In between his many accomplishments—inventing the lightning rod, founding the University of Pennsylvania, drafting the Declaration of Independence—Benjamin Franklin also devised innovative and secure ways to print money, new research has found.

From 1730, the polymath printed almost 2.5 million notes for the American Colonies as part of efforts to establish an independent monetary system intended to replace gold and silver currency. The money was printed using Franklin’s network of printing presses (a “very profitable Jobb,” he called it), one of which also published the Pennsylvania Gazette.

A collection of these colonial notes is now held by the Hesburgh Libraries at the University of Notre Dame, about 600 of which have been analyzed by researchers from the school’s Department of Physics and Astronomy over the past seven years.

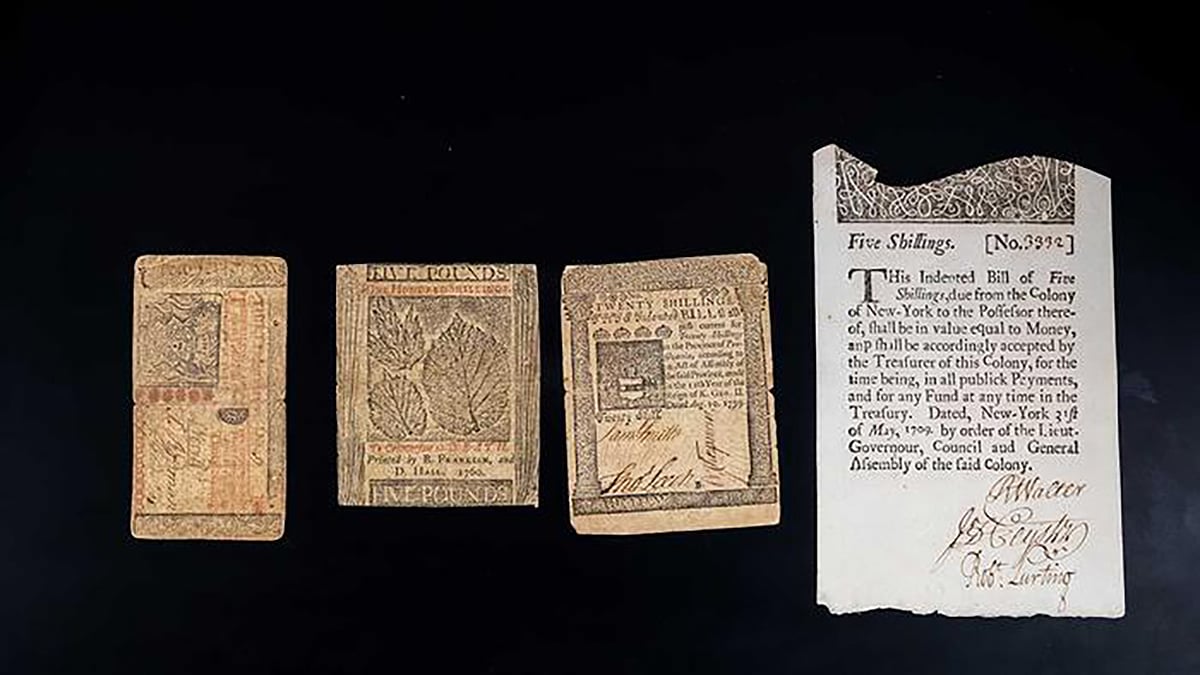

Paper currency printed by Benjamin Franklin and his partner David Hall (1779). Photo: Library of Congress.

Because the ledger where Franklin recorded his printing methods has been lost, the team used spectroscopic and imaging technology to study the inks, papers, and fibers of the surviving notes. Among their findings were the original techniques he used to solve the biggest problem when it comes to printing money: counterfeiting.

“To maintain the notes’ dependability, Franklin had to stay a step ahead of counterfeiters,” said Khachatur Manukyan, the lead researcher, in a statement. “Using the techniques of physics, we have been able to restore, in part, some of what that record would have shown.”

Khachatur Manukyan and his team employed cutting-edge spectroscopic and imaging instruments to get a closer look at Benjamin Franklin’s bills. Photo: Barbara Johnston / University of Notre Dame.

Franklin’s notes were printed with a special black dye, created from rock graphite, unlike counterfeiters who resorted to using “bone black” dye, made from burned bone in their fake bills. Where the counterfeit notes contained high quantities of calcium and phosphorus, the researchers found the real money only held traces of these elements.

The genuine bills were also printed on paper integrated with colored fibers that turn up as pigmented squiggles and a translucent material that the scientists have identified as muscovite. The team found that the use of the mineral increased over time, likely because it made the printed notes more durable and harder to replicate.

These methods were in addition to Franklin’s use of “nature printed” patterns—raised designs that were cast from leaves—and paper watermarks to deter counterfeiters.

“These features and inventions made pre-Federal American paper currency an archetype for developing paper money for centuries to come,” wrote the researchers in their paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Fittingly, a portrait of Franklin, created by French painter Joseph Duplessis, would grace the United States’ $100 bill, still the largest denomination in circulation, beginning in 1914. In recent decades, microscopic printing around the image, as well as a watermark of Franklin, have been introduced as part of modern-day anti-counterfeiting measures.