People

Beyond ‘The Rose’: A New Monograph Shines a Light on Abstract Expressionist Jay DeFeo’s Unseen Photography

A new monograph highlights the artist's trove of photographs, many never before seen by the public.

A new monograph highlights the artist's trove of photographs, many never before seen by the public.

Karen Chernick

Jay DeFeo barely took any photos of her hefty one-ton painting, The Rose (1958-66), during the seven years she spent layering it with inches of impasto and chiseling it. She may have forever regretted that.

In fact, for the first half of the late Abstract Expressionist’s career she hardly ever recorded her paintings in progress. But around 1970, she began an intense—if brief—affair with photography, documenting herself, her surroundings, and her paintings in pictures that fuse formal prowess with poetic playfulness.

While some of these works are currently in museum collections (including the Centre Pompidou, J. Paul Getty Museum, and Whitney Museum of American Art), DeFeo has not been broadly known for her photography.

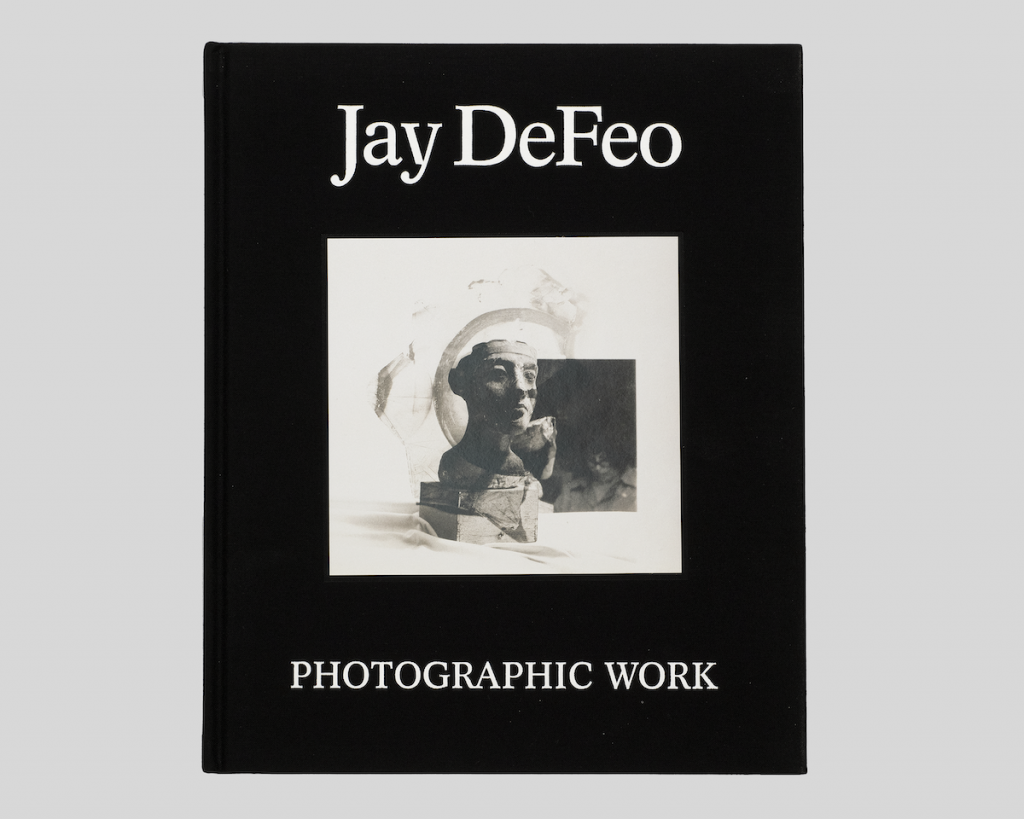

But a new monograph, Jay DeFeo: Photographic Work (DelMonico Books, 2023 which reproduces DeFeo’s photographs at their original (small) scale), stands to change that. The book’s publication coincided with a recent exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York, with over 70 photographs, photocollages, photocopies, and chemigrams—the largest-ever presentation of the artist’s photographic work.

Jay DeFeo: Photographic Work. © 2023 The Jay DeFeo

Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Much like singles on an album, her dignified and serious paintings are the ‘hits’ that carry her legacy,” writes the late artist’s friend Catherine Wagner in Jay DeFeo: Photographic Work. “But for those of us who had the good fortune to know Jay, her photographs and collages, the ‘B-sides,’ now play like watershed discoveries, full of experimentation and innovation for both new and seasoned DeFeo aficionados to delight in.”

Best known in the Bay area, where she lived for most of her life, DeFeo’s work has seen a reevaluation since her 2012 traveling retrospective organized by the Whitney and shown at SFMOMA. Most of this focus has been on her early paintings that culminated in The Rose (now in the Whitney’s permanent collection) and on works on paper made subsequently. Lesser known is the four-year phase that DeFeo called “the dropout years,” when she painted very little. It was then, after The Rose was extracted from her studio, that she moved from lively San Francisco to quieter Marin County and picked up a camera instead of her paintbox.

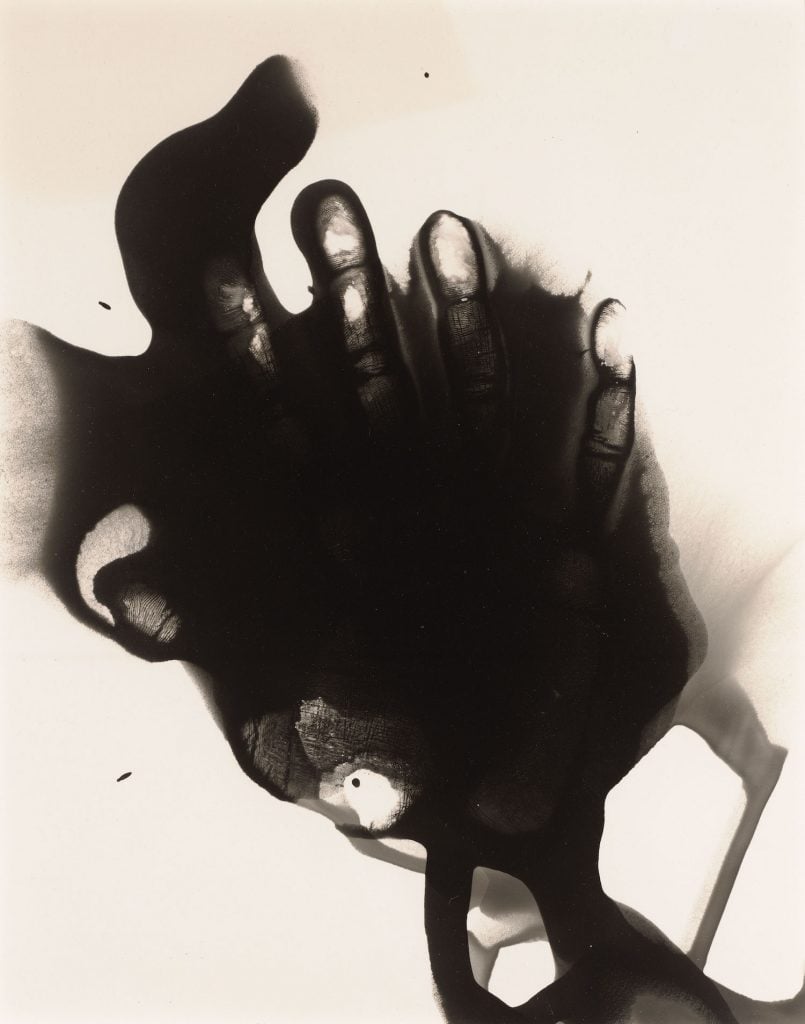

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (1973). © 2023 The Jay DeFeo

Foundation/Artists Rights Society

(ARS), New York.

“She took her photographic work very seriously,” said photography historian Corey Keller in a recent interview. “When she was preparing to meet a curator or preparing for an exhibition, she would really outline what she wanted them to look at. And almost invariably would say ‘look at the photographs, they are really important to me.’ Almost invariably, the curators would ignore them.” Indeed, DeFeo’s photos were only exhibited once in her lifetime, despite her best efforts.

Remarkably, DeFeo never formally studied photography but learned darkroom printing from her students at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), where she taught painting. SFAI had one of the oldest photography programs in the country, founded by Ansel Adams in 1945, and his classical influence seeped into DeFeo’s prints. “For someone who was not known for being very careful, she was really intentional about her photographic work,” Keller said. This was especially true of her photographic ‘portraits,’ pictures of beloved objects that show a mastery in composition, light exposure, and printing technique. (One such series was devoted to a discarded plaster cast once used by DeFeo’s dog, R. Mutt.)

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Salvador Dalí’s Birthday Party), May 11, 1973 (1973). © 2023 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

DeFeo soon became as experimental in her photos as she had been with her canvases, reversing negatives, cropping images, and sometimes not using negatives at all, but making chemigrams, exposing photographic papers to light and then pouring developer and fixer over them in painterly gestures. In a nod to the surreal quality of these prints, DeFeo titled a 1973 group of chemigrams Salvador Dalí’s Birthday Party. “She just wasn’t bound by any of the rules,” noted Keller. “If a medium had rules assigned to it, those went out the window.”

In the same vein, DeFeo also began creating enigmatic photo collages, cutting, tearing, and layering her own prints. She’d often explore a shape repeatedly—like an old telephone she kept in her studio or a chair she saw in a thrift store—cutting out the object’s silhouette to leave a void that she filled with other images. “It reminds me of Mad Libs, where you put these funny words in and you end up with kind of absurdist poetry,” Keller explained. “That’s how her collages work.”

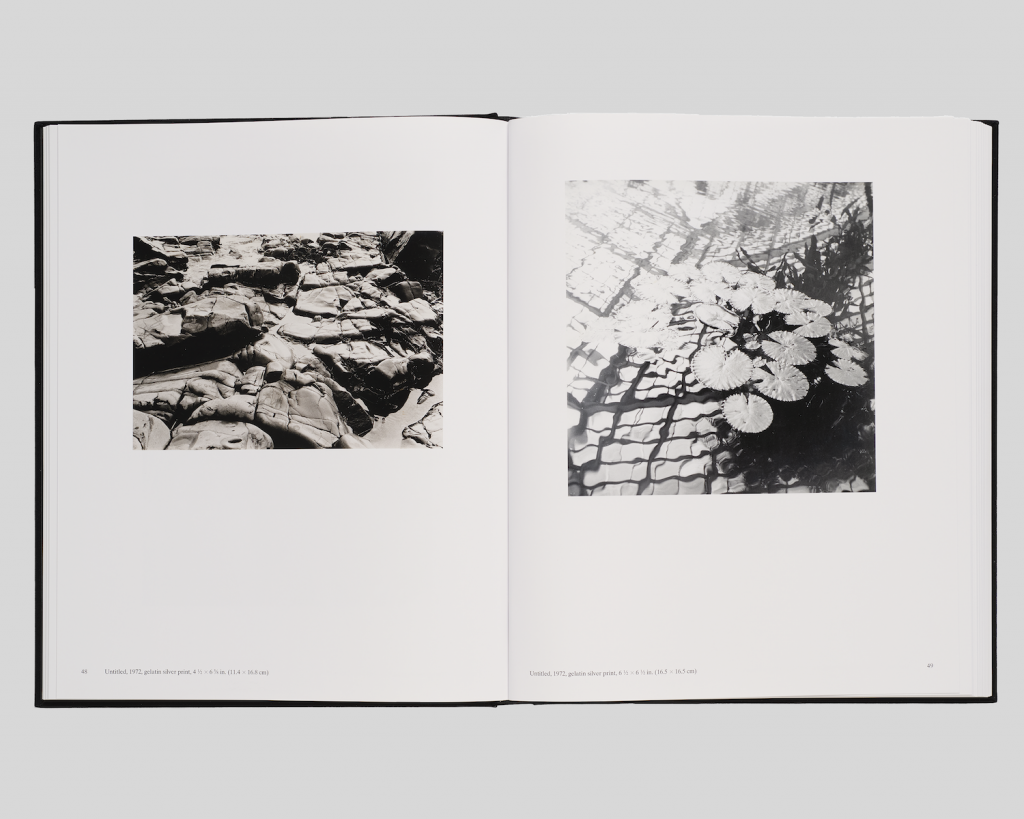

Images from Jay DeFeo: Photographic Work. © 2023 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

But it was in the late 70s that she began photographing paintings in progress—which some have speculated she regretted not doing for The Rose. As she told art historian Sidra Stich, these photos allowed her to take a step back and view “the strength of the real basic spatial statement … so that I don’t allow all the sensuousness of the paint to kind of seduce me into thinking I’ve got something structurally strong, when I don’t.”

DeFeo continued photographing into the 1980s, but the intensity slowly faded. Later in life, as she looked back on these works, DeFeo described her the process as having engaged with “photography for its own sake, which I just didn’t stay with long enough.”

Bruce Conner, THE WHITE ROSE (still) (1967). © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, © 2021 The Jay DeFeo Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

For now, her paintings still tend to be the draw for museums and collectors. “Market interest in DeFeo’s paintings and works on paper is, of course, more developed than that of the photographs, but this is largely due to this body of work being relatively little-known,” said Steve Henry, senior partner at Paula Cooper Gallery. Prices for her photographs reflect this, starting at around $20,000 against an auction record of $281,250 set in 2016 for an oil painting. An oil on paper sold at Sotheby’s New York in December 2022 for $94,500, exceeding its presale high estimate of $60,000.

Yet many believe that as her photographic work garners more notice, it will come to be as celebrated as The Rose. “Her career has been so overshadowed by the 2000-pound painting, the gorilla in the room. I think that there’s a prejudice, still, against the photographic output of a painter,” Keller said. “I would argue that I’m not sure if we can call her a painter anymore. I think she’s something more complex than that.”