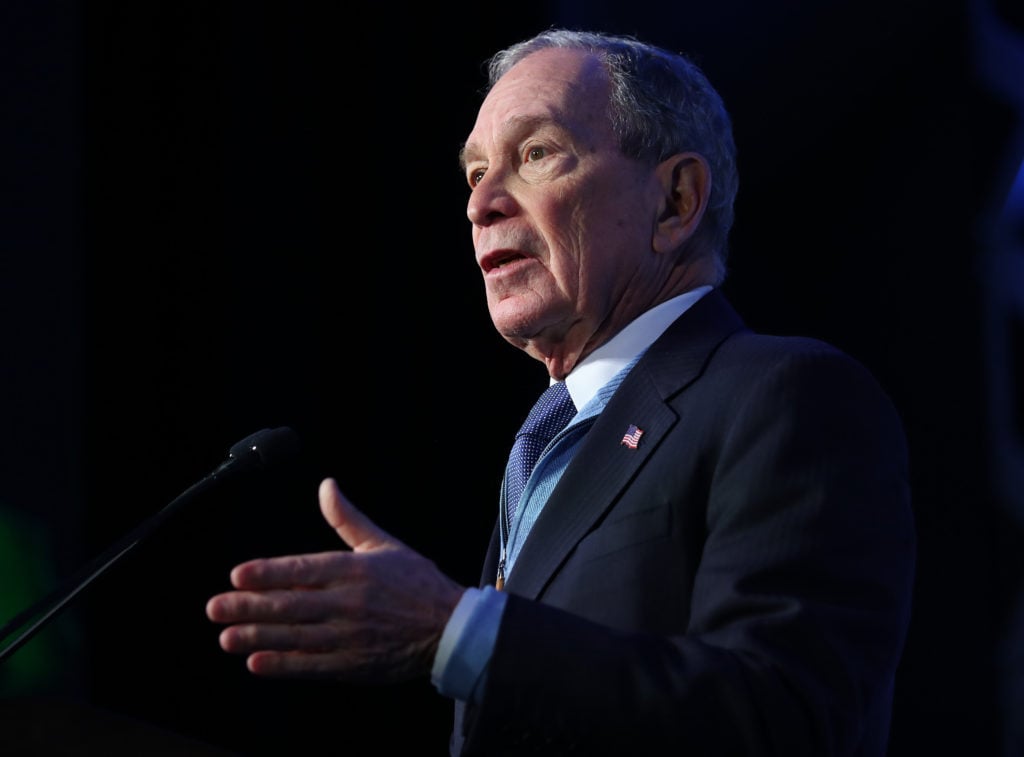

For decades, Michael Bloomberg has maintained his status as one of the biggest patrons of the arts alive. Not only has he given widely to museums in New York, the city he ruled over as mayor for three terms, but his second home of London has also been the beneficiary of major gifts. Since leaving office, Bloomberg has spent a fair amount of time in the world’s second-biggest art-market city, where he is the chairman of the board of the Serpentine Galleries, the Hyde Park institution overseen by artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist.

And while he’s very public about his gifts to institutions—and is a regular on the museum gala circuit—he is completely tight-lipped about what’s in his private collection. Bloomberg’s vast fortune—currently estimated at $59.6 billion—has allowed him to collect art at will, but he’s never been as public about his trophy hunting.

We know the names of artists who Bloomberg has greenlighted for public art projects in New York, such as Christo, whose Gates he successfully fought to bring to Central Park in 2005, allowing the artist to drape 23 miles of fabric through the middle of Manhattan. He also supported Ugo Rondinone’s stone statues in Rockefeller Center in 2012, and launched a Public Art Challenge in 2018 that would award millions of dollars to different cities for arts initiatives. Art permeates his media company as well: When the massive new London Bloomberg LP building opened in 2018, it included newly commissioned work by Cristina Iglesias, Olafur Eliasson, and Pae White.

But whose work does he hang on his own walls? Now that the former New York mayor is running for president and poised to win a significant number of delegates—and, though a long shot, could plausibly capture the nomination—we asked advisors, dealers, and others in the know what exactly is hanging up in Bloomberg’s houses… all 12 of them, in Manhattan, Westchester County, Vail, Florida, London, the Hamptons, and Bermuda.

From left, Julia Peyton-Jones, Chancellor George Osborne, Frances Osborne, Mayor of New York Michael Bloomberg, and Hans Ulrich Obrist attend a donors dinner hosted by Michael Bloomberg & Graydon Carter to celebrate the launch of the new Serpentine Sackler Gallery designed by Zaha Hadid on September 24, 2013 in London. Photo by David M. Benett/Getty Images.

A Social Animal

By the mid-1990s, Bloomberg was primarily known as the founder of Bloomberg LP, the multi-billion-dollar financial services company that sent Wall Street traders need-to-know info to Bloomberg-branded computer terminals. He had yet to set up his philanthropic efforts, and though he collected art a little bit, rarely did he step out on the art scene. Things began to shift in 1997, when he began to involve himself in the art world on two sides of the Atlantic.

That summer, Bloomberg joined the board of the Met, and by the fall, he was being courted to underwrite “The Warhol Look: Glamor, Style, Fashion,” a show that was set to open in November at the Whitney Museum of American Art, then on the Upper East Side, near his apartment. (The original backer, Gianni Versace, was gunned down in front of his South Beach home months earlier.) Bloomberg agreed, though he admitted he would not usually be the first person approached to back a show of work by Andy Warhol—he didn’t own a single work of art by the artist at the time.

“We probably would not have had very much in common,” Bloomberg said of Warhol in an interview with the New York Observer in 1997. “A lot of Warhol’s stuff I’m not sure that I like.”

A few years later, he told the New York Times, “Would I prefer to have Jasper Johns and de Kooning and Warhol stuff all around? I don’t know. That says less to me.”

So what was he collecting in his pre-mayoral years? Sources have said that, for the most part, he was buying work by artists from the Hudson River School, which includes Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church, as well as 19th-and 20th-century paintings, and porcelain vases. In the same interview with the Times, he mentioned that he was into buying Old Masters and Italian painters but not “that medieval religious stuff that is so serious and so overdone.”

Artist Christo, right, poses for a photograph with Mike Bloomberg as he unveils his first UK outdoor work on Serpentine Lake, with accompanying exhibition at at The Serpentine Gallery on June 18, 2018 in London. Photo by Tim P. Whitby/Tim P. Whitby/Getty Images for Serpentine Galleries.

But some signs pointed to what would later become an interest in more contemporary art. In addition to his involvements with the Met and the Whitney, he was also making inroads to the art world in London. In 1997, he started making trips to oversee Bloomberg LP’s headquarters over there and wanted to enter society across the pond. So he enlisted the social acumen of Julia Hobsbawm, a young public-relations pro with the upper crust on speed dial. She booked him dinners at hot-in-the-90s boites like Bluebird and filled them with leading cultural figures—and that’s how he met dealer Jay Jopling, who had just married the artist Sam Taylor-Wood, and that summer was showing new paintings by Ashley Bickerton.

That year also marked the beginning of Bloomberg’s long relationship with the Serpentine Galleries, which since the ’70s has been one of London’s more adventurous contemporary art spaces. Like he did with his business—and later the mayor’s race, and his bid to be president—Bloomberg courted directly and put his money where his mouth is.

When Julia Peyton-Jones, then serving as the director of the Serpentine, was invited to a dinner thrown by Bloomberg, she was intrigued by this newly out-and-about American billionaire, who had sat her directly next to him. Sensing an opportunity, she asked if he would consider donating to the institution, and he wrote a check for £250,000. He joined the board and, more than 20 years later, serves as its chairman.

“I found him absolutely hilarious and extremely endearing,” Peyton-Jones told New York magazine in 2002. “He was completely irreverent and talked about the arts in a very straightforward way.”

Mayor Mike Bloomberg at the National Arts Awards at Cipriani 42nd St., October 7, 2002. © Patrick McMullan.

Impulsing Buying Benglis

As for his own collection, it has long been overseen by the art advisor Nancy Rosen, who also served on a number of cultural councils and boards while Hizzoner was in office. Sources said that most of Bloomberg’s collecting happens directly through Rosen, though he personally attends art fairs such as The Winter Show and the ADAA’s Art Show, which both take place at the Park Avenue Armory. He was also an early supporter of Frieze New York, and as mayor played a major role in having the London fair’s first spin-off come to Randall’s Island.

“New York City has long been a global center for arts and culture, and in recent years, the number and size of local art fairs that attract New Yorkers and visitors from around the world has grown dramatically,” he said in a statement when the fair was announced.

(He’s also a longtime visitor to the original fair, writing in a column in the Evening Standard ahead of the 2018 edition, “If you’re in London pay Regent’s Park a visit. You may think some of it is brilliant and some it is, well, not so brilliant.”)

What does he buy at these fairs, if anything? A source close to the transaction said that Bloomberg bought a sculpture by Lynda Benglis from the Cheim & Read booth at Frieze New York a few years ago, snapping it up on impulse after just a few minutes of deliberating.

Though the source also said that while Bloomberg seemed somewhat interested in the Benglis work, it was not immediately clear from that he was a big fan of the artist prior to the purchase, adding that Rosen had been the guiding force behind the buy.

Rosen is also a frequent buyer at auction, and in May of 2018, she was bidding on Gilbert Stuart’s George Washington (Vaughan type) (1795) at the sale of works from the Rockefeller collection at Christie’s. Estimated at $1.2 million, the bidding immediately sailed past that, and when it hammered at $10 million—or $11.6 million with fees, a record for the artist—the winner was Rosen.

After the sale, ARTnews asked Rosen for her name, and she said “I have so many non-disclosure agreements that I would be in jail before I got home if I told you my name.” Her identity was later confirmed as Rosen by Josh Baer in his newsletter the Baer Faxt.

When reached for comment, Rosen said, “For many years my office has assisted a small number of individuals. We have consistently honored the privacy of our clients, and this would include Mayor Bloomberg.”

Artist Carrie Mae Weems (L) and honoree Michael Bloomberg attend the 15th annual Art for Life Gala hosted by Russell and Danny Simmons at Fairview Farms on July 26, 2014 in Water Mill, New York. Photo by Brian Ach/Getty Images for Art For Life Gala.

The First Collector President?

Bloomberg has been known to throw lavish soirees at his apartments around the globe, but social media is banned from these events, and those keen to be invited back aren’t spilling the goods on what’s on the walls. (A source who visited his campaign headquarters in midtown said there’s nothing hanging up apart from a cartoonish, vaguely street art-ish map of the US.) But in 2011, pictures of two townhouses appeared briefly on the website for the designer Jamie Drake, who has served as Bloomberg’s interior decorator for years. Experts eyeballed works that could have been 18th-century English portraits, as well as a portrait of Benjamin Franklin thought to be by Jean-Baptiste Greuze.

And the shots of the London pad on Cadogan Square in Knightsbridge revealed that Bloomberg’s tastes has evolved over the years. Despite his earlier antipathy toward Warhol, he now has a portrait of Marilyn Monroe by the artist. And though he said years ago that Jasper Johns “said less” to him, he now owns an extremely valuable Johns double flag work, as well as works from the artist’s numbers series. As for sculptures, he owns some by Roy Lichtenstein and Henry Moore.

(L-R) Robert Hurst, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, Brooke Garber Neidich, Neil Bluhm, Kate Levin, and Adam Weinberg attend the groundbreaking for the Whitney Museum’s new building on Gansevoort Street on May 24, 2011 in New York City. Photo by Ben Hider/WireImage.

The question remains whether Bloomberg will be able to continue to buy work if he’s in the White House next year—which, of course, is very much a hypothetical. Much hinges on his performance in Super Tuesday tomorrow, the first time he will appear on the ballot in a Democratic primary. (The campaign spokesperson Julie Wood did not respond to a request to interview the former mayor about his private art collection.)

But, after looking at his buying habits, it became clear that, though he has a fortune that could buy any artwork on the planet, he might just not have enough hunger for the art-collecting game to let it become more of a passion than his interests in politics or business.

“I don’t have any more wall space left and I just don’t have time,” Bloomberg told the New York Times in 2005. “I get home at 11, I am up to run at 5, out by 7. Who has time?”