People

‘You Can’t Stay at the Side of a Genius For Too Long’: Bob Colacello on the Ups and Downs of Life in Andy Warhol’s Orbit

Colacello's photographs of VIP culture in the 1970s and '80s are on view at Thaddaeus Ropac in London.

Colacello's photographs of VIP culture in the 1970s and '80s are on view at Thaddaeus Ropac in London.

Naomi Rea

For someone who has partied with Mick Jagger, Cher, and a laundry list of other celebrities, artists, socialites, fashion designers, and the odd royal, Bob Colacello is surprisingly clean cut.

But you need to be put together if you are to become an important cultural historian, preserving pivotal moments in the zeitgeist for posterity—not that he set out to be one. As he put it: “it just happened.”

That nonchalant phrase is the title of the exhibition the now 76-year-old writer and longtime Andy Warhol collaborator has on view at Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in London, through July 29, which includes a trove of rare photographs taken during his 12-year tenure as editor of the legendary Interview magazine. As part of Warhol’s inner circle, Colacello was in the room for incredible moments in art history, and he documented the thick of the VIP culture of the late 1970s and early ’80s—from Studio 54 to the White House—on this pocket-sized Minox camera.

Colacello hailed from a conservative middle class background, studying international relations at Georgetown University, but he caught the artist’s eye while writing film reviews for the Village Voice. Eventually, he ended up parlaying his diplomacy skills not for political goodwill but to convince the ultra-wealthy to commission portraits from Andy Warhol, and steer Interview into the iconic publication it is known as today.

As one of a dwindling number of surviving members of Warhol’s tribe, he’s also a font of juicy details about its protagonist, not all of which made it into his memoir Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up.

We caught up with him about his journey from uptown to downtown, life in Warhol’s orbit, and the lowdown on who’s throwing the best art-world parties today.

Bob Colacello, Bianca Jagger, Halston‘s House, New York (1976). Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982.” © Bob Colacello. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

The show downstairs in the gallery, it’s an incredible roll call of famous names in cinema, music, art, politics. What was your first encounter with that ultra elite sphere and how did that come about?

Well, I did go to Georgetown, which was fairly elite. The King of Belgium’s nephew was in the dorm room next to mine, and I remember he had like 27 different colognes, and I was like, oh my God, we just have two colognes: Canoe and Old Spice…

But no, it was when I started working with Andy, who would always like to have a little entourage, so he would say, if I worked late, “Do you want to go to a party with me?” I remember the first night when they made me editor, we had dinner with Peter Beard and his wife then, Minnie Cushing. We went to the Algonquin Hotel with Peter Beard’s rich uncle, Jerome Hill, who was an elderly gentleman but he was an heir to the Northern Pacific Railroad fortune, like one of the robber baron scions. And he was an early investor in Interview, so Andy said, “Oh, you should meet the owner.”

And there was Sylvia Miles, the actress, and Minnie Cushing—Minnie Beard—arrived with a snake in her straw basket, and Peter was kind of a madman. And I was getting a little nervous and they were suggesting, “Let’s have a night cap up in Jerome’s suite,” and I really was like, “I think I’ve had enough for one night.” Sylvia saved me and said, “Oh, do you need a ride home? Where do you live? I can drop you.”

But very quickly, it was like: one night Mick Jagger’s 30th birthday party on the St Regis Roof given by Ahmet and Mica Ertegun, and I’d pick up Andy at his house and then we’d go and pick up Truman Capote and Lee Radziwill. And we’d come to Paris and stay at the Crillon at first before Andy got an apartment, and it would be again: a lunch at Marie-Hélène de Rothschild’s Hotel Lambert, then dinner at Sao Schlumberger’s extravagant house.

And what was Andy working on at the time?

Andy was basically doing society portraits at that time, that was the bread and butter. After being shot in ’68, he was too weak to make his own movies anymore—so Paul Morrissey took over—but also to do big series of paintings. I think he was psychologically tired from being shot close up three times and then going through five hours of operations with five surgeons on every vital organ except his heart.

So it wasn’t until ’72 that he started painting the “Mao” series. And the portrait commissions required going out there and socializing with the kind of people who have commissioned portraits, meaning rich people. So the focus was on that a lot and it was very international. Andy’s, I guess, biggest markets were Switzerland and Germany and Italy.

But we’d come to London and we’d go have tea with David Hockney, who is so sweet. He said to me as we were leaving, “Listen, I didn’t really get a chance to get to know you because you were with the whole group. If you’d like, come back tomorrow for tea and we can chat,” which was so nice. And again, I was 22, 23 years old and, this was David Hockney!

But people are people, and one of the things Andy liked about me was he said I could talk to anyone. I don’t know what it is about me but maybe I’m pretty open with people so they’re pretty open with me.

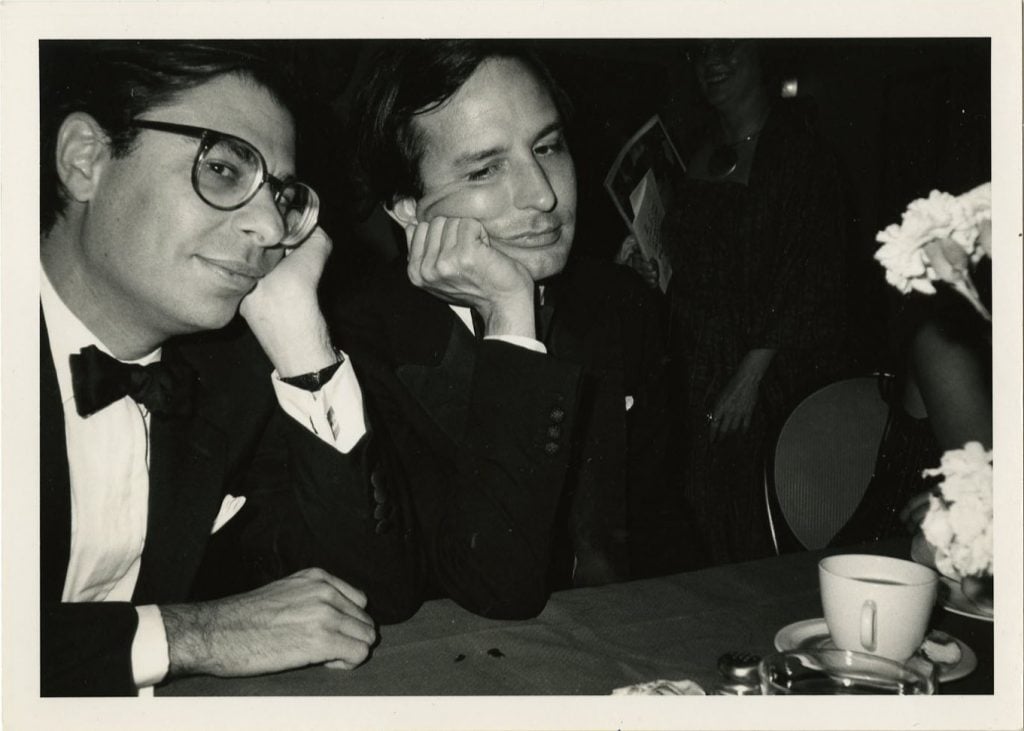

Bob Colacello, Bob Colacello and Fred Hughes (c. 1980). Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982.” © Bob Colacello. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

Did you share Andy’s deference for celebrity?

No, it wasn’t a deference. I mean if I met the Pope, there’d be a deference… No, first of all, I wasn’t really into celebrities. I went to the School of Foreign Service—my hobbies were maps, globes. I loved politics, I was reading the New York Times every day since I was about nine years old, so I was a little more impressed to meet Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan.

But it seemed to me quite quickly that these fancy Parisian ladies at lunch reminded me so much of my grandmother from Naples, and my sister, my Aunt Janny in Brooklyn sitting around the kitchen table and having lunch and gossiping about whatever lady friend wasn’t there that day. And I would say that to Andy and he would go, “Oh gee, oh gee, oh, you’re so smart, oh, really?” I don’t know, it’s not like I wasn’t impressed and I wasn’t a bit nervous in some of these situations, and I didn’t start drinking vodka on the rocks for the first time in my life. At Georgetown, the ‘60s was more about pot and LSD. In the ‘70s, Andy would be like, “Oh, you can’t smoke pot, that’s so hippie.”

You’ve spent a lot of time on the other end of the tape recorder. What was the most challenging interview that you ever did?

Oh, it was for Vanity Fair and I would say it was Balthus, the French artist who insisted on being called Count Klossowski, and when I told him I worked with Andy Warhol for 13 years, he said, “How unfortunate.” He asked me if I’d read Delacroix’s journals, and I was like, “Erm, Count, I’m afraid I haven’t,” and he was quickly learning that I’m not much of an intellectual. He didn’t say anything.

We went to see him, Bruce Weber [the American photographer] and I, every day for five days in Gstaad after lunch. Two days later he says, “You know, Mr. Colacello, there’s something I’ve been meaning to tell you since our first day. You said you weren’t an intellectual. I’m afraid you think I’m an intellectual. I don’t like the intellectuals, they put a veil between the mind and the heart.” I thought: pull quote!

The first couple of times I met Mick Jagger, I was intimidated just because I used to do Mick Jagger imitations at Georgetown parties. People who are really talented and really accomplished, I find for the most part don’t have to play the star all the time. They know how to make non-stars comfortable. But then there are some others that are pretentious and those… I could never be bothered to win over somebody. I always felt like, well, if they don’t like me, I have a right not to like them. But I have a way with people. I did study diplomacy at Georgetown…

Andy Warhol, Piss Painting. Photo: Eva Herzog, courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

We walked past an early Warhol “Piss” painting downstairs, and there’s actually an enormous one in the gallery just below us as well. I wanted to ask you—did you ever help him in that creative process?

No, I never did urinate on a canvas for Andy. No, the Factory that we moved into in 1974, 860 Broadway, where we stayed all the time I was there, was huge. It went from 17th Street to 18th Street, it was a block long, and Andy’s studio was way in the back. So, generally speaking, you left Andy alone when he was painting. I’d only go back there if there was some important phone call that involved a decision that only he could make, like the price of a painting or something.

But Victor Hugo, who was the boyfriend and window dresser and just kind of crazy man for Halston, he was more involved in bringing guys to piss for the “Piss” paintings which, when they were shown in the gallery, I forget which gallery showed them first, but their name was changed to the “Oxidation Paintings,” a little more discreet.

Was there a selection process for the people who were invited to “contribute”?

No—well, Victor Hugo would bring kind of hustlers actually, but, like, Ronnie Cutrone, our assistant would be one of the participants, and Rupert Smith, another artist who did all the prints. They were experimenting with if they took a lot of vitamin C did the copper paint, did it make the oxidation process more green or less green or more brown …

By vitamin C, you mean vitamins actually?

Yes, I do mean vitamins. If changing their diet in some way might change the color of the oxidizing process. I was not that involved in that series. You didn’t really get that involved in Andy’s actual process of painting. It was more in bouncing ideas off all of us, but he bounced ideas off everyone he met. Then it was more about selling the art, he turned us all into little art dealers.

Someone told me that the “Piss” paintings took their inspiration from Jackson Pollock, do you know if that is true?

Wasn’t Pollock supposed to have pissed on his paintings?

Yes, bound for collectors of whom he wasn’t really fond.

Yes, well, there’s a Pasolini movie called Theorem starring Silvana Mangano and Terence Stamp, and it’s about a rich Italian family who were, one-by-one, seduced by this good looking Englishman or intruder. And the son of the family is a painter, and there’s a scene where he’s pissing on his canvas, so I guess that was a reference to Pollock too. But I wasn’t there when he did it, so I don’t know.

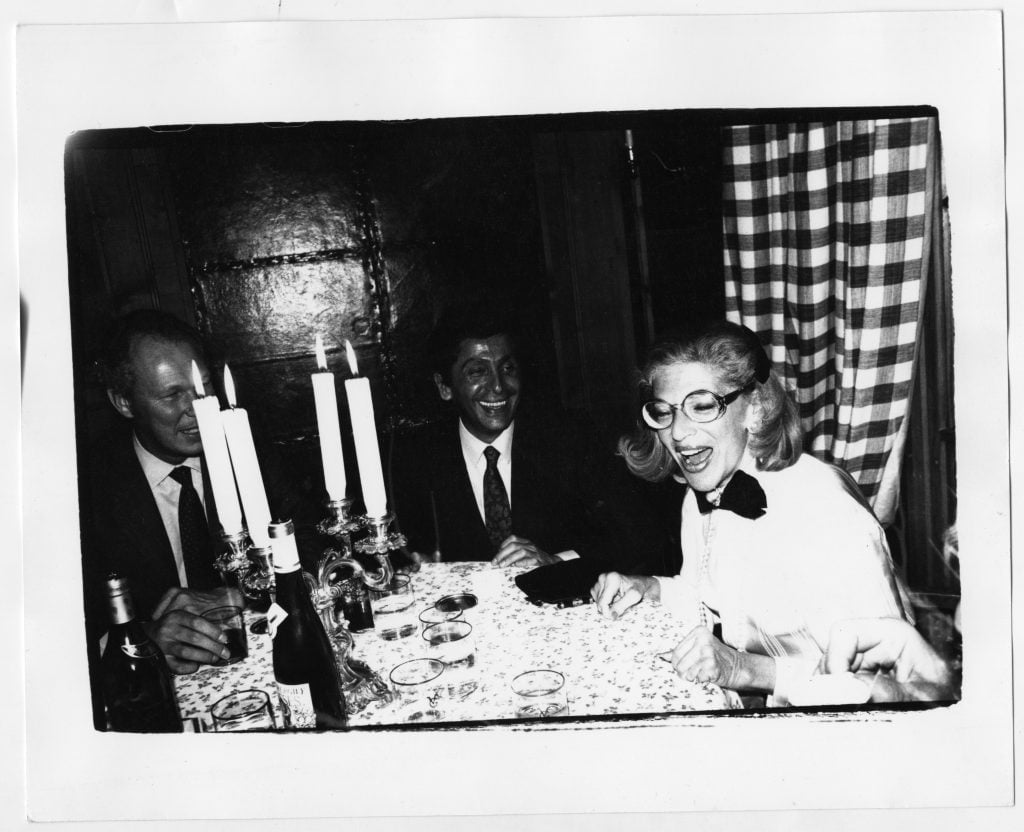

Bob Colacello, Prince Victor Emmanuel II, Valentino, Baroness Marie-Hélène de Rothschild, Gstaad (1980). Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982.” © Bob Colacello. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

When you were going to these parties and events with Andy, you’re selling the work as well as what, helping him document the scene? Did you have a set of instructions?

Well, we went to certain parties and we saw certain people who we thought could have their portraits done, you know, could afford it or would want it. And yes, you would weave it into the conversation, they’d say, “What’s Andy been working on?” Or, “Andy, what have you been up to?” And he would say, “Oh, Bob, what have I been up to?” And I’d say, “Well, we just did the portrait of Marella Agnelli for example,” and then they’d say, “Oh, Marella had her portrait done?” So it was that kind of selling.

In terms of helping him to record things, Andy did tape record everywhere he went. In restaurants they were so noisy, I don’t even know if you can understand the tapes. But the next day he would dictate his diary to Pat Hackett and I would dictate mine to her too. They were separate entities but we were both doing it to keep track of expenses for the IRS because Andy had been audited in 1972 and they caught him because he was taking off art deco furniture as props for sets for movies he wasn’t making. So we had to really document every taxicab.

What happened, did he get fined?

Yes, he got fined, you pay penalties and interest. It probably happened because Nixon was using the IRS to go after political enemies. And in 1972, Andy, who was a Democrat but who liked to avoid politics or any causes other than his own, was kind of pressured by Jackie Onassis and Lee Radziwill to do a poster for the [George] McGovern campaign. What he did was that famous head of Nixon, like in orange and greens looking really evil, and then it just said, “Vote McGovern” in the corner. He did 1,000 of those at $250 each, so that was a donation of $250,000, which in those days was really a lot, still is. And he went to the top of Nixon donors, and that came to the attention of the president, and next thing Andy knew he was being audited every year.

It sounds very conspiratorial.

Yes—again, you can’t prove it, and no one’s ever come up with a memo, but Nixon did have an enemies list and Andy was on the enemies list. But Andy was fascinated by Nixon and when Watergate broke and it came out that Nixon was tape recording everything, he became even more fascinated. And we would make a joke like Andy was Nixon and Fred Hughes and I were Ehrlichman and Haldeman, and Pat Hackett was Rosemary Woods. When she was typing up Andy’s tapes with the foot pedal, we’d say, “Pat, where are the missing 18 minutes?”

Also, Andy’s accountant and Andy’s lawyer called and said, “Andy, you don’t tape record phone calls with me, do you?” and Andy’s like, “Oh, no, no, no,” but he probably was. John Richardson called Andy the recording angel … If Andy could, he would have interviewed everybody, like he would turn this interview into an interview with you. He was curious about everybody and it was like he wanted to try to figure out what made humans work. He wasn’t really that good at interpersonal relationships.

Some people think he had Asperger’s in retrospect but, I don’t know, he was always trying to figure out what motivated people and why they did things, what they were interested in, what they thought was important. And it was a very democratic process, he would chat up everybody to the point of asking an elevator man what he should paint.

Installation view. Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982.” © Bob Colacello. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

Because you paid such close attention to documenting everything, I suppose there are not a whole load of excuses for overly fictionalized accounts of Andy’s life. What did you think of the Netflix documentary series The Andy Warhol Diaries?

Well, I think it was distorted in a sense. First of all, the artificial intelligence voice was very, very annoying and the opposite of Andy’s way of talking. Andy was singsong, that was very flat, and then there was this fake Warhol ghost who was toddling around his townhouse which is opulently overdecorated. I mean all that was totally inaccurate, Andy’s house was very stately and almost like the White House, in the federal-era period anyway.

But more to the point, today everything has to be through a lens. It has to be through a gay lens or a feminist lens or Black lens or Hispanic lens, and that was very much through a gay lens. Darkly. And Andy, of course he was gay, but in the interviews when he was asked that, he would say, “Oh, just look at my movies.” He didn’t like to declare himself or commit himself in any way, which I think artists in general can be that way because they don’t like to over-interpret their work, they don’t like to explain it. They’ll let others do that down the road.

I can remember it feeling depressing, on the one hand, I know many of my younger friends especially who didn’t know that much about Andy felt they learnt a lot. And I think the way each decade was set with these montages of the bigger cultural picture was really well done, and they had a huge budget.

But overall, I didn’t really like it even though I was in it, for what seems like more than anybody else in terms of living people. And for the first time in my life, I was stopped on the street by people saying, “Oh, I saw you in the Netflix documentary.”

Then I met Brian Murphy at a party, and he told me 80 million people had seen that documentary, and that was only a month after it streamed. But unlike Andy, my goal has never been to become famous. It’s always been to do what I want to do and write what I want to write. I saw too many famous people close up who were so miserable, starting with Andy in a way. I think fame happens. I called this show and the Paris show and my book “It Just Happened,” because my life has just happened.

I was brought up to seize opportunity when it comes along but never to be pushy, never to be aggressive, and I just found things happen if you wait for things to happen. I see some of the people who are always manipulating, trying to get to the right place at the right time, and it’s exhausting just watching them.

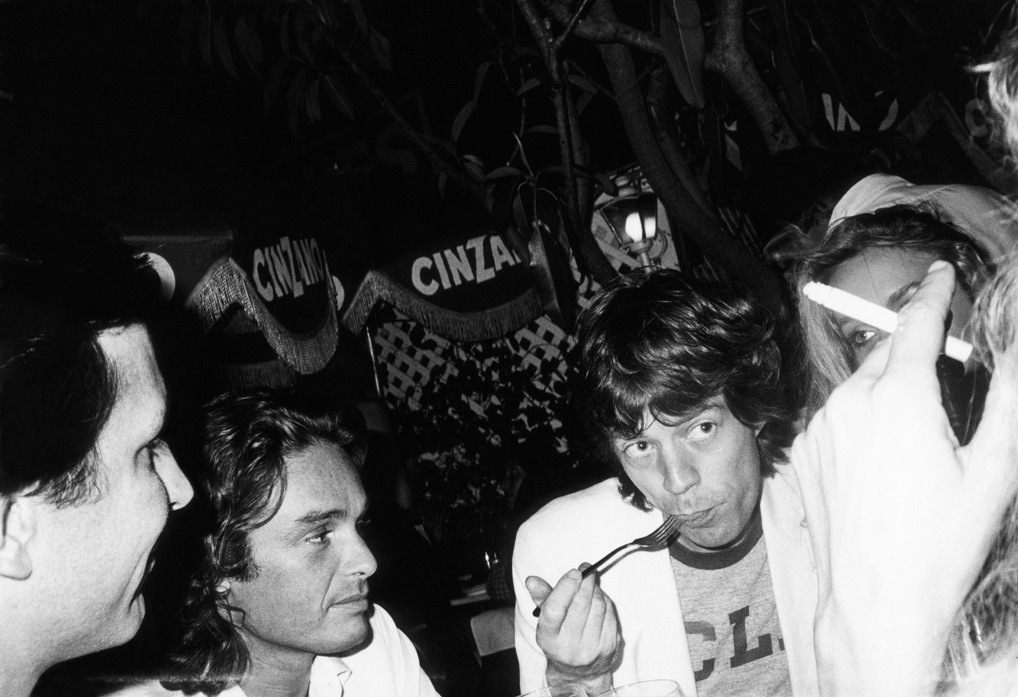

Bob Colacello, Fred Hughes, Patrice Calmettes, Mick Jagger, and Jerry Hall, Cafe Mustache, West Hollywood (1978). Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982.” © Bob Colacello. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

You stopped working with Andy at Interview magazine in the ‘80s, what happened?

Well, there were several things. One was, with Pat Hackett, I basically wrote Andy’s philosophy book in ’75. In ’79 we decided to do a book of Andy’s photos except 20 per cent of the photographs were actually mine. And I wrote the text in Andy’s voice. There was a lunch for Andy at the Corcoran Museum in Washington and the director said, “Andy Warhol is not only a great filmmaker and a great artist but we learn that he’s a great writer.” And I’m thinking, I wrote every word of that book.

Then Andy was constantly telling me that his new boyfriend John Gould thought we should put this person on the cover, and thought we should do this with it. I’m like, now he’s got all these diamond bracelets and necklaces, the next thing he’ll want is Interview magazine, and I thought: I don’t need this kind of insecurity.

And I’ve made the magazine successful, it’s profitable, everybody’s reading it. And Andy got jealous also that the press started writing about me as the editor of Interview. Then it didn’t help that Nancy Reagan decided she liked me the first time I met her and started calling. It would be “The White House calling for Bob,” not for Andy. Andy I don’t think liked that I was establishing an identity on my own rather than being one of his “kids” as he called us.

Also the thing was that John Gutfreund who was the chairman of Salomon Brothers, kind of Wall Street at the time, had told me that he could raise $10 million overnight to expand Interview. But he said, “Whoever invests would want to know you’re not leaving, and Andy would have to give you a little piece of equity.”

When I proposed that to Andy thinking he’d be thrilled—$10 million was like $100 million today—he was like, “Who do you think you are? It’s my magazine. You’re flying around in these private jets with these rich people stoned to your head.” And I’m like, “Andy, I’m flying around with rich people on their private jets selling your art. I’ve rather just be editor of Interview and not have to be art dealing. OK?”

So it just was time. I was 35 years old, I started there when I was 22. You can’t stay at the side of a genius—and I always thought Andy was a genius and I still do—for too long, you have nothing left for yourself. Both Fran Lebowitz and Robert Mapplethorpe always kept a distance with Andy. He said, “Why don’t they talk around me?” And Fran told me, “I don’t talk around Andy because the next thing I know my humor will be Andy Warhol’s humor.” She said, “You’ve given away too much, Bob.” So it was time to go.

But then there was a short period where I really was not into seeing Andy much, but we had a lot of the same friends. I went to Vanity Fair, I had my own thing going.

Installation view. Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982.” © Bob Colacello. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

How did you move to Vanity Fair, how did that door open for you?

Well, Vanity Fair was just in formation then, they didn’t really publish the first issue until ’74. But the one thing I did do when I realized I’ve got to get out of here was I took Mort Janklow, who was a prominent literally agent, as my agent, and he said, “Let me try to negotiate a better deal for you with Fred Hughes,” Andy’s manager. But he came back to me and said, “There’s no way Andy’s going to give you part of Interview, there’s no way you’re going to get what you want. So I think you should pursue other avenues.”

I knew S.I. Newhouse a little, but again with Andy I met everyone. I knew Alexander Liberman who was the editorial director of Condé Nast, and Leo Lerman who was the feature editor in Vogue who then they brought over to Vanity Fair, and it was Leo Lerman who actually signed me up but then he was kicked upstairs and Tina Brown came in a day later after I signed a contract. And she called me, she had just come to New York and said, “I really want to have breakfast with you because I really admire what you do with Interview and the mix and all of that. “

However long Tina was there, I had a great time with her, and then a great time with Graydon Carter, altogether 35 years.

What’s happening with Interview now?

Interview is owned by Peter Brandt or his daughter Kelly actually is the owner. I think it’s looking really good. They’ve got a good editorial team. Under Ingrid Sischy, it really was quite strong. I think it had a lot of ups and downs. Peter bought Sandy Brandt’s 50 per cent back, and I think it’s on a really good path now.

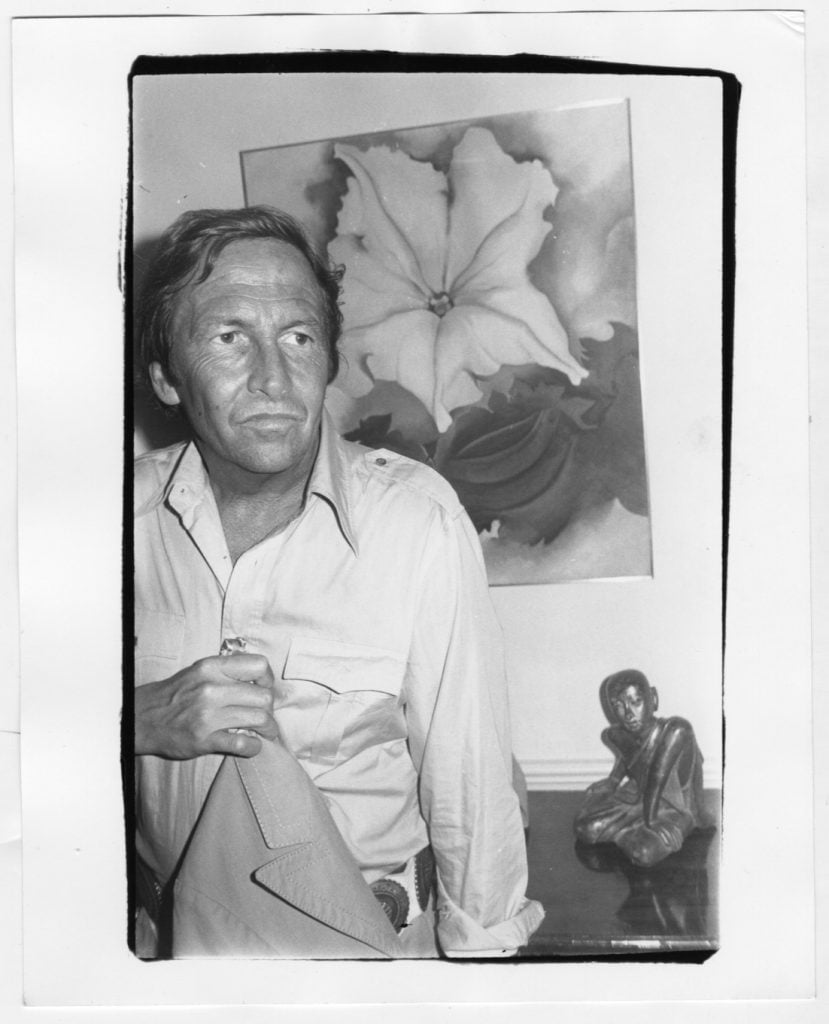

Bob Colacello, Robert Rauschenberg, Washington D.C. (1977). Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982.” © Bob Colacello. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery.

I read your interview with Ariana Papademetropoulos. She’s cool.

I love Ariana. I love her work and I love her as a person. She’s soulful, she doesn’t feel like she has to dress like an artist or have to get a lot of tattoos…She’s kind of proper but she’s very funny, and she’s so talented. The combination of the hyperrealist technique with these fantasy scenarios I think really is special, so I agreed to interview her.

Are you spending much time in the art scene in New York?

Yes, a lot of time because I work with Vito Schnabel and I work with Peter Marino. I’m associate director of Peter Marino’s Art Foundation in Southampton, and for 10 years now I’ve been Vito’s senior advisor, which means I’m old and Vito doesn’t listen to me, but we have fun.

I’m really lucky because I’m plugged in to all the younger artists, Rashid Johnson’s a good friend, Ariana’s a great new friend, on and on and on. Then Francesco Clemente joined Vito’s gallery, we know each other since the ‘80s. I’m very lucky because everything I do is with friends and so it doesn’t feel like work.

What do you feel has changed about the scene?

In 1970, there were like 10 prominent artists: Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, one woman, Louise Nevelson who went out of fashion, and now is coming back. There were four or five contemporary galleries: Castelli’s, Sonnabend, Holly Solomon, Paula Cooper… And there were a handful of collectors: S.I. Newhouse and Peter Brandt, who was collecting very young, Keith Barish, Sol Steinberg…

Over the years it’s gone from a village that has exploded into a megopolis. And I think it’s much more money-oriented than it used to be. I think it’s very hard for young artists because they’re under a lot of pressure to come with something new and different, but when you have 1,000 kids all trying to come up with something new and different, there’s not that many ideas left. I’m not that into anything technical so I’m the wrong person to talk about it, but there’s digital art. It’s kind of overwhelming, I think, but there’s a lot of good art being made too.

Who’s throwing the best parties these days?

Well, I think Vito, but now Peter Marino in Southampton. There’s this French-Algerian young guy—Lounes Mazouz, who has the ability to become the new Steve Rubell of New York—who’s taken over the old Club 82 that we used to go, which was a drag queen club that evolved into a punk club in the ‘80s and then was defunct. And he just recently opened the restaurant part on the ground level which is on the small side, and the club will be downstairs and it’s huge and it’ll be a combination cabaret and disco. But just since he’s opened the restaurant two weeks ago, every night there’s all these great young people, everybody’s doing something, everybody is either writing, publishing their first novel or is an architect’s intern. It is, I would say, more the jeunesse dorée, but it’s a great mix.

Also, Robin Birley is opening a club in New York but it’s at least a year away, on Madison Avenue and that’ll be more like an Annabelle’s. It’s nice that some nightlife is emerging that’s for everyone in the sense that it’s not gay, it’s not straight, it’s not black, it’s not white, it’s not uptown, it’s not downtown, it’s to bring back that kind of mix that made the ‘70s so special. The ‘70s were the most open decade in American life since, I would say, the Roaring ’20s, and the Roaring ’20s were really when women starting going out, the flappers, the sexual liberation…

Your advice for anyone who’s trying to make it in that scene today?

Keep cool, don’t push, but try to be at the right place at the right time. Remember that making it past the velvet ropes, speaking metaphorically, is the reward for accomplishing something, that’s what you should aim for. Andy always told young people, they’d say, “I want to be a photographer but I don’t have a good camera.” He’d say, “Take pictures with a bad camera.” I think actually today things really are open but nobody’s brought the thing together. I think political correctness, identity politics, all leads to a kind of tribalization, and that’s the opposite of the life you see in my photographs.

I think it’s very amusing that 40 years later, something I didn’t take really that seriously back then, this work is now showing in one of the most prestigious galleries in the world. And my advice is just hang in there, things might happen long after you expect them to happen, good things.

“Bob Colacello: It Just Happened, Photographs 1976-1982” is on view through July 29 at Thaddaeus Ropac, London.

More Trending Stories:

Is Time Travel Real? Here Are 6 Tantalizing Pieces of Evidence From Art History