People

How Bisa Butler Went From Being a High School Art Teacher to an In-Demand Quilter With a Show at the Art Institute of Chicago

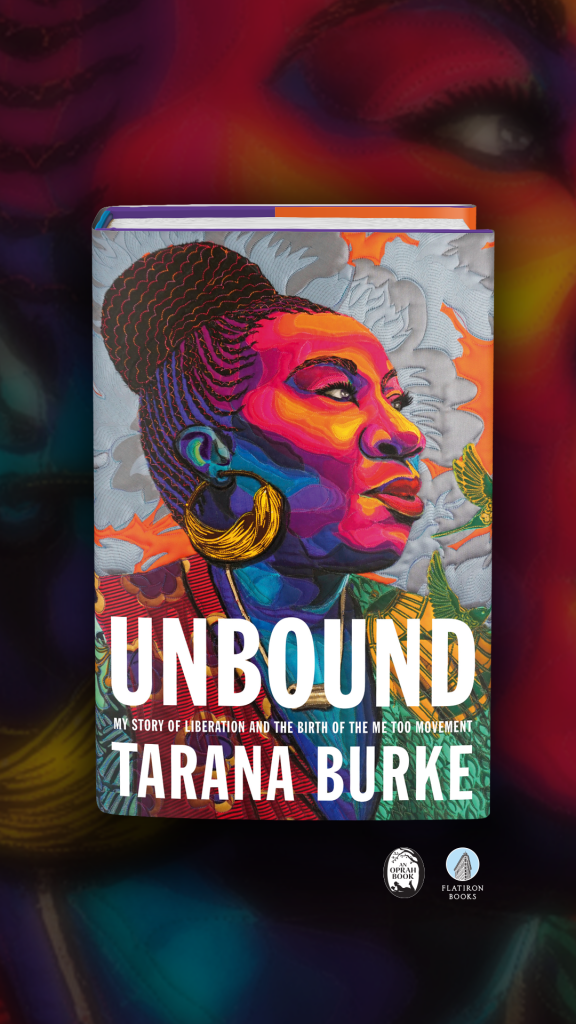

The artist recently designed the cover artwork for Tarana Burke's forthcoming memoir, "Unbound."

The artist recently designed the cover artwork for Tarana Burke's forthcoming memoir, "Unbound."

Katie White

Bisa Butler’s intricate portrait quilts are often based on found black-and-white photographs of Black people—some famous, some anonymous, some familial.

The New Jersey-based artist can spend thousands of hours translating these photographs into meticulously dazzling images. The process, Butler says, is akin to pulling her subjects out of the past and into life today; as she works, she wonders what these people were like. What did they sound like? What made them tick?

While Butler has been making quilts since the mid-’90s, the past year has proven a watershed moment for the 47-year-old artist. Though long delayed by the pandemic, an exhibition of her portraits opened at New York’s Katonah Museum in late 2020 and proved a critical hit. Another solo show—her most prominent outing to date—is on view now at the Art Institute of Chicago, featuring 20 of her luminous, multi-layered fabric portraits.

Butler, who is represented by New York’s Claire Oliver Gallery, has also recently been tapped to create portraits of influential figures such as Kenosha, Wisconsin, activist Porche Bennett-Bey. (Butler’s image of Bennett-Bey appeared on the cover of Time magazine when the activist was named the Guardian of the Year.)

Just last week, it was announced that Butler’s portrait of Me Too founder and activist Tarana Burke will appear on the cover of Burke’s forthcoming memoir, Unbound (available September 14).

We spoke with Butler about her whirlwind year, why finding success in her 40s has been a blessing, and how she recharges in stressful times.

Courtesy of the artist.

Your quilts are often based on old black-and-white photographs. How do you find these images? Do you search for particular figures, or do you just wait to see an image that draws you in?

Mostly, it’s a person who captures my attention. I follow different archivists on Instagram and sometimes a photo will catch me. You’ll notice in my works that people usually look directly out and at you. That kind of gaze stops me too, and I get thinking, “What is this person about?” Then I start looking around them for clues: what they’re wearing and what they might be doing. So at first, I won’t really know the context beyond the year the photograph was taken.

Say I find a photograph and the description or title is simply something like “Negro girls, Virginia.” I’ll just know the year, where they’re from, and that they’re Black. Then I have to fill in the blanks for the context. That makes it more interesting for me too, because then I’m like a detective trying to find out what was happening in Richmond, Virginia, in the ‘40s. What was the state of life for the average Black person? If these girls are in school, I know most likely that it’s a segregated school. What was happening in the country around that time? How did that impact this community?

It was interesting in the Katonah Museum exhibition to read about how you don’t necessarily feel the need to directly transpose a photograph into a quilted form, it’s more of an inspiration. Can you talk about that process?

There is a work called The Four Little Girls, a reference to the four little girls who were killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963. I had actually found a photograph with three little girls on a stoop, in what looked like church clothes. All I thought was, “Oh, this is so cute. Look how adorable these kids are.” I was working on it and then my husband walked by and he didn’t notice how many girls were he just said, “Oh, the four little girls.”

He made this connection that made that whole historical reference so much deeper—because these weren’t those little girls that were killed. I wound up adding the fourth girl. But it was revealing of our collective memory—when we see a group of little Black girls together in their church clothes, our mind goes to that bombing, which wound up being a catalyst for the Civil Rights movement.

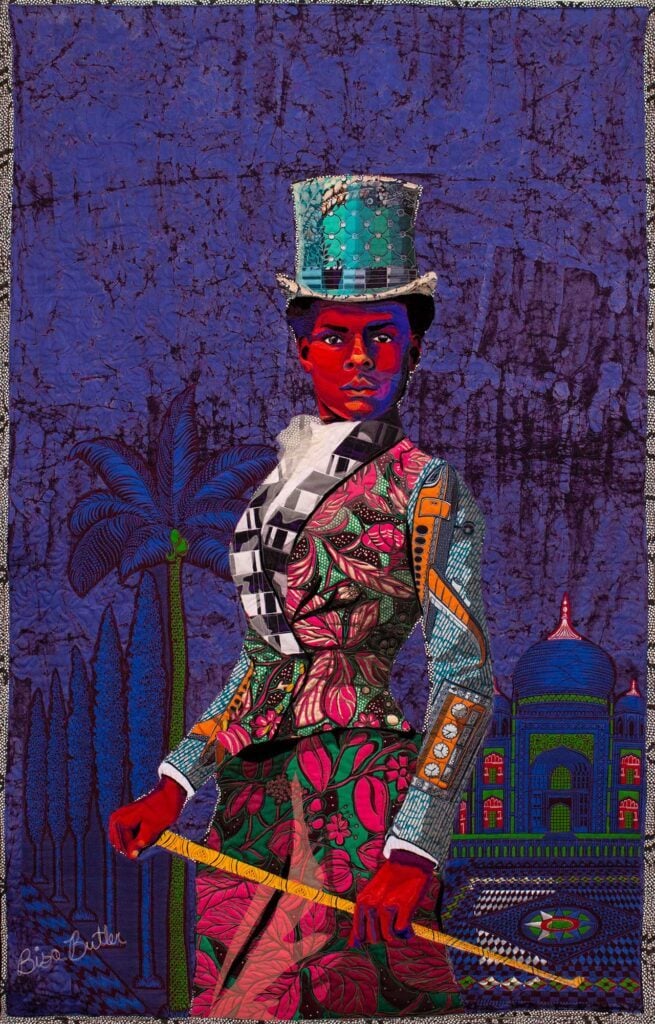

Bisa Butler, The Equestrian (2019). Photograph by Margaret Fox.

One of your works, The Equestrian, is a portrait of Selika Lazevski, the famous Black woman equestrian who lived in Belle Epoque-era Paris. The quilt is based on a photograph by Félix Nadar, but it’s so vibrant in color. It has a kind of Wizard of Oz feeling for me, coming into color. Do you ever feel that way, that you’re bringing these figures back to life?

That’s interesting that you even mentioned it. In the very first quilt work I ever made, I was trying to imagine what my grandfather looked like. My father’s father was from West Africa. My father’s in his 80s now and his father died in the 1950s from appendicitis. They didn’t have any photographs of him—he was living in rural Ghana and if there were photographs of him, they didn’t survive.

I had this desire to recapture him. I looked up men from Northern Ghana because there’s a distinct look to people from that area. They had migrated into the country from places like Mali, and were a desert tribe of people, not the Ashanti people we think of generally. So I started looking at photographs, and in making that work, I was trying to recapture my grandfather in color, and imagining what it would be like if I could talk to him. What are the things that he would have to say to me? What did his voice sound like? That sense of longing spreads to how I look at other photos, too. Who is this person I am looking at? I want to bring them back in a way.

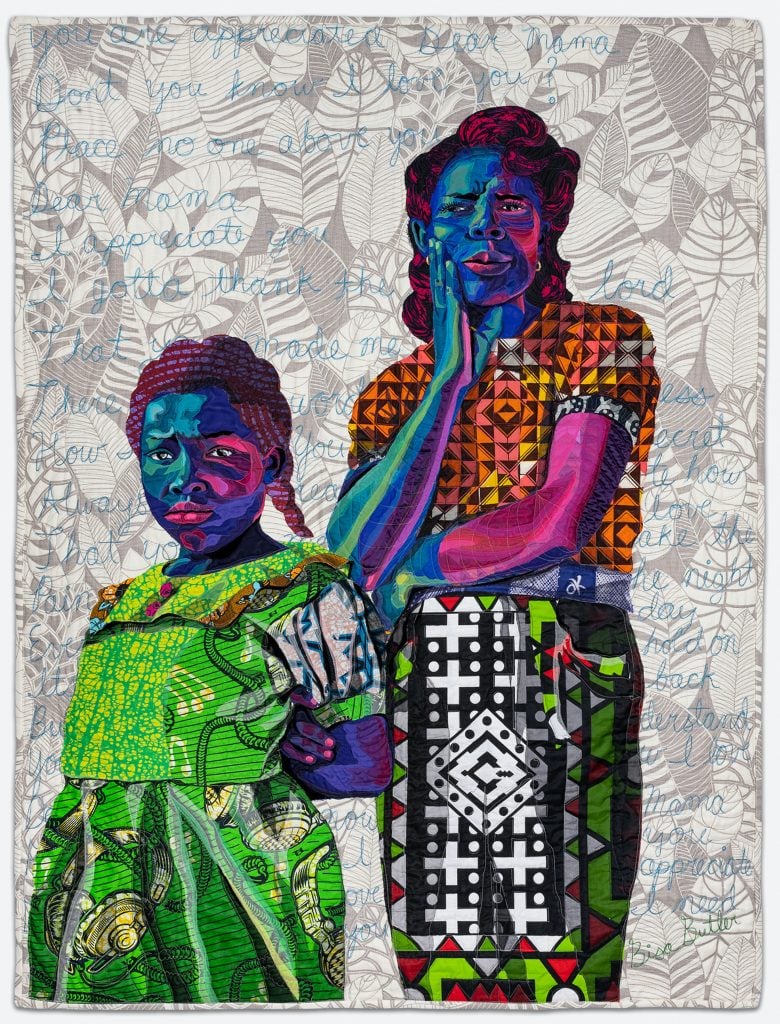

Bisa Butler, Dear Mama (2019). Collection of Scott and Cissy Wolfe. Photograph by Margaret Fox.

There are an incredible number of different types of fabric in each work. In these little itty bits of area, you have multiple types of fabrics layered in. Where do you find all these? Do they have any certain significance to you?

One of the best things about working on a wider national scale is that more people see what I’m doing, so I’m getting help finding fabrics. Before, all I had were my mother’s and my grandmother’s leftover fabrics because I couldn’t afford to buy new fabrics, and they had so many remnants that I didn’t need big pieces. I started out using mostly dressmaker’s fabrics. Traditional quilters would never be using silk and lace and chiffon all together, but those were what was available. My mother had bits of fabric from wool to gaberdine to tweeds and my mindset was, “What can I do with this?”

But that forced me to expand my definition of what a quilt could look like. My grandmother used a lot of vintage African fabrics. African fabrics only have a short run—companies will put them out for a month and then they retire that print and that’s it. One print had these squares on it and for whatever reason women in the marketplace saw it and they called it “billionaire.” It got really popular and so it became like a status symbol. If you were wearing that billionaire fabric, it meant that you bought it within a certain month. It is very cool because when people see it they say, “Oh, I know that fabric. I remember when billionaire came out.”

Do you have a least favorite part when you’re working on a new work? Is there some part that you’re dreading doing?

I don’t know why, but every time I start a new face, I’m always a little worried that I won’t get it. I kind of say a little prayer to myself like “Oh God, I hope I get this right.” Because if I don’t, then I have to scrap it and start all over again. I have like a bunch of half-done faces—a little catalog of them that I just had to put aside. I will just have to say, “Nope. I’ve been working on this thing for three days straight, 10 hours each time, and it’s not right. It’s actually getting worse.”

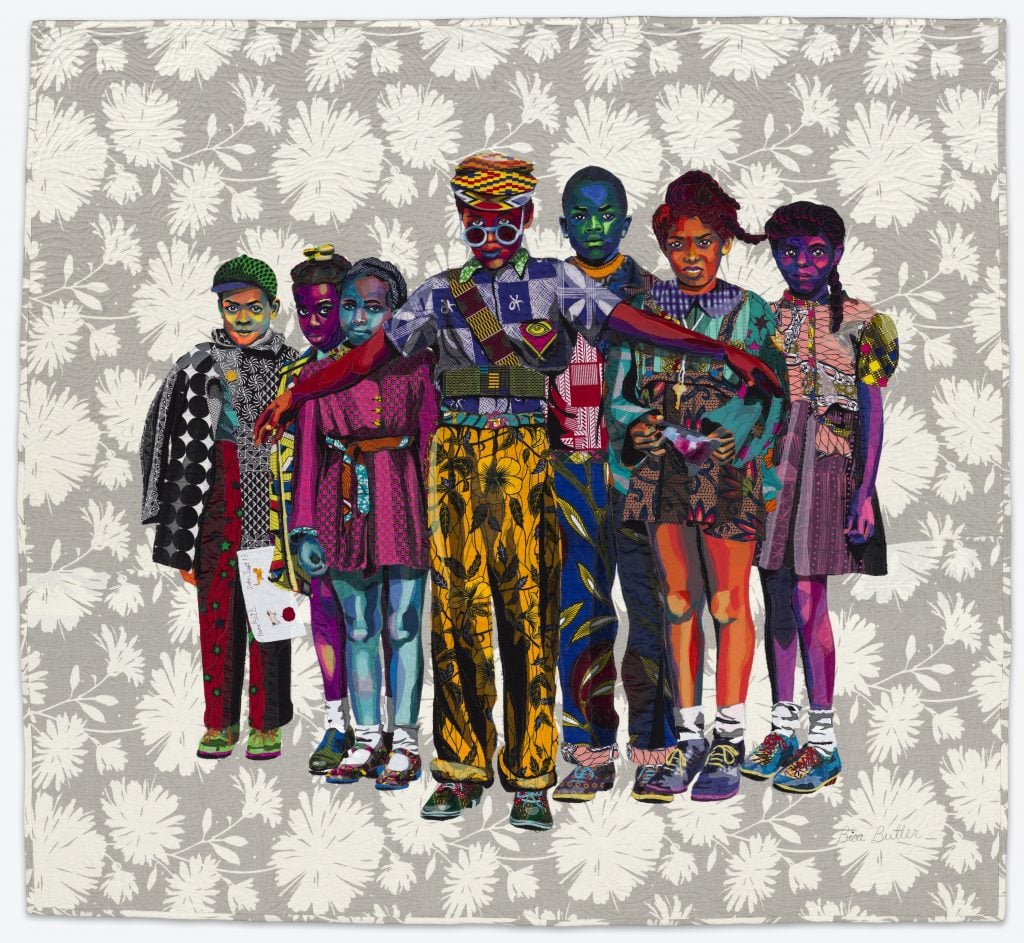

Bisa Butler, The Safety Patrol (2018). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, Cavigga Family Trust Fund, and the artist.

You were a high school art teacher for many years. Do you think that teaching had any effect on your work?

Oh, for sure. The influence of the kids helped a lot, being around their energy and their interests. I started doing these images of children, especially when I was getting ready to leave teaching and was feeling sad about it. I made some of my favorite pieces then, like The Safety Patrol and South Side, Sunday Morning. I had a student, this young girl Vivi, and her mom owns a yarn shop in town. She just came in with a big bag of fabric and was like, “Oh, I was just thinking about you, Ms. B.!”

The past year has been trying on a number of levels. How do you try to recharge?

I really love to read and lately, I’ve been really into Gua sha. It makes me feel so relaxed and helps with tension.

Recently, you’ve made portraits of some of the activists you admire, including Porche Bennett-Bey and Tarana Burke. But I wonder, who are some of the artists who inspire you?

I think about Elizabeth Catlett, Romare Bearden, Faith Ringgold, and Jacob Lawrence, who were educators for years and years. Elizabeth Catlett worked until she was 98. Aside from Jacob Lawrence, these artists worked well into their 40s before they were recognized. I feel a kinship because I wasn’t able to work on a national stage until recently.

Another artist I love is Alma Thomas. She graduated from Howard, too, and taught in the DC public schools until she was in her 60s. She went big time after she retired and became the first Black woman to have a show at the Whitney when she was in her 70s. She worked until she couldn’t. So if Alma could do it, there is no reason for me to sit around and act like I can’t.