People

Artist Beverly Pepper, Who Long Rejected Critics’ Attempts to Define Her Brawny Sculptures, Has Died at 97

The Brooklyn-born artist died in her adopted hometown of Todi, Italy.

The Brooklyn-born artist died in her adopted hometown of Todi, Italy.

Taylor Dafoe

Beverly Pepper, the sculptor of mammoth artworks who refused to be tied to any groups or circles, died on Wednesday in Todi, Italy, at the age of 97.

The artist died at her home, where she had lived with her husband, the journalist Curtis Bill Pepper, since the early 1970s. The news was confirmed by her daughter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jorie Graham.

Long considered one of the most powerful artists of her generation, Pepper shunned typical classification, leaving confused critics to lump her in with the Abstract Expressionists, Kinetic artists, and Land Art pioneers. They even called her a late Constructivist.

Beverly Pepper in 2009. Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Pepper was known for working with the kind of hefty, industrial media—iron, stone, and Cor-Ten steel—usually associated with brawny male sculptors like Richard Serra and David Smith. Yet she retained a sense of buoyancy and grace that belied the heaviness of her chosen craft.

She was born Beverly Stoll, the daughter of Jewish immigrants, in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn in 1922. She graduated from James Madison High School and studied design at the Pratt Institute before working as an art director in advertising agencies. The work was unfulfilling, however, and she spent her nights taking art history classes at Brooklyn College.

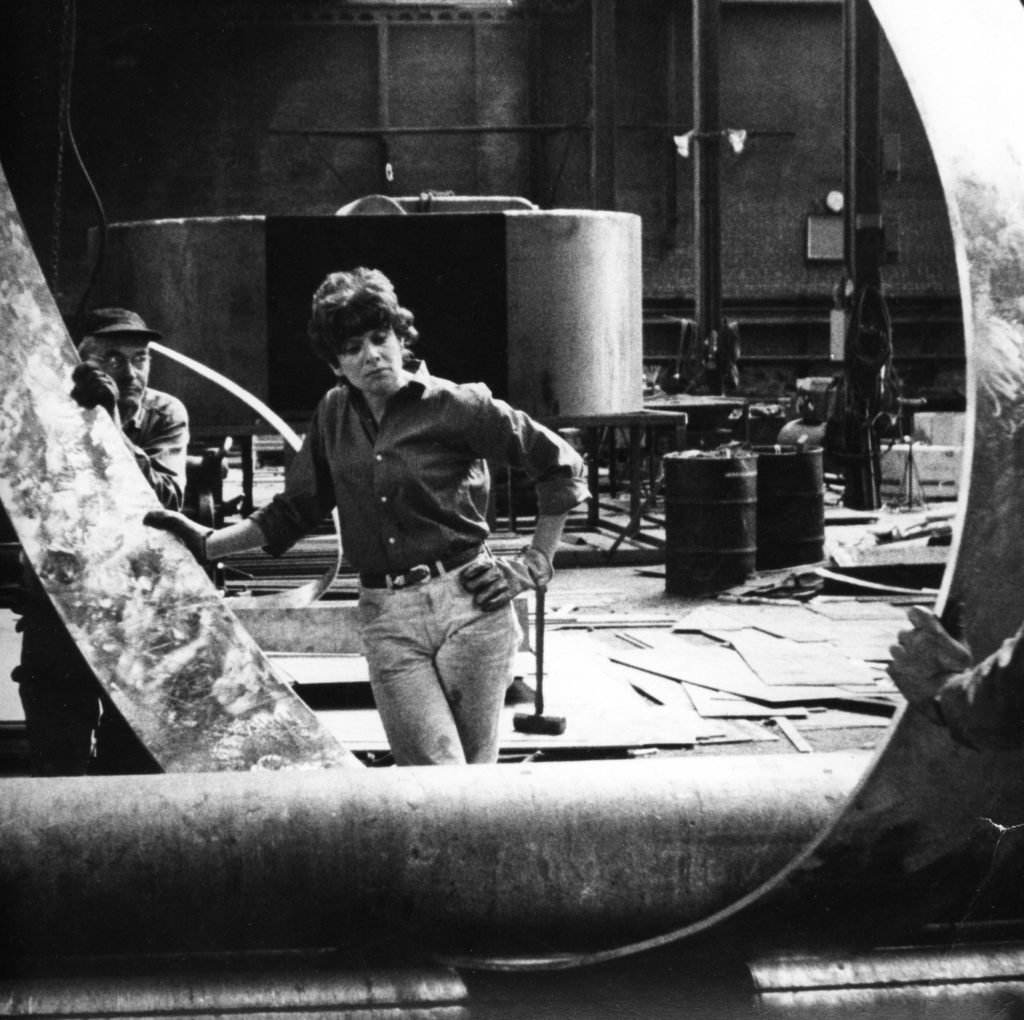

Beverly Pepper working at a foundry in Italy (circa 1960s). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

In the late 1940s, she moved to Paris and studied painting with André Lhote and Fernand Léger before meeting her future husband and moving to Rome, where he worked as the Mediterranean bureau chief for Newsweek.

As a respected painter throughout the 1950s, Pepper was included in high-profile shows across Europe, but she never felt comfortable with the medium.

“Paintings reach too small an audience,” she told the Smithsonian Archives of American Art in 2009. “It’s utterly ridiculous to try to make waves with a painting. You may wake a very small group of people.”

Beverly Pepper, My Circle.

Photo: courtesy Art in the Parks.

A trip to the temples of Angkor Wat with her daughter in 1960 inspired her to take up sculpture, a medium in which she had no formal training. Upon returning to Rome, she bought a jigsaw and other carpentry tools and carved up fallen trees in her garden.

Two years later, Pepper was invited to participate in an exhibition in Spoleto, Italy, alongside Alexander Calder, Henry Moore, and David Smith. She lied about being able to weld so she could work in the Italian steel plant sponsoring the show.

In the years that followed, Pepper became a master craftsman, known for shaping tons of metal into seemingly weightless forms. Among her best-known works are towering steel plinths such as the Manhattan Sentinels (1993–96), installed in New York, and The Todi Columns (1979) in her adopted Italian hometown.

She made polished steel structures that play with perception, such as a zig-zagging work in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, and sculptural interventions in the land, like Land Canal — Hillside (1971–75) in Dallas and Sol i Ombra Park (1987–92) in Barcelona.

Installation view of Beverly Pepper “Cor-Ten” at Marlborough Contemporary.

Until her last days, Pepper continued to work every day in the studio. Her works are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Barcelona Museum of Modern Art, the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, among many others.

Her sculptures, usually designed for public spaces, are permanently installed in cities throughout the world, including in New York, Dallas, and Assisi.

“My sculptural language has developed and grown for 60 years,” the artist told Artnet News last year on the occasion of a show at the Marlborough Contemporary gallery.

“Seeing, touching, and physical sensory engagement is the way into my sculpture; my intention is that the meaning of my work rests in experiencing it.”