Pennsylvania’s Longwood Gardens is receiving a transformational gift of 150 masterpieces. But these aren’t your typical works of art—they’re bonsai trees, and they come from Doug Paul’s Kennett Collection, the largest private collection of the botanical art form outside of Asia.

The initial gift includes 50 trees that will come to Longwood over the next two years. Seven specimens are already on view, with the rest part of a longterm bequest that also includes a $1 million endowment for their care.

A significant number of the trees are more than 100 years old, and many have been designated kicho bonsai, or important masterpieces, by Japan’s Nippon Bonsai Association. Others are omono, or “very large” bonsai, measuring an impressive three or four feet tall.

Kennett is also making the entirety of its 1,200 trees available as loans to Longwood, which started its bonsai collection in 1959, with the purchase of 13 trees from Japanese bonsai artist Yuji Yoshimura.

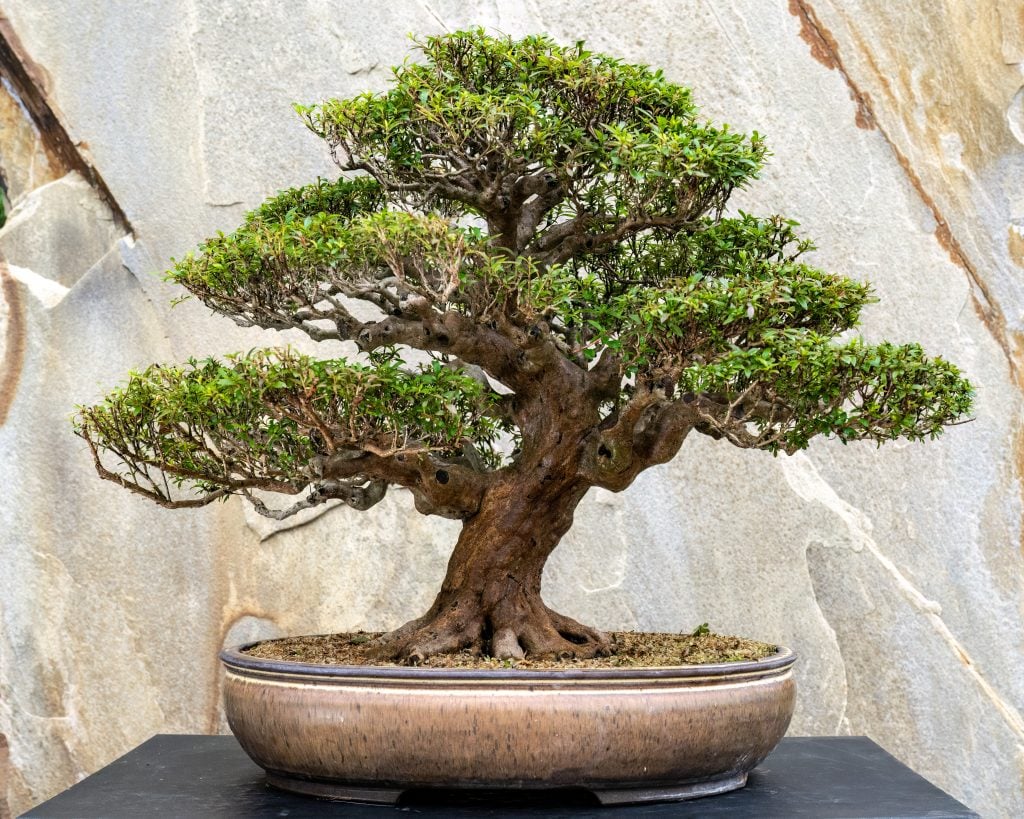

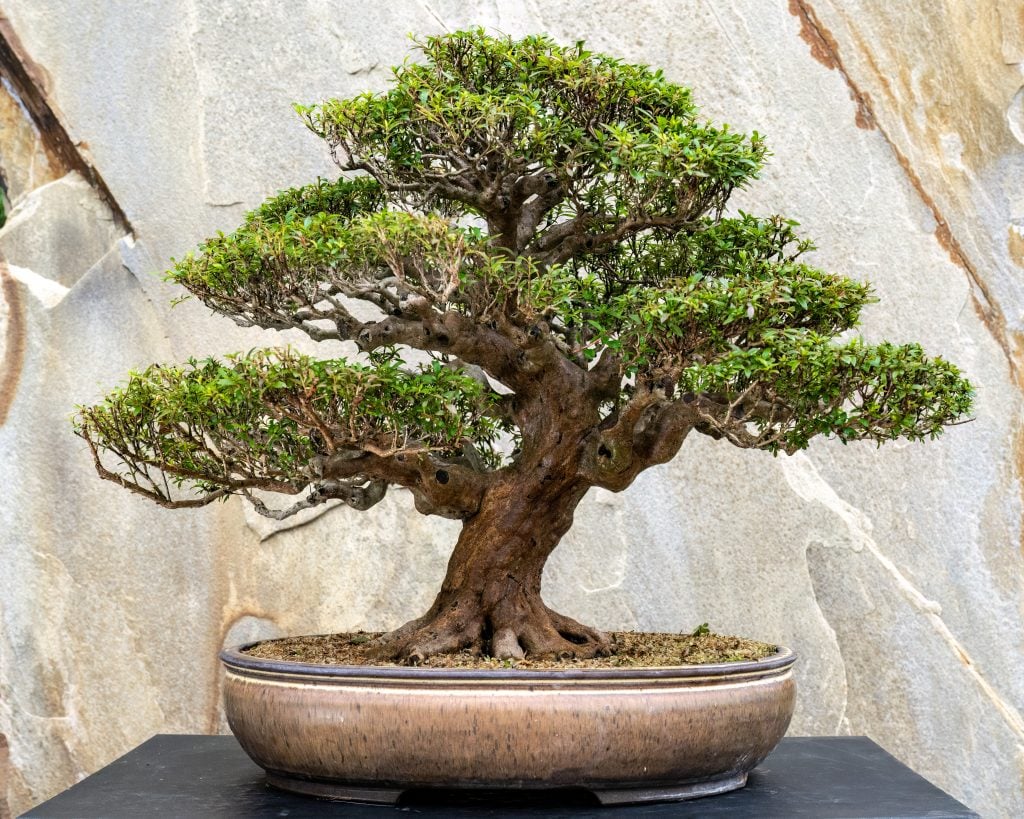

Trident maple (Acer buergerianum) in the root over rock style. Developed by Suthin Sukosolvisit. Photo by Hank Davis, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

A new bonsai courtyard to display the trees will be one of the highlights of the garden’s 17 acres, after a forthcoming revamp titled “Longwood Reimagined: A New Garden Experience,” set to be unveiled in fall 2024.

“This will be our first permanent outdoor bonsai display,” the garden’s bonsai curator, Kevin Bielicki, told Artnet News. “It will be a much more immersive environment, where guests can sit in contemplation and move among the trees, instead of walking right to left, viewing tree by tree.”

To better understand the significance of the Kennett Collection bequest, we spoke with Bielicki about his career, and the complex art of growing and training miniature trees in pots.

A rendering of Longwood Gardens’ planned Bonsai Courtyard. Image: courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

What does this gift mean for the bonsai holdings at Longwood Gardens?

This donation is going to significantly increase the quality as well as the diversity of our collection. Currently, we have about 70 trees, some of which were gifted over time by individual collectors, as well as some acquired from important Japanese masters. We still have four of our original 13 trees, but most of our other trees are of medium quality, from U.S. artists.

This new collection that we’re receiving are all world-class specimens imported directly from Japan. They are going to create a different sense of awe and inspiration in our guests.

How long have you been at Longwood and how did you become a bonsai curator?

In January, I’ll have been here five years. Right out of high school, I started going to a local art college. During my freshman year, one of my art professors asked me if I wanted to do some work on the side for Doug Paul, the owner of the Kennett Collection. I’ve worked there on and off, over the past 18 years, both in a full-time and part-time capacity.

It started out with just general maintenance on the property, such as weeding. Then we were doing a lot of photography of bonsai, so I was setting up backdrops and moving trees for display. Eventually, I moved into working directly on the bonsai themselves.

Most people who train in bonsai go to Japan for roughly five years to study under one master. That’s the usual path. My training was a little bit different. At the Kennett Collection, I was fortunate to learn from many masters from around the world. Doug Paul would fly these individuals out for a day, a week, or even a month at a time, to work on specific specimens, and I had the opportunity to learn from them—it was a very eclectic training in that sense.

Bonsai curator Kevin Bielicki installing trees at Longwood Gardens. Photo: Carol DeGuiseppi, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

When you first encountered the Kennett Collection, what was your gut reaction?

I was just amazed. It was so much to take in. My professor said it was doing some work at a private estate—landscaping and general maintenance. But there was just so much to see and take in when I started working there. Doug Paul has a great attention to detail. All of the tables were handmade and designed for bonsai. There was the koi pond that complimented the trees. It was pretty spectacular.

In terms of the collection’ significance, could you kind of put it into terms that an art reader might understand, such as the Barnes Collection or something like that?

That’s a pretty good comparison! Doug’s appreciation and interest isn’t just in bonsai. Much like Alfred Barnes, he displays his collection in really unique, one-of-a-kind antique Japanese pots or with little figurines and sculptures that are sort of paired with these pieces.

Longwood Gardens bonsai curator Kevin Bielicki. Photo: Phil Bradshaw, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

Why did Longwood Gardens want to expand its bonsai collection?

I think it’s a growing art form, particularly in the U.S., and there’s a high demand from our guests. For many of them, it’s really their favorite thing to see, what they always look forward to. No matter what time of year, there’s always something new to see.

Guests are always amazed by bonsai trees, and they sometimes have trouble wrapping their heads around how these are grown—or even the fact that they’re real! To see a small pomegranate that’s a foot tall with a full-sized fruit on it, it just captures their imagination in a lot of different ways.

What goes into training a plant specimen to become a bonsai tree?

Bonsai itself means “contained tree” or “tree in pot.” So it’s not only the tree, it’s the combination with a pot that creates that overall design, or feel, or mood of the piece.

One of our goals as bonsai artists is to create an aged aesthetic, so it appears to be a mature tree in the landscape. By nature, some bonsai are slower-growing. Some are more vigorous, and you can produce fine branching and a nicely sized trunk much faster. You could have a finished tree in five years—or it could take 100 years.

There are also different ways to start bonsai. You can start it from nursery stock, from seeds or cuttings. There are nurseries that grow them in the field to build up the size and the girth of the trunk before it’s put in a container.

But my favorite way—and the way to achieve results the fastest—is collecting from nature. In the mountains, there are trees that grow exposed to really harsh conditions—wind, snow, stones falling on them, growing between the cracks in rocks. If resources and nutrition are very limited, that creates dwarfs. A tree we collect could be anywhere from 100 to 3,000 years old, depending on the specimen.

And what nature does, it does so much better than what a bonsai artist can. The way it shapes and contorts the tree, and it finds light and finds ways to grow, creates really unique variety and character within the overall line.

Trident maple (Acer buergerianum) in the root over rock style. Developed by Suthin Sukosolvisit. Photo: Hank Davis, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

Can any tree can be a bonsai, or are there some that don’t lend themselves to this contained growth?

There are traditional bonsai trees, but really, any woody material could potentially be trained for bonsai. Anything that has a naturally smaller leaf or smaller flower, lend themself to it a little bit better.

A deciduous tree like a large sugar maple has a rather large leaf and they’re very vigorous. So from a maintenance standpoint, it can be very hard to keep them in shape without constant pruning. And because the leaves are so large, you don’t really get to enjoy the structure—you see the leaf mass. However, a tree like that out of leaf will have a really beautiful winter silhouette you could show.

Whether you’re collecting a specimen from nature, or if you’re starting from scratch with a seedling or cutting, walk me through kind of the cultivation and art of creating a bonsai tree. What are the steps?

I think the most important thing is to know what your goal is, what you’re trying to achieve, and that can inform the process overall.

In the Japanese aesthetic, there’s a more feminine style, or there’s a masculine style. The feminine has longer, slender trunks, a more elegant form, and the masculine is more massive trunks.

If we want to develop a massive masculine tree, with a really nice symmetrical form, we would first start developing the trunk. If we’re starting from a seedling, we might keep it in a container for a couple years to let it get strong and vigorous. And then over time, we may transfer that into the ground, and grow it in a field.

That could take five or 10 years depending on the species. In the ground, we increase the thickness of the trunk, and also create the nebari, the Japanese term for exposed roots. That’s what really gives you that sense of the tree gripping and grasping the ground.

Transferring from a field to a bonsai container with bonsai soil takes a couple years. We grow in a really coarse medium that’s almost more like hydroponic growing, where you’re growing without soil, to achieve a really good air/water balance.

Next, we’re focusing on starting to develop our primary branching. As we prune the tree, we see where adventitious buds or new growth sprout from, and we utilize that and we direct that growth. We also use wire to shape the branches and give them directionality. And scale and proportion are so important for creating that miniature look. We’ll prune them at specific times of the year, such as early spring, when buds are just emerging, which causes the next blush of foliage or growth to come out much smaller in size.

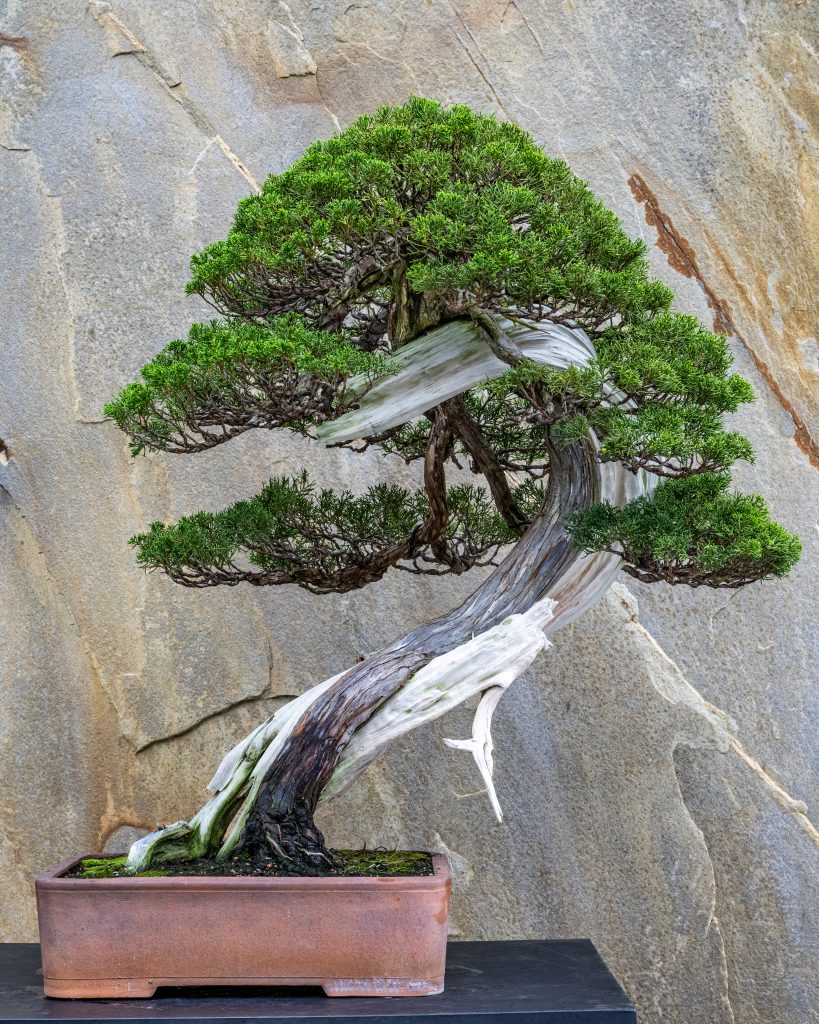

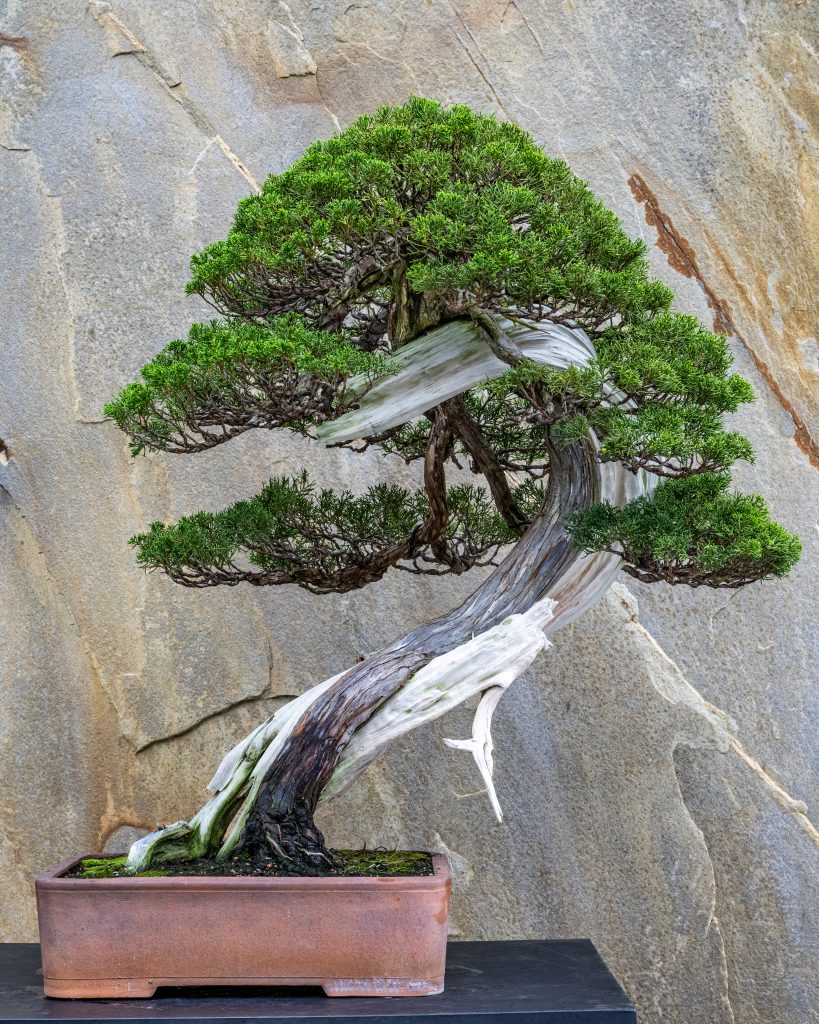

Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis ‘Shimpaku’) in the slant style. Developed by Seiji Morimae. Photo by Hank Davis, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

If it takes a few years to transfer a tree from the field to a pot, is that because you’re kind of slowly transitioning the type of soil that it’s in?

Yes. When we repot, it’s almost like open heart surgery on the tree—it can be a very stressful process. If we remove all of the soil at once, it removes a lot of this really good microbial activity and nutrition that’s been acquired over time. That can weaken the tree. So by taking smaller sections over time, over the course of multiple repottings, that helps maintain the health of the tree.

And when we repot, that’s always time to go in and prune the roots, just like we prune our branches. That’s what really keeps it growing happy and healthy in the containerized environment.

Normally, a plant would become root bound if you kept it in a small pot for too long. Are you basically just constantly tending to the roots to make sure that doesn’t happen?

Exactly. But having a tree be root bound can actually work to our advantage as artists too. With a tree that’s mature, it has really beautiful branches—what we would call a finished tree, if there were such a thing. We’re trying to slow down the growth habit at that time. We’ll decrease watering and fertilizing. Allowing the tree to go root bound can further slow down that process and produce smaller and finer internodes. So it’s all about what stage and development we’re in and what we’re trying to achieve.

Cork Bark Japanese Black Pine (Pinus thunbergii) in the slant style. Developed by Chinsho-en nursery in Takamatsu, Japan. Photo: Hank Davis, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

How many trees can a bonsai artist be training at any given time?

At Longwood, we have maybe 20 or 30 trees that are in training, and they may be ready in anywhere between five to 10 years. We’re always looking to refine our trees and development, so if we have 20 that we really like, but we’re able to acquire another one, we might cycle out one that’s not as good.

Among the seven Kennett Collection trees now on view at Longwood, is there one that you’re particularly excited about?

There is a beautiful white pine root over rock tree by Kimura Masahiko, who is a famous Japanese bonsai master. He’s like, the Michael Jordan of bonsai, and he’s known as “The Magician.” So he’s like almost like a Picasso, or Cézanne. He revolutionized so many of the techniques and really made bonsai what it is today.

I also really enjoy working the cork bark black pine. It’s a really interesting specimen because it’s actually a fungus that causes the bark to form the really gnarly texture that works so well for bonsai. It gives this ancient looking vibe to the trunk. It’s perfect.

Japanese white pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’) in the slant style. Developed by Kimura Masahiko. Photo: Hank Davis, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

When you have roots growing over a rock, is that because when you repot it, instead of burying the roots back in the ground, you make the decision to leave them exposed?

Exactly. It becomes part of the aesthetic, as if it’s a tree growing on the edge, where the roots are just trying to grapple on, or a tree near a waterway, where erosion is continuously happening, exposing the root system.

It’s part of the whole training process. Many times when a tree’s developed that way, it’s grown in long slender tubes versus a wide container. That causes an elongation of the roots. And year by year, the pot is lowered, revealing the roots. That thickens and hardens them, making them durable.

For you, how does bonsai compare to the more traditional fine arts of sculpture and painting?

It’s very similar, but it can also be different. We use a lot of the traditional principles and elements of design—line, form, texture, rhythm, and things like that. But what makes it really unique is that bonsai is one of the few art forms that is really about time. It’s a responsive art form. It’s a give and take. We prune the tree, we see how it responds. We’re always working in response to the tree.

Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii) in the upright style. Developed by Suzuki Shinji. Photo: Hank Davis, courtesy of Longwood Gardens.

And unlike with restoration and conservation of a painting or sculpture, tending to a bonsai tree, as a living thing, is a constant demand.

Yes, the trees are always changing. Every year, they’re pruned to maintain their overall look. Sometimes, just like trees in nature, a branch dies unexpectedly and that requires a redesign. Branches have to be rewired, repositioned to rebalance the form.

What are the main things that might endanger the health of a bonsai?

Watering is the biggest thing to master, and also the most important thing for making the tree strong and resilient. Each species has its different tolerances. Knowing what is the correct soil to use with each tree and how often to water it depending on the time of year, when it’s been pruned, the atmosphere, if it recently rained…

If we can maintain a healthy tree through watering, it will have natural resilience to pests and disease. Deciduous trees can be a little prone to fungal issues. Sometimes scale or aphids can make their way into some of our species, but we have a regular IPM or integrated pest management routine.

The ever-changing climate is a major challenge as well. I was just out in Seattle and they had some extremely hot weather that impacted bonsai health. You have to adapt and change locations of trees when they are on display outside.

“Longwood Reimagined: A New Garden Experience” will open at Longwood Gardens, 1001 Longwood Road, Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, in fall 2024. The first seven bonsai trees donated by the Kennett Collection are on view October 4–November 13, 2022.

More Trending Stories:

Jameson Green Won’t Apologize for His Confrontational Paintings. Collectors Love Him for It

Are You Sitting Down? A Ming Dynasty Chair Just Sold for $16 Million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong—Nearly 10 Times Its Estimate

For Its 30th Anniversary Gala, Robert Wilson’s Fabled Watermill Center Borrowed a Theme from H.G. Wells and Took a ‘Stand’

‘The More You Shut Up, the Better’: Painter Adrian Ghenie on Giving Up Trying to Control His Frankenstein’s Monster of an Art Market

Robot Artist Ai-Da Just Addressed U.K. Parliament About the Future of A.I. and ‘Terrified’ the House of Lords