Art World

In Five Short Years, the Berlin Program for Artists Has Helped Dozens of Art-School Graduates Find Their Way. Now, It Faces an Uncertain Future

After losing a key grant, the program's administrators are looking for a path forward.

After losing a key grant, the program's administrators are looking for a path forward.

Kate Brown

The halls of the Gropius Bau in Berlin are unusually quiet and the lights are mostly off these days, as museums in Germany remain closed. Last fall, however, there was a buzz inside, as young artists set up temporary studios at the invitation of the museum’s administrators.

The Berlin Program for Artists, a nomadic mentoring program founded in 2015, had been installed there for three months. On the day of my visit, Swiss-American artist Anne Fellner had several canvases laid out on the floor and pinned to a wall. Former program participant and 2020 guest mentor Elif Saydam stood with Fellner, talking about the works and catching up.

Through the echoing galleries, program co-founder Angela Bulloch and participant Nadja Abt had another conversation that could be heard as a hum. The chopped landscape of Berlin—the Topography of Terror monument is just below the Gropius Bau, with a Nazi-era parliamentary building across the street and glass high-rises in the distance—was visible just outside. Yet the landscape is changing, and the spry and transmutable organization is trying to forge a path amid shifting tectonic plates of financial realities.

BPA group meeting in Monika Baer’s exhibition at nbk, Berlin (2020).

Berlin has long attracted fledgling artists looking for space, leading to an astoundingly diverse art scene in the years since the fall of the Wall. BPA, as the two-year program program is commonly known, was founded five years ago by Bulloch and artists Simon Denny and Willem de Rooij with that cohort in mind. The three artists, who are also teachers, felt that post-graduate years can often be particularly isolating for artists; to combat that, they established something like a residency program with no residence requirement, focusing primarily on fostering conversations among artists.

“After graduating, it’s not uncommon to follow a singular path and lose that proximity to practices that diverge from one’s own,” says artist Adam Shiu-Yang Shaw, a second-year participant who completed his MFA at the Royal Academy in Sweden. “The program comprises distinct positions, some of the participants occupying rather disparate pockets of the community.”

The program exists largely behind the closed doors of artists studios around the city, a place where a room of one’s own is increasingly hard to come by—since 2015, when BPA launched, rent has increased by 30 percent in Berlin. What’s more, despite its ties to institutions and prominent figures in Berlin (among the program’s mentors are Wolfgang Tillmans and Olaf Nicolai), BPA is caught in a surprising state of precariousness as well. Come March, funding may dry up completely.

“We are very worried right now,” says de Rooij. “We cannot put our program on hold for even a year, because the needs of participants are not put on hold either. Their needs for connection and exchange don’t become less [pressing]. Substantial, consistent, and longer-lasting support is essential.”

Artists Willem de Rooij, Angela Bulloch, and Simon Denny, co-founders of the Berlin Program for Artists. Photo: Piero Chiussi.

The program started out as a whisper, with ten participants meeting mentors in one anothers’ studios. In the past few years, BPA has evolved into a public-facing enterprise with perennial exhibitions and a talks program, the latter taking place at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art. It is a desirable format, last year, around 200 artists applied.

“Because we are artists, we constantly question the program, so it is always growing, merging, and moving,” says de Rooij, who is Dutch and teaches at the Städelschule in Frankfurt. His colleagues are also transplants and professors: Bulloch, who is Canadian, teaches alongside Denny, who is from New Zealand, at the Fine Arts School in Hamburg.

The trio noticed a typical pattern among art-school graduates: many move to a larger city, look for a studio, try to make some money, and ideally land shows and find other kinds of support. But the course is often indirect, and may last up to a decade.

“We know the challenges young artists face after finishing school, and we know what kind of support is needed in these years,” de Rooij says. “Institutionalized formats for artists to ‘learn on the job’ exist in other countries, but not in Berlin or in Germany.” And while comparable models, like the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York, do exist, BPA is different in that it charges no tuition, has no set roof over its head, and focuses specifically on local artists.

As part of the program, participants are invited to visit the studios of artists who would otherwise be less accessible, such Katharina Grosse, who has a pair of factory-like spaces with full-time staff. Intra-artists conversations are not the only exchange; mentors may include art writers or curators, like KW’s director Krist Gruijthuijsen who was a guest mentor last year.

“Certain hierarchies are inherent to the workings of an art school,” de Rooij says by way of contrast. “At BPA, we opt for a more reciprocal form of exchange.”

Discussions are meant to be loose, horizontal, and focus on how the art is made and what questions artists ask themselves while working. “It is not about pedagogy because most mentors are not necessarily coming in with a teaching background,” says Saydam, the former participant and current mentor. “They are peers at a different stage in the same trajectory.”

Dina Khouri’s Painting at a Loss Lagos 1 (2019). Installation view BPA at Gropius Studios: Dina Khouri and Katrin Winkler, 2020.

Throughout the years, the school’s lean overhead has been paid for through state funding. That includes mentors are paid for opening their doors for studio visits, and program participants are paid to take part.

But now, the program’s organizers need to pivot. In December, they learned that a crucial government grant had been denied, meaning money would be unusually tight in an already difficult terrain.

The Berlin senate for culture, which has been doling out the grants, was not able to provide a specific answer on why the program would not be funded this year, even as it emphasized that there was no less money available than in a previous grant cycle.

“We can clearly observe how it becomes harder each year for artists to find working space in the city’s centers,” says de Rooij. “If Berlin continues to push artists out to the peripheries, it will influence the artistic infrastructure, but also the larger social fabric of the city. In other European capitals we see how monocultural city centers became devoid of innovation.”

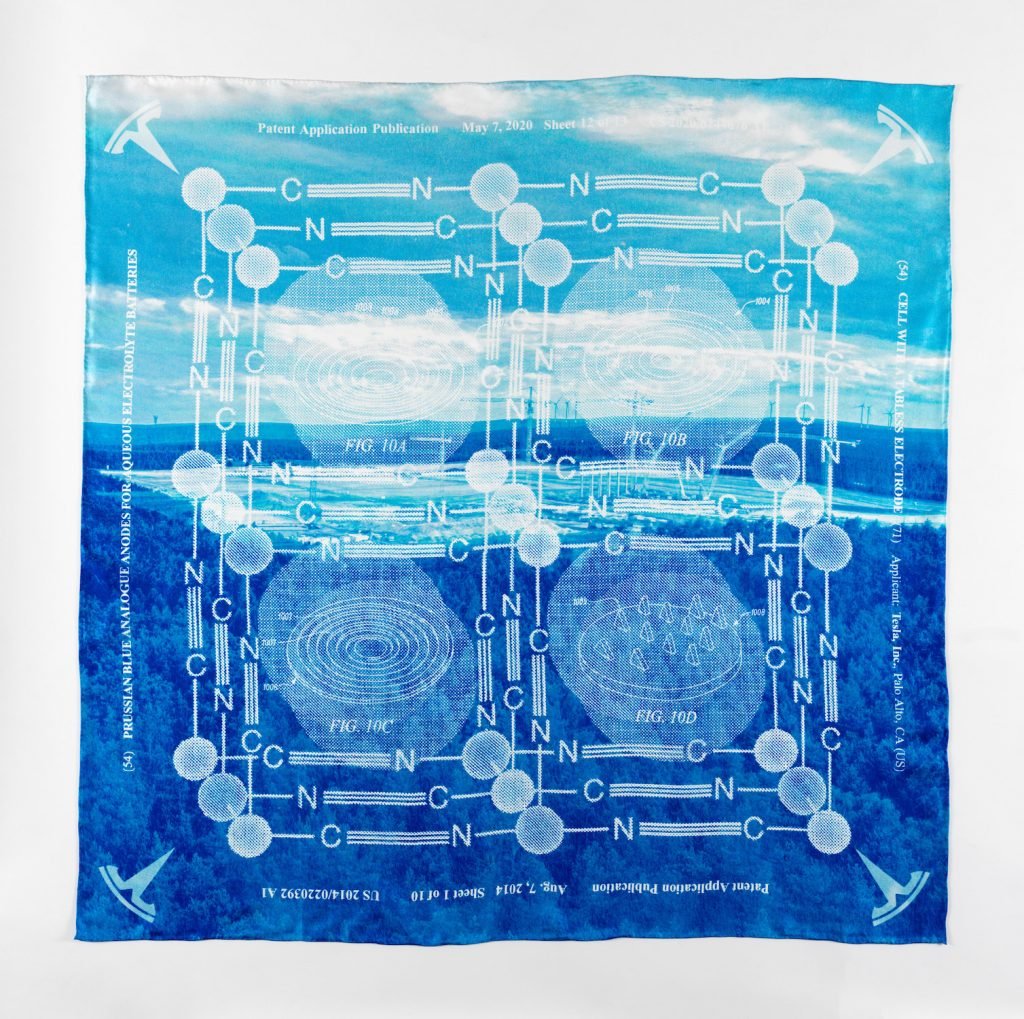

Simon Denny’s printed silk scarf Berlin Blue (2020), with proceeds to benefit the Berlin Program for Artists, is currently available.

With that in mind, the program’s founders are determined to continue, and are already testing out alternative funding formats, including a private patronage system. Denny has also made a limited-edition silk scarf depicting the Tesla factory that is currently under construction on the city limits. The design is a reminder of the complicated forces pulling at Berlin, of an incoming tech class that may further suffocate the city’s dynamism.

No matter its future, BPA’s participants and mentors agree on the benefits it has already provided.

“The interactions in BPA are cumulative and mean more over time,” Saydam says. “It all feeds back into the art scene. On a networking level, the benefit is clear. But on a social level, having an infrastructure where you know you will see certain people regularly, that becomes more about community.”