Art World

Blueprint: Frank Gehry’s Dream House Really Pissed Off His Neighbors

Fellow residents initially considered his Santa Monica home to be an eyesore.

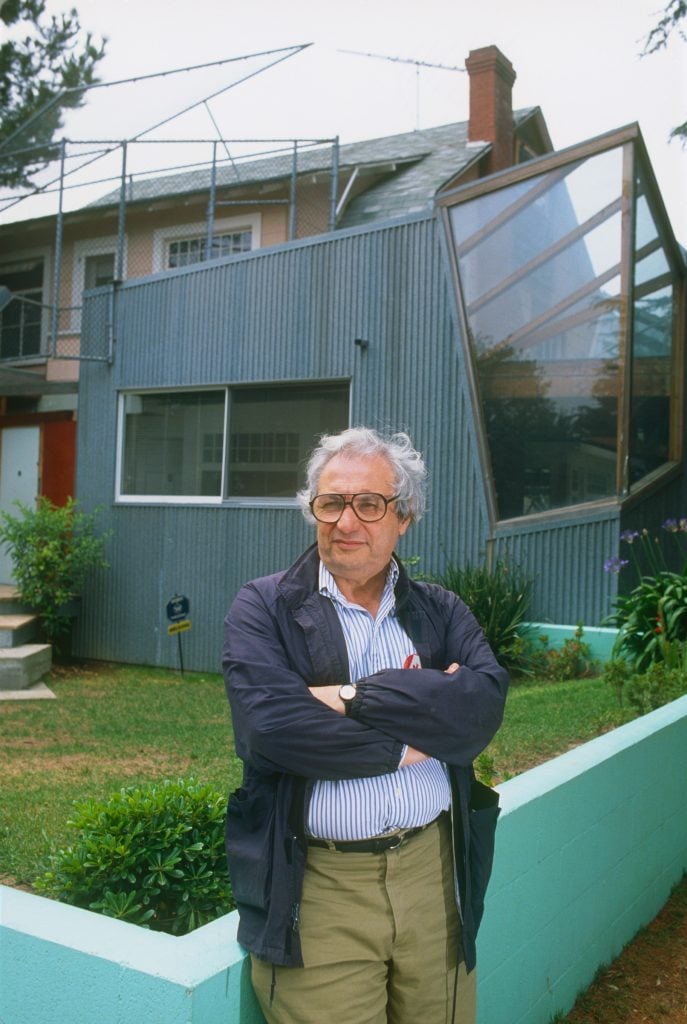

The Frank Gehry house on corner of Washington Ave. and 22nd St., Santa Monica. Photo: Ken Lubas / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

You’d think people would be excited when they hear a famous architect is designing a building in their neighborhood, but this wasn’t the response Frank Gehry received after he finished constructing his own dream home in Santa Monica, Los Angeles.

“The neighbors got really pissed off,” the 95-year-old architect recalled in a 2021 interview published in Dezeen. One of them, a lawyer, even came knocking on his door, informing him she was going to file a lawsuit with the city to try and take his building down.

The lawyer had her reasons, as the home—officially known as the “Frank and Berta Gehry Residence”—stuck out like a sore thumb in its typical, suburban surroundings. Its story begins in 1977, when the couple purchased a pink bungalow that had been built in 1920. Rather than tearing the entire thing down, Gehry decided he would build around it using cheap and readily available materials like glass, plywood, and corrugated metal—a key feature of his iconoclastic style.

Interior of American modern architect Frank Gehry’s house showing the dining area just off the kitchen, Santa Monica, California, January 1980. Photo: Susan Wood/Getty Images.

“From the inside,” Frank Gehry explained, “I was interested in looking up and out rather than sideways, because the neighborhood wasn’t thrilling in terms of architecture. But from the rooftop you could actually see the ocean, you could see the airport.” He also paid attention to the placement of the windows, putting them in locations where they’d play off streetlights, passing cars, and the shadows of the trees.

Contrary to what mythologizing accounts of Gehry’s life and work might have you believe, the construction of his Santa Monica home was first and foremost guided by necessity, not inspiration. “We had two little kids and not much money,” Gehry said, adding that the reconstruction cost him less than $50,000.

Interior of Canadian-American modern architect Frank Gehry’s house showing the kitchen, Santa Monica, California, January 1980. Photo: Susan Wood/Getty Images.

That’s not to say Gehry’s design was entirely random, even if it looked this way to some of his neighbors. Flaunting conventions, he used galvanized metal, while his liberal use of wood was influenced by his appreciation of traditional Japanese architecture.

The end result fits the description offered by the Pritzker Prize jury in their 1989 citation: “His sometimes controversial, but always arresting body of work has been variously described as iconoclastic, rambunctious, and impermanent, but the jury, in making this award, commends this restless spirit that has made his buildings a unique expression of contemporary society and its ambivalent values.”

A blog post on the architectural discussion forum Archinect may have put it more succinctly yet, writing, “Most of Gehry’s structures force a material to do what it is not meant to do.”

Exterior of Canadian-born American architect Frank Gehry’s house, showing the back steps, a corrugated iron wall, and a balcony enclosed by a chain link fence, Santa Monica, California, January 1980. Photo: Susan Wood/Getty Images.

Frank Gehry went on to spend the majority of his adult life in Santa Monica. Over time, his neighbors came around to his initially bewildering design. When another nearby resident came to complain about the construction, the architect pointed to the man’s trailer, which was made of many of the same, supposedly unappealing materials.

“He had to think about it,” Gehry recalled. “He didn’t quite get it, but he didn’t make trouble.”

As for the lawyer, she never succeeded in taking down Gehry’s home. On the contrary, the architect remembers how, one day, she ended up remodeling her own house in a similar style. Nowadays, the family does not have to deal with complaints so much as hordes of tourists and architecture students lining up on the front lawn. In the end, Frank Gehry surely had the last laugh.

Even the world’s most ambitious structure began with a humble plan. In Blueprint, we drill down to the foundations of dream homes and iconic buildings to explore how architects and designers brought them to life.