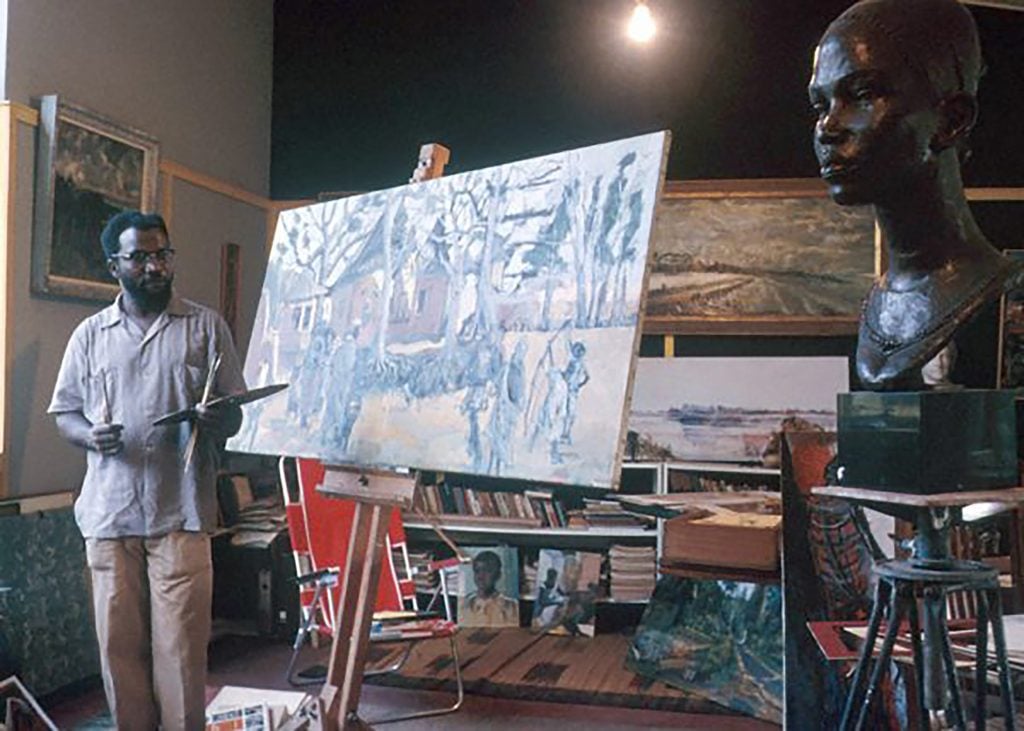

Ben Enwonwu, photo: Eliot Elisofon. Courtesy of the Ben Enwonwu Foundation.

A Cosmopolitan Background

Born in 1917, Enwonwu believed throughout his life that a modern Nigeria needed to be rooted in its own heritage and culture. Growing up in Onitsha, a cosmopolitan market town that was a center of indigenous Igbo culture and British colonial rule, he based his art on a complex amalgamation of visual imagery and systems of representation, borrowing from local traditions and foreign culture. By 1950, his artworks had been exhibited in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the US.

“Enwonwu was probably the first African artist to gain international acclaim and really laid the groundwork for contemporary African art,” said Hannah O’Leary, head of Sotheby’s African art department.

“He was discussing and debating what it means to be an ‘African artist,’ and what is ‘contemporary African art’—discussions that continue to the present day.”

The Nigerian artist’s show at Frieze Masters marks the third time his works have been presented internationally since his death in 1994. (He was also the subject of a 2004 exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute in London to mark the 10th anniversary of his death, as well as an exhibition at GAFRA Gallery in London in 2015.)

Ben Enwonwu, Africa Dances (1957). Courtesy of kó Gallery.

The selection presented by Kó focuses on several recurring themes in the artist’s oeuvre—performances, dances, and masquerades—reflective of the Negritude and Pan-Africanist movements.

Included in the fair are works from Enwonwu’s “Africa Dances” series, which he began in the 1940s and which emphasize the primacy of dance and performance as central elements of African and African diaspora cultural representation.

There are also works from the artist’s long-time Negritude series, which reflect the movement (which Enwonwu joined) that was founded by Senegalese poet, politician, and cultural theorist Léopold Sédar Senghor.

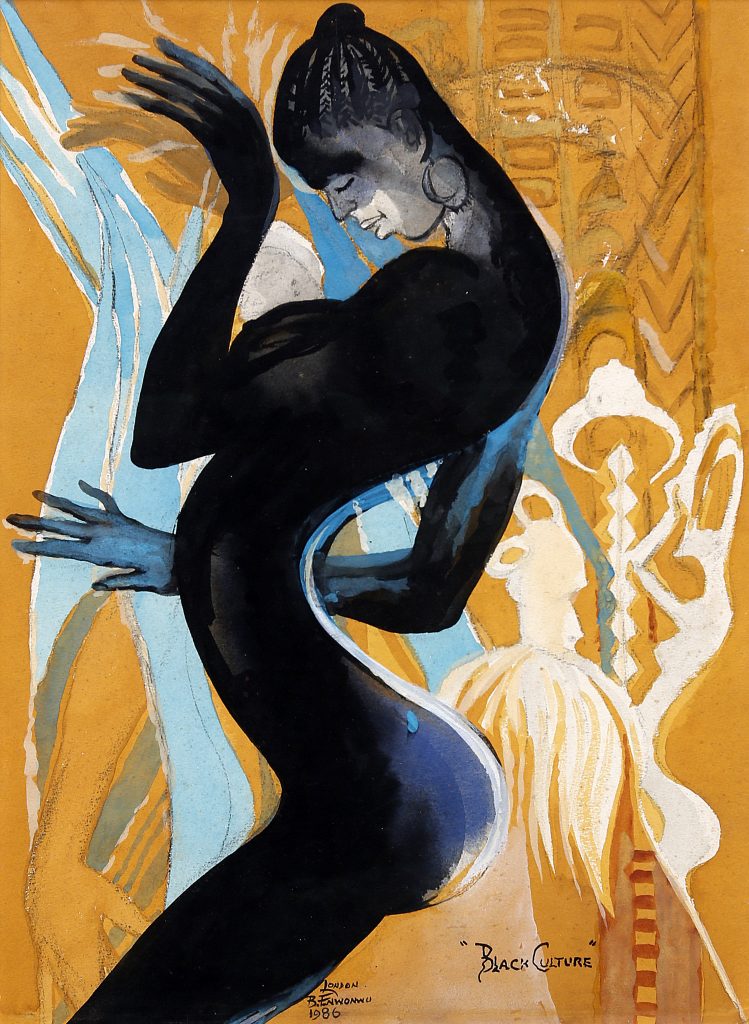

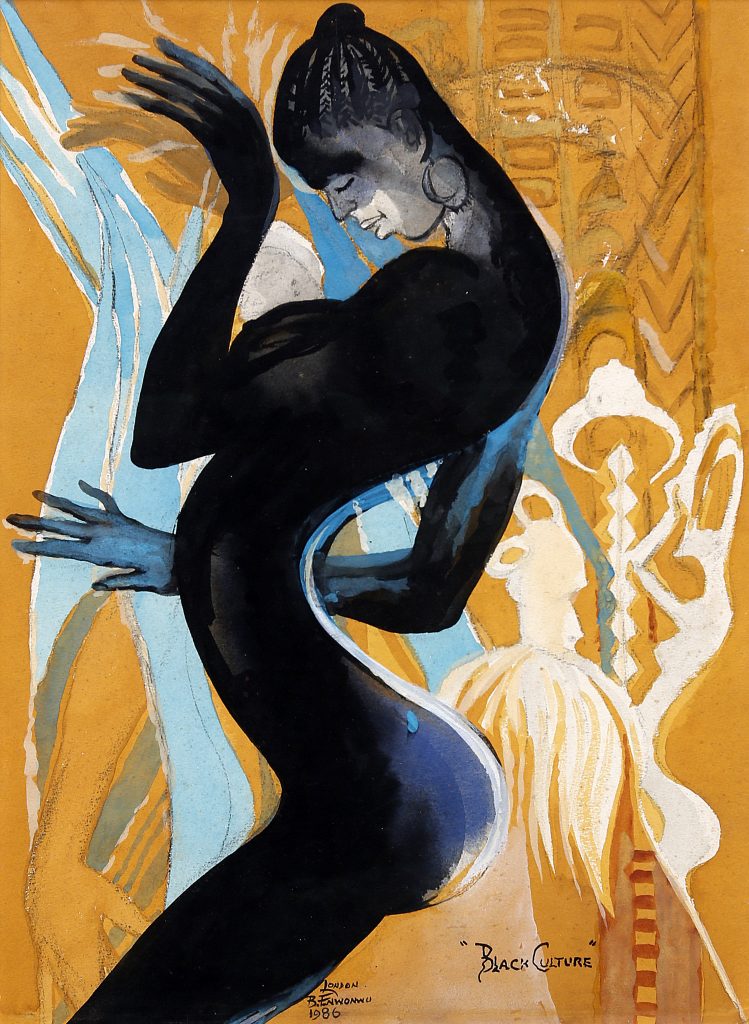

In Enwonwu’s 1986 work, Black Culture, he references the ideology of Negritude, suggesting an affinity with the artists of the Harlem Renaissance, which he encountered during his exhibition tour in the US in 1950.

Ben Enwonwu, Black Culture (1986). Courtesy of kó Gallery.

Enwonwu was part of an intellectual movement that pushed for a unified Nigerian culture before independence. What many do not know is that he was also a prolific writer and art critic.

“By 1946, he was exhibiting in a group show in Paris with Picasso, which was quite amazing for an artist who had never left Nigeria until two years prior,” Neil Coventry, a representative for Bonhams Nigeria, told Artnet News.

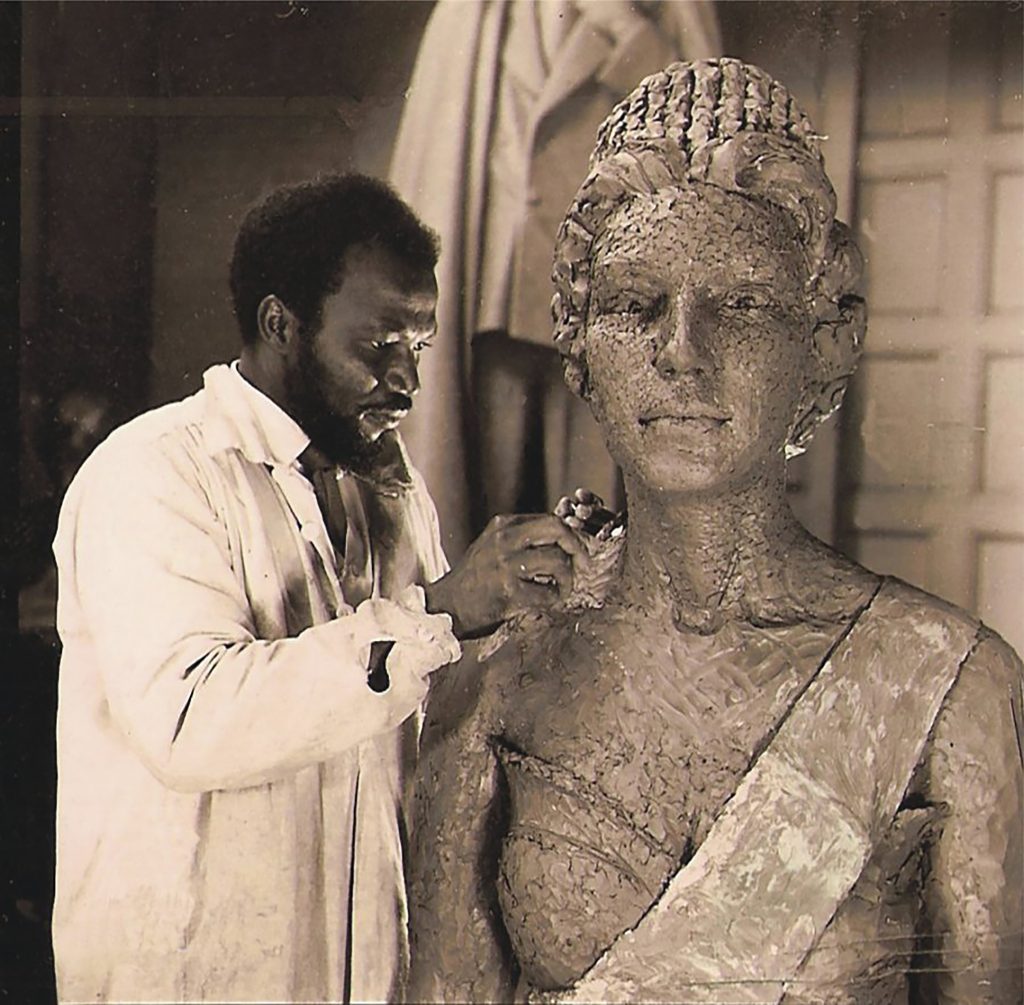

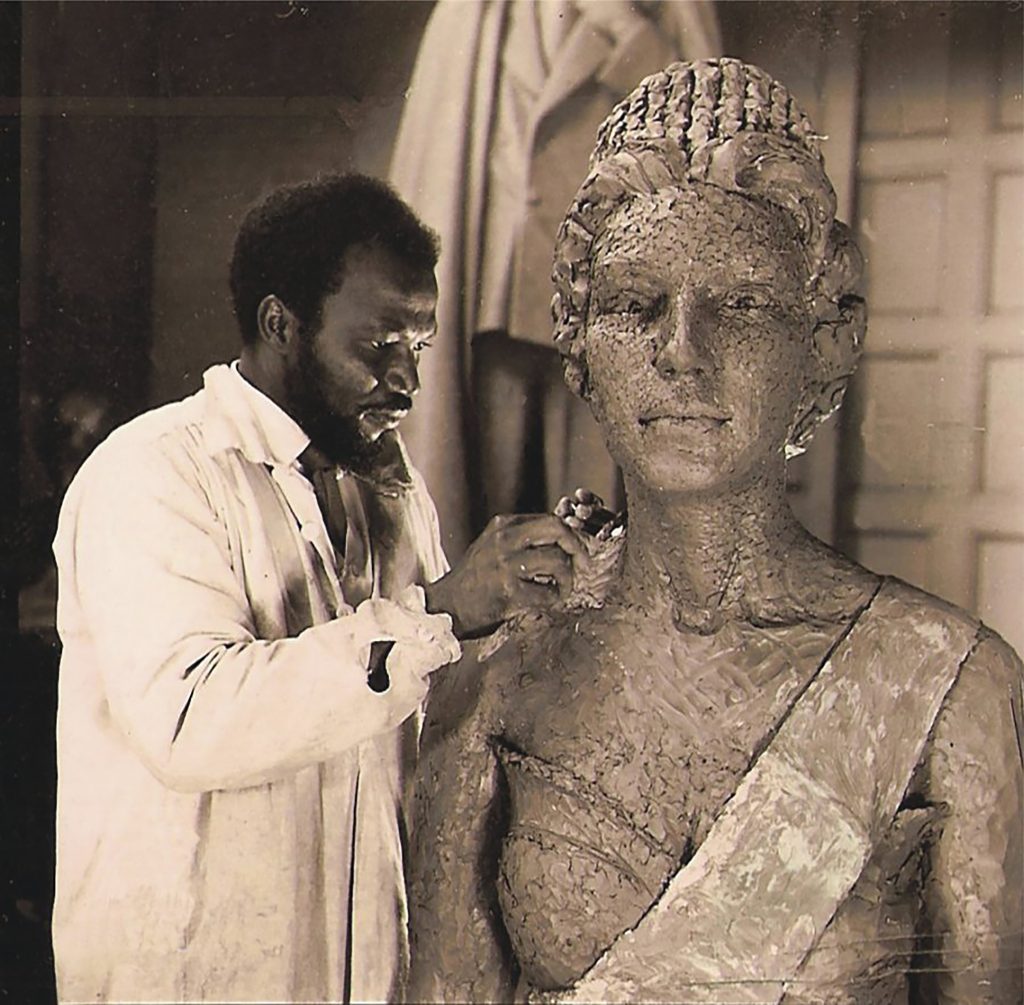

“In 1956 Enwonwu was commissioned to sculpt Queen Elizabeth, making him the first African artist asked to do so. He made huge strides, really mixing with the artists of the day.”

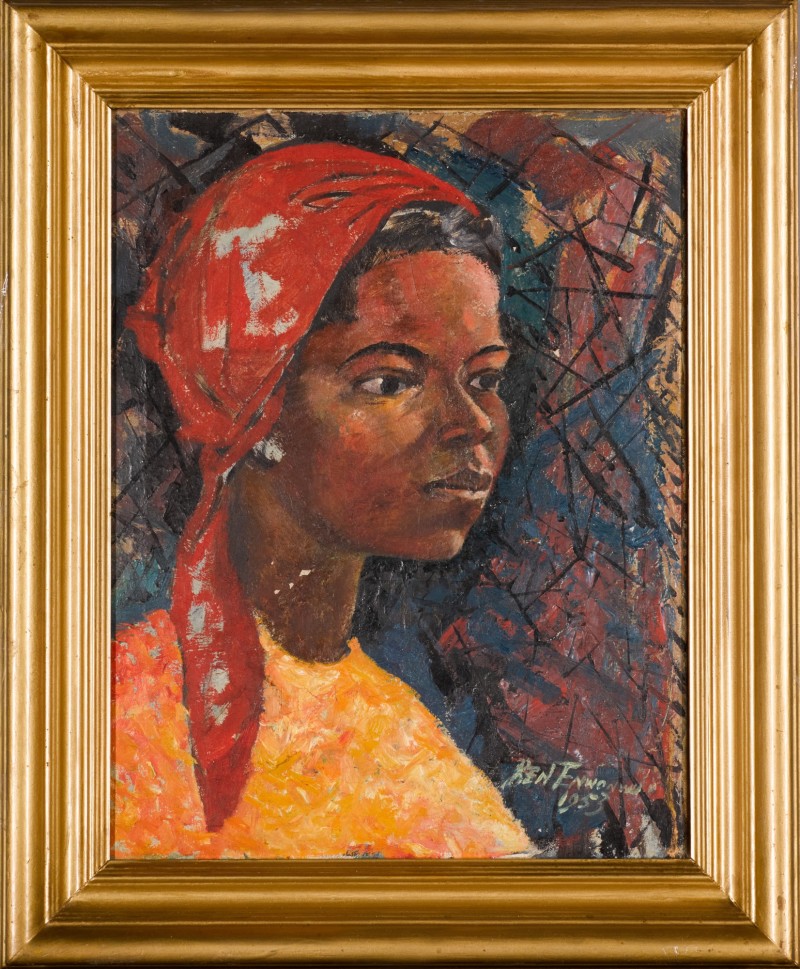

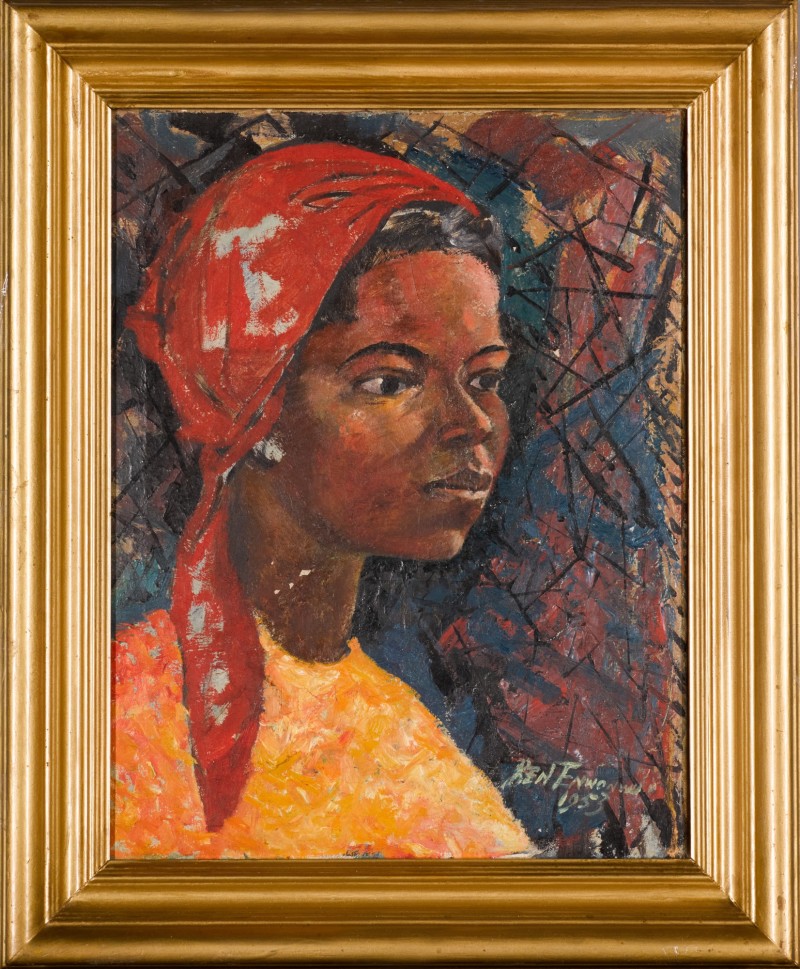

Ben Enwonwu, Regina (1953). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The Market Grows

The past three years have demonstrated increased international attention to Enwonwu’s work, propelled by a recent upsurge in interest in Modern and contemporary art from Africa. According to the Artnet Price Databae, the global auction sales volume of Enwonwu’s works rose from just over $2 million in 2017 to $5 million in 2018, although it dipped slightly the next year.

Until 2013, the auction record for a work by the artist was £361,250 for a series of wooden sculptures sold through the Bonhams Africa Now sale. Then, in February 2018, the artist’s portrait Tutu sold for £1.2 million ($1.7 million) at Bonhams London, setting a new auction record for the artist. The painting, which depicts Nigerian royal princess Adetutu Ademiluyi, had been missing for 40 years and was found in a London apartment.

The market continued to roar in October 2019, when Sotheby’s sold a 1971 portrait by the artist titled Christine for £1.1 million ($1.4 million), leaping well beyond its pre-sale high estimate of £150,000 ($192,000).

Enwonwu working on a bronze sculpture of Queen Elizabeth II. Courtesy of the Ben Enwonwu Foundation.

Nor has the interest abated since. On October 9, at a Sotheby’s sale of Modern and contemporary African art, Enwonwu’s portrayal of his 19-year old niece, Regina, nearly quadrupled its pre-sale estimate of £40,000 to £60,000 to a final price to £238,971 ($308,608). In the same sale, a sculpture from his “Africa Dances” series achieved five times its estimate of £25,000 to £35,000 to land at £176,084 ($227,395). Eight additional works by the artist also sold, with over half selling above their high estimates.

“His most sought-after works have definitely been his portraits, with Christine and Tutu having fetched over £1 million each, and even the small Regina attracting 27 bids to soar from its low estimate,” O’Leary told Artnet News.

While the increase in visibility and value for the artist’s work should hardly be surprising for a pioneering artist, what remains missing is a large-scale retrospective. But now may be the right time.

“An exhibition of this nature will have to happen eventually,” Coventry said. “The artist is too important for it not to.”